Review of the exhibition Public Eye: 175 Years of Sharing Photography at the New York Public Library, Stephen A. Schwarzman Building from December 12, 2014 to January 3, 2016. Published in Studija 100, no.1 (2015): 72-77.

Read moreThe Impossibility of Capturing Butoh in Photography

“Neiespējamais butō tulkojums fotogrāfijā [The Impossibility of Capturing Butoh in Photography],” in Simona Orinska, ed., Butoh (Riga: Mansards, 2015), 68-79. In Latvian only. ISBN 9789934121098. Available from the publisher's website.

I’m grateful to Simona Orinska, the editor of this book and a butoh artist, for inviting me to contribute to this volume and to think about such a challenging topic.

Since 2011, when Orinska conceived the idea of the book and solicited the first drafts of the articles, I’ve had many chances to return to the topic and ask myself, how can I describe the relationships between butoh, a performance based on movement and emotion, and photography, a medium that freezes movement and removes all emotions?

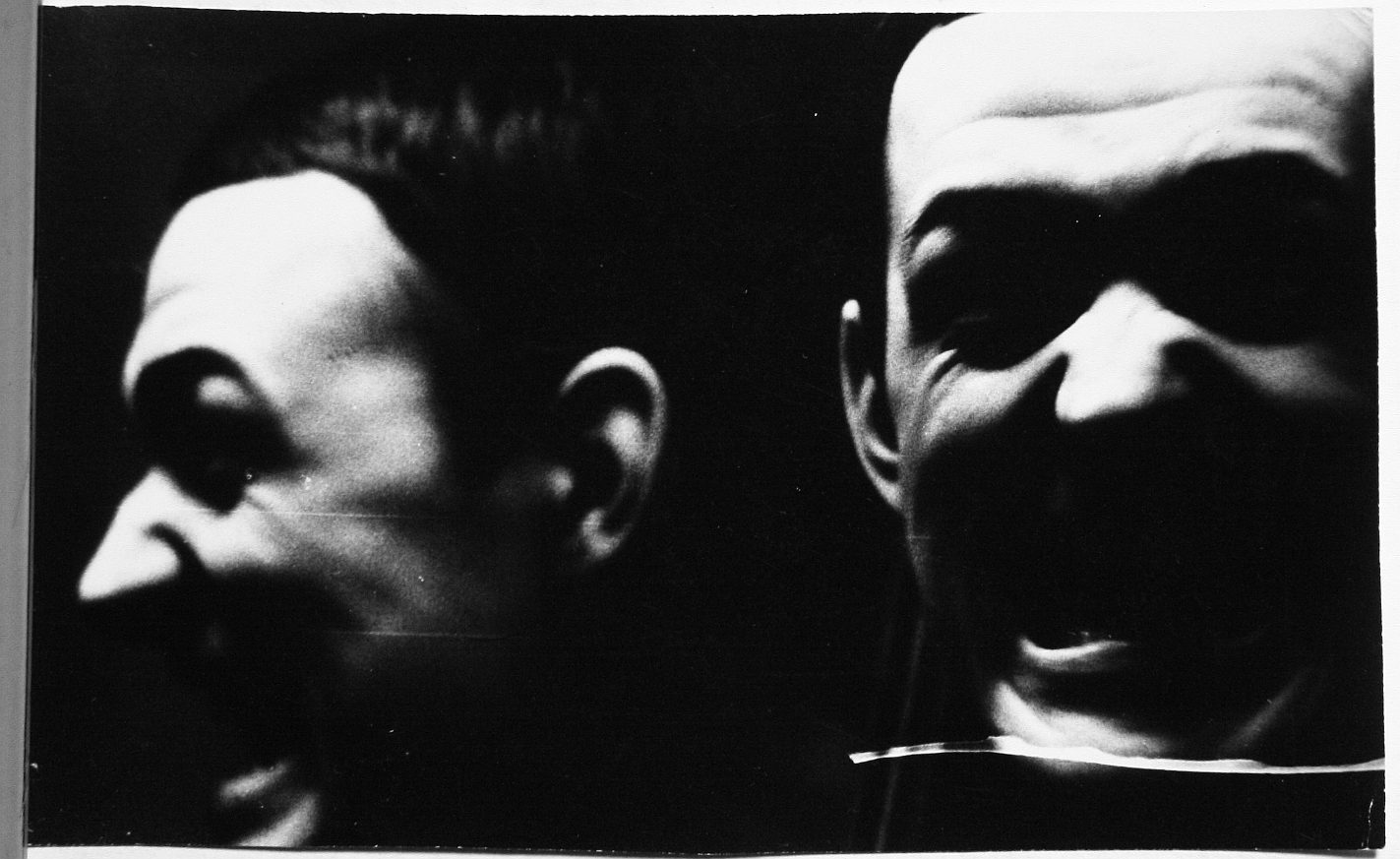

To address this question, in this article I revisit theoretical writings about the depiction of movement and dance in photography. I introduce a comparative reading of Kamaitachi (1968), a well-known series of photographs by Japanese photographer, Eikoh Hosoe (b. 1933), and Riga Pantomime (1964-1965), an almost unknown series by Latvian photographer and artist, Zenta Dzividzinska (1944-2011).

This comparison brings to the fore a similarly heightened expressiveness of human body and face that photographers captured in two different cultures: in butoh of the postwar Japan and pantomime in Latvia under the oppressive Soviet regime. Can there be two more different cultures as these? But a totally unexpected meeting point of these cultures appears in a photograph by Zenta Dzividzinska, Hiroshima (1964-1965), taken at a rehearsal of eponymous performance by pantomime troupe Riga Pantomime.

See below more photographs by Zenta Dzividzinska from the series Riga Pantomime (1964-1965). Most of the photographs from this series were never exhibited during the artist's lifetime, but a small selection of vintage prints recently was included in the exhibition Society Acts (September 20, 2014 - January 25, 2015) at the Moderna Museet, Malmö, Sweden. Read more about this exhibition and my short presentation of Dzividzinska's works at the Moderna Museet.

Steichen, The Artist and Propagandist

"The Artist and Propagandist: Steichen's Role at Two Decisive Moments in the History of American Photography," in Šelda Puķīte, ed., Edward Steichen. Photography (Riga: Latvian National Museum of Art, 2015), 33-37. ISBN 9789934512575. Published on the occasion of exhibition "Edward Steichen. Photography" at the Latvian National Museum of Art, The Arsenals Exhibition Hall, Riga, Latvia, June 26 – September 6, 2015.

Edward Steichen’s name is associated with the emergence of two aesthetically and thematically different and even oppositely oriented movements in photography. At the beginning of the 20th century Steichen was a pioneer of Pictorialism, and his 1904 photograph The Pond-Moonlight is a textbook example of this artistic style: intimate, romantic, timeless, and painterly.

Yet in the middle of the 20th century Steichen became a master of American political propaganda in photography and remains known for the creation of a radically new and different type of photography exhibition. In Steichen’s curated photography exhibitions, Road to Victory (1942) and The Family of Man (1955) at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, photographs lost their individuality, and the participating photographers’ original intentions were sacrificed for the sake of creating an atmosphere of patriotic pathos.

This article examines “Steichen the Pictorialist” and “Steichen the Curator,” the two contradictory directions in Steichen’s career and their interpretations by art historians in order to establish a broader context for the work on view in the current exhibition.

Selfiecity: Exploring Photography and Self-Fashioning in Social Media

“Selfiecity: Exploring Photography and Self-Fashioning in Social Media” (co-author Lev Manovich), in David M. Berry and Michael Dieter, eds., Postdigital Aesthetics: Art, Computation and Design (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 109-122. ISBN 9781137437198.

NB: This is unedited working draft. Please refer to the book for the final published version of this chapter.

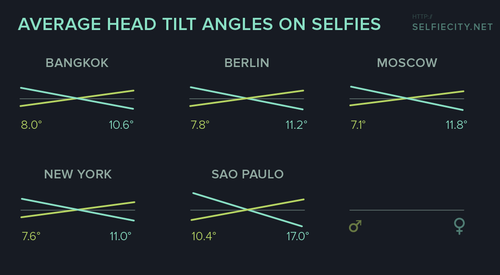

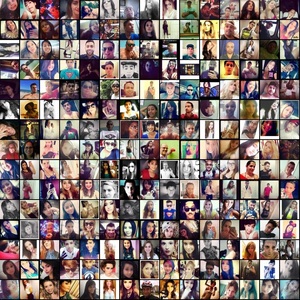

This chapter summarizes the methods and findings of the research project Selfiecity (2014).

User-generated visual media such as images and video shared on Instagram, YouTube, and Flickr open up fascinating opportunities for the study of digital visual culture and thinking about the postdigital. Since 2012, the research lab led by Lev Manovich (Software Studies Initiative, softwarestudies.com) has used computational and data visualization methods to analyze large numbers of Instagram photos. In our first project Phototrails, we analyzed and visualized 2.3 million Instagram photos shared by hundreds of thousands of people in 13 global cities.

Given that everybody is using the same Instagram app, with the same set of filters and image correction controls, and even the same image square size, and that users can learn from each other what kinds of subjects get most attention, how much variance between the cities do we find? Are networked apps such as Instagram creating a new universal visual language which erases local specifities? Does the ease of capturing, editing and sharing photos lead to more aesthetic diversity? Or does it, instead, lead to more repetition, uniformity and visual social mimicry, as food, cats, selfies, and other popular subjects drown everything else out?

In our project we wanted to show that no single interpetation of the selfie phenomenon is correct by itself. Instead, we wanted to reveal some of the inherent complexities of understanding the selfie – both as a product of the advancement of digital image making and online image sharing and a social phenomenon that can serve many functions (individual self-expression, communication, etc.).

By analyzing a large sample of selfies taken in specified geographical locations during the same time period, we argue that we can see beyond the individual agendas and outliers (such as the notorious celebrity selfies) and instead notice larger patterns, which sometimes contradict popular assumptions.

For example, considering all the media attention selfie has received since late 2013, it can easily be assumed that selfies must make up a significant part of images shared on Instagram. Paradoxically enough, our research revealed that only approximately four percent of all photographs posted on Instagram during one week were single person selfies.

Art of the Masses: From Kodak Brownie to Instagram

“Art of the Masses: From Kodak Brownie to Instagram,” Networking Knowledge 8, No. 6 (2015). Special issue “Be Your Selfie: Identity, Aesthetics and Power in Digital Self-Representation,” edited by Laura Busetta and Valerio Coladonato.

Read moreMaking Sense of the Selfie: Digital Image-Making and Image-Sharing in Social Media

“Making Sense of the Selfie: Digital Image-Making and Image-Sharing in Social Media,” Scriptus Manet 1, No. 1 (2015): 47–59. ISSN: 2256-0564.

The article addresses digital photographic self-portraiture in social media (so-called selfies) as an emerging sub-genre of amateur photography. The article is a result of my involvement in the research project Selfiecity (2013-2014), based on the analysis of 3,200 selfies shared on Instagram from five global cities: Bangkok, Berlin, Moscow, New York, and Sao Paulo. This research project was conducted by Software Studies Initiative, a research lab led by Dr. Lev Manovich and based in the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. In this research project, the lab used computational and data visualization methods to analyze large numbers of photographs shared on Instagram. In this article, I situate the selfie in the context of history of photography and seek to inscribe this sub-genre in a broader genealogy of photographic self-portraiture.