"The Myth of Straight Photography: Sharp Focus as a Universal Language," FK Magazine, January 18, 2018. Download the article as pdf.

“Although it is always interesting to get the photographer’s point of view, I believe that pictures actually require little explanation. The photographic image speaks directly to the mind and transcends the barriers of language and nationality,” in 1957 claimed American photographer and journalist Arthur Rothstein (1915–1985).

That photography is a language, and a universal one at that, was a popular metaphor in the 1950s. Such a language, as photographers and politicians claimed, could finally unite all people of the world because it transcends languages, cultures, religions, political positions, and any other differences. Although today such a belief in the power of photography can seem naïve, in the decade following the end of the Second World War it expressed a hope for a better—peaceful—future.

But not just any kind of photography was believed to be a universal language. When Rothstein and many others in the 1950s were talking about photography as a universal language, they arguably had “straight,” documentary photography on their mind. But exactly what kind of photography is “straight,” and why it was supposed to be so universal?

To find out, we have to look back to the pictorialist movement of the early twentieth century, the shift of aesthetic preferences around 1916, the American historiography of photography, and all kinds of postwar "non-straight" photography that it has excluded .

As its mainstream understanding goes since the 1950s, photography’s sole aim is to create “straight,” realistic, documentary depictions of the visible world. This function of photography has been internalized by historians, theorists, and museum curators worldwide, and their preferences have marginalized all other kinds of non-straight photographic practices—including the Brazilian Concrete photography and West German Subjektive Fotografie.

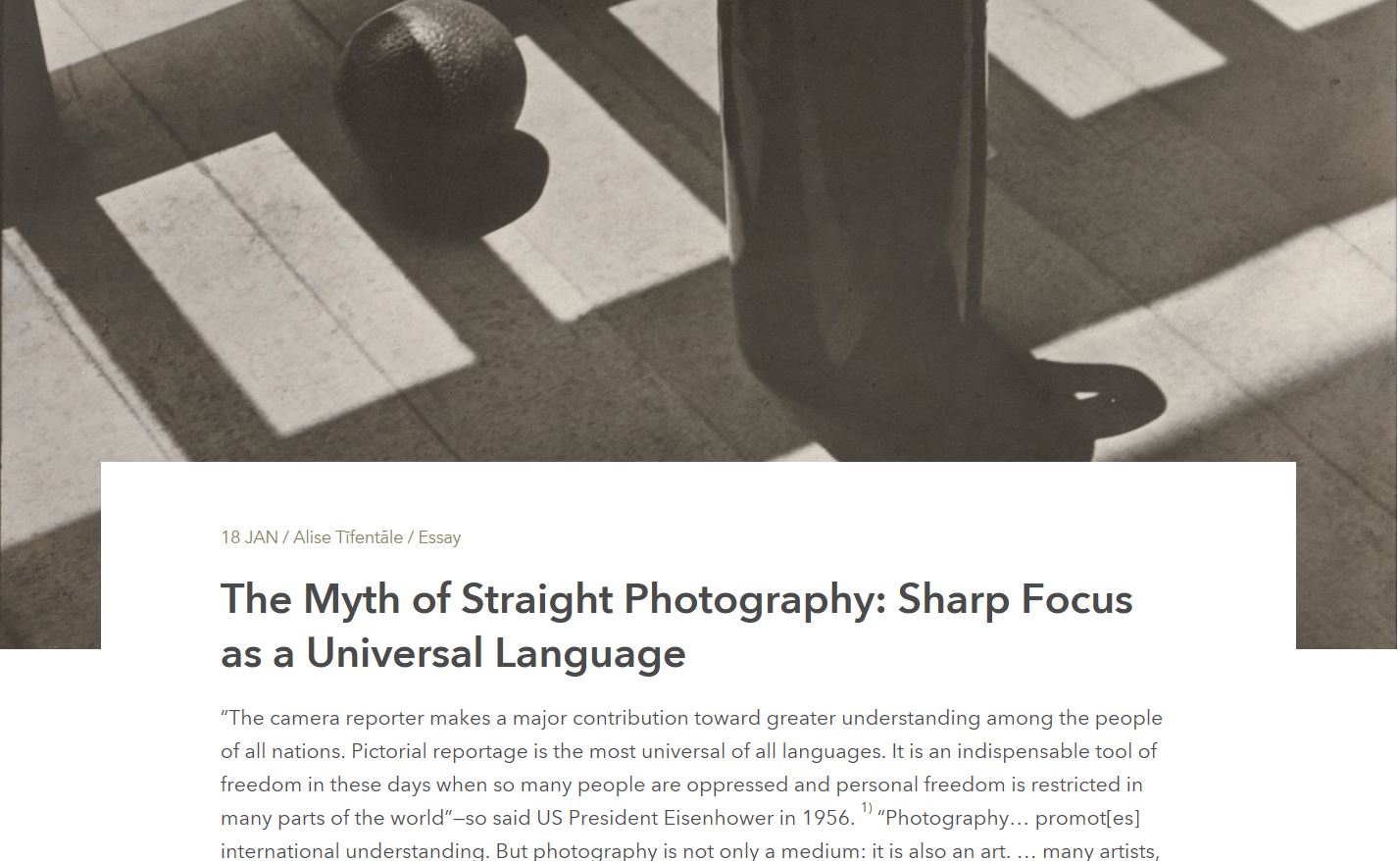

José Oiticica Filho (Brazilian, 1906–1964). Untitled, undated (1950s). Oiticica Filho's work exemplifies Brazilian Concrete photography.

Read the full article for free on FK Magazine!