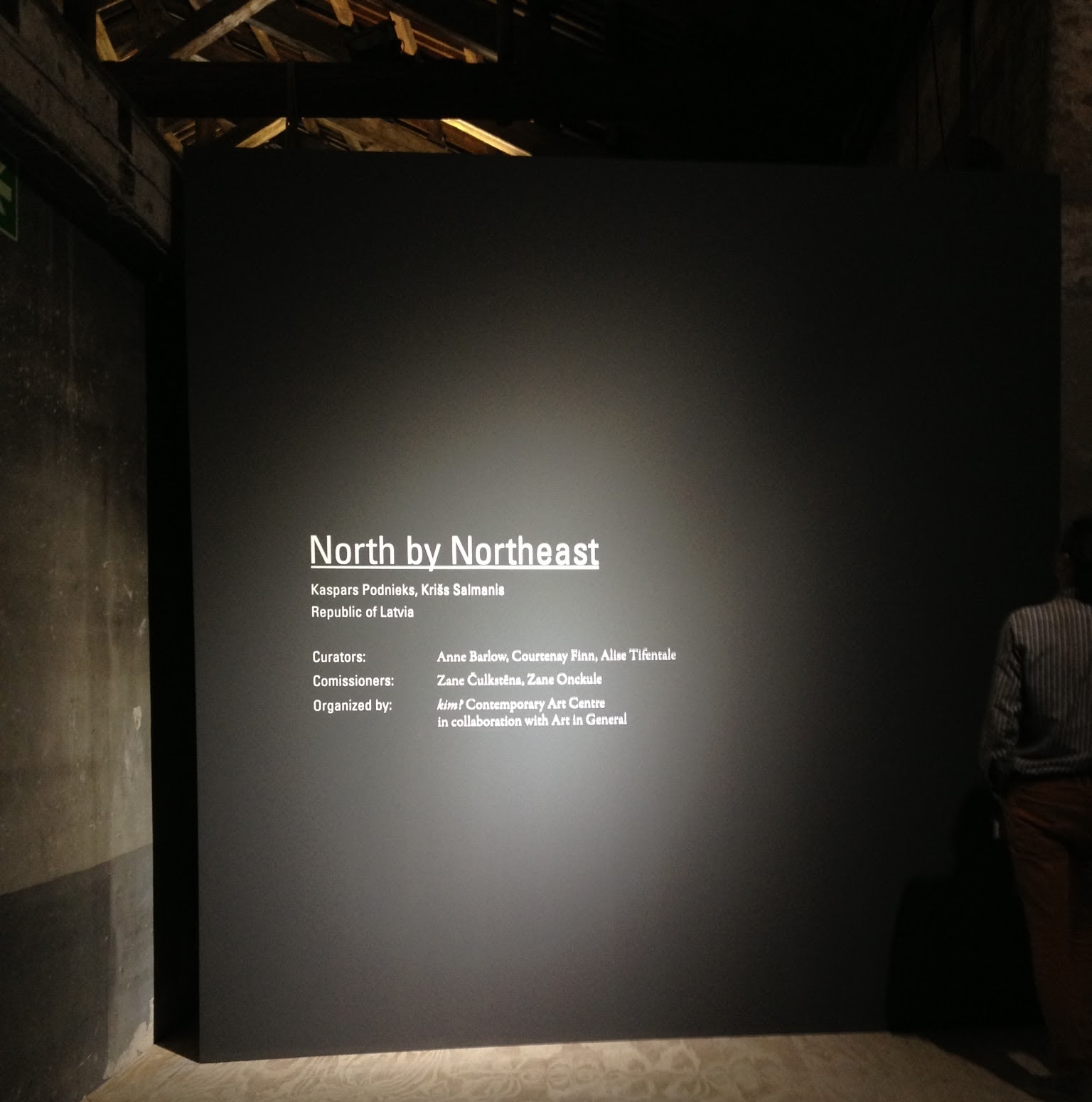

This is my introduction to North by Northeast, the Latvian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, co-curated by Anne Barlow, Courtenay Finn, and me.

North by Northeast in this Venice Biennale presents new works by two Latvian artists, Kaspars Podnieks and Krišs Salmanis. Both works can be misleading in their seemingly one-liner appearance. An upside-down tree and a series of black-and-white photographic portraits of farmers – is this a simple case of what you see is what you get? I would like to argue that it is rather the opposite – you are supposed to get what you actually do not see.

Latvian contemporary art is essentially a misunderstanding, an exception, or possibly a miracle. There is no tangible economic basis for the luxurious superstructure in this economically troubled country without a tradition of private funding for the arts. The audience for contemporary art is very limited, consisting of a tiny, economically, socially, and politically rather disenfranchised community of artists, art critics, and their families and friends. Besides, the long history of Soviet rule in Latvia developed a strong antipathy towards politically or socially explicit art. With a backdrop of highly politicized mass communication and visual culture, and ideologically charged official art, anything apolitical was seen as an escape, as a source of pleasure, sometimes even as a form of resistance. Speaking and reading between the lines was the major rhetorical strategy adapted by almost all social strata, equally employed in casual everyday conversations as well as in visual art, poetry, literature, and theater. The legacy of these generations is still very much present, therefore one should not expect a Latvian contemporary artist to be openly Marxist, anarchist, or any other sort of social revolutionary. What then should one expect? This essay attempts to articulate some possible answers.