"Fifty Year Eclipse: Illuminating the Forgotten Legacy of Photographer Vilis Rīdzenieks."

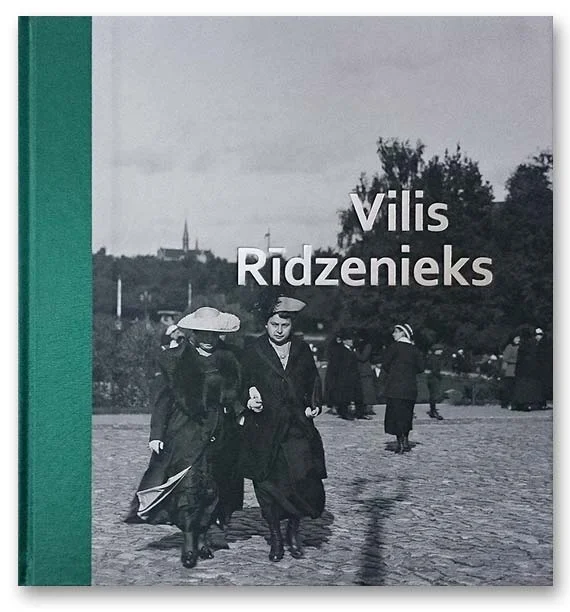

Book chapter commissioned for an edited volume dedicated to the legacy of Latvian photographer Vilis Rīdzenieks (1884–1962).

Book info: Vilis Rīdzenieks. Edited by Katrīna Teivāne-Korpa. Riga: Neputns, 2018. In English and Latvian. ISBN 9789934565564

Read the article—download a pdf here.

More info about the book and ordering options: see the publisher’s website.

A few more sample spreads from the book are here.

Photo: Katrīna Teivāne-Korpa. 2019.

Alise Tifentale, "Fifty Year Eclipse: Illuminating the Forgotten Legacy of Photographer Vilis Rīdzenieks" in Vilis Rīdzenieks, ed. Katrīna Teivāne-Korpa (Riga: Neputns, 2018).

Download a pdf or preview an excerpt below.

Vilis Rīdzenieks. Untitled. 1912.

It is Wednesday, April 17, 1912. Partial solar eclipse has attracted onlookers to gather in city streets throughout Europe and observe the unusual celestial event through pieces of smoked glass. Latvian photographer Vilis Rīdzenieks (1884–1962) is out in the streets of Ventspils, an important sea port city on the Baltic Sea coast of the present-day Latvia, then the Governorate of Kurland, part of the Russian Empire. Among else, Rīdzenieks captures a group of five men and two boys standing on a cobbled plaza and looking upward, toward the upper right corner of the frame. All are holding small pieces of glass in front of their faces. Their identical gestures, the long, sharp shadows they cast behind them, and the absence of the subject of their interest all create an eerie atmosphere.

Eugène Atget. Eclipse. 1912.

The same solar eclipse is visible also in France. On the same day, around the same time, French photographer Eugène Atget (1857–1927) is out in the streets of Paris, the capital city of modern art. Among else, Atget captures a group of women, men, and a few children standing on a side of Place de la Bastille and looking upward, toward the upper left corner of the frame (figure 2). All are holding small pieces of glass in front of their faces. Their identical gestures, the repetitive advertising on the building behind them, and the absence of the subject of their interest all create an eerie atmosphere.

Fred Espenak, World Atlas of Solar Eclipse Paths. Eclipse Predictions by Fred Espenak, NASA's GSFC (2008), https://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEatlas/SEatlas.html

From here onward, we could embark on a success story of two early-twentieth-century photographers whose work has been recognized and appreciated by the art and photography historians. Yet it is not the case. Ventspils and Paris offered quite different treatment to these two equally talented photographers working in the two cities. It happened so that one of Atget’s neighbors in Paris was Man Ray (1890–1976), the notable American avant-garde artist and photographer. In 1923, Ray purchased the solar eclipse photograph from Atget, and the image was reproduced on the June 15, 1926 cover of La Révolution Surréaliste, one of the most artistically radical publications of its time.[i] After Atget’s death the following year, another American photographer, Berenice Abbott (1898–1991) purchased what was left of his legacy—more than 1,000 glass negatives and more than 7,000 prints, and brought it back to the U.S. The collection of Atget’s work ended up in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, arguably one of the world’s most powerful institutions shaping the mainstream histories of art and photography. Atget’s work since then has been praised, admired, and firmly established as one of the most important sources of modern photography.

Ventspils, or Rīdzenieks’ later hometown Riga, meanwhile, did not offer such a springboard for the recognition of a photographer’s work. No avant-garde artist was nearby to see and appreciate Rīdzenieks’ images, no notable collector purchased his works, and no powerful institution such as MoMA was around to popularize his legacy. No doubt, after his passing in 1962, Rīdzenieks’ name has been generally known among photography enthusiasts in Latvia, he has been mentioned in a few books and articles, and few random samples of his work have been reproduced here and there. But his diverse output has never been acknowledged, exhibited, and discussed in its entirety. Instead of being studied and venerated as the classic of Latvian photography, most of his images were quietly set aside and remained outside the public view until now. His legacy has been totally eclipsed for the duration of the second half of the twentieth century.

In 2018, when we celebrate the centenary of Latvia’s independence, we recognize the significance of Rīdzenieks as the author of the only photograph that documents the Proclamation of Independence of Latvia by the People's Council on November 18, 1918 in Riga. For this accomplishment, he was awarded and highly respected throughout the years of the first Republic (1918–1940). These years also were the most prolific period in the photographer’s career. But after the establishment of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Latvia in 1944, which lasted until 1991, visual evidence of the independent Latvia had to be erased from public spaces. Exhibiting or reproducing photographs that documented life in the 1920s and 1930s could be interpreted as praising the achievements of the now condemned “bourgeois” republic and criminalized as anti-Soviet propaganda. A small and careful selection of Rīdzenieks’ work was exhibited posthumously, in 1965. A soft-cover, miniature thirty-page catalogue featuring sixteen reproductions accompanied this exhibition.[ii] This remained the single most substantial publication about Rīdzenieks until 2008 when his unique Proclamation of Independence photograph was commemorated in a book.[iii]

Rīdzenieks, however, did much more than make that one photograph. His life and career spans multiple political regimes ruling the territory of present-day Latvia, two major social and political revolutions, and two world wars. Rīdzenieks has left a rich legacy which remains unexplored and full of surprises. This essay will outline the main genres and thematic groups in Rīdzenieks’ diverse oeuvre and place it on the world map.

[i] David Campany, “Eugène Atget’s Intelligent Documents,” Atget: Photographe de Paris (Errata Editions, 2009).

[ii] Viļa Rīdzenieka piemiņas izstāde. Rīga: Rīgas fotoamatieru klubs pie Poligrāfiķu Centrālā kluba, 1965.

[iii] Laima Slava, ed. First of the State: Vilis Rīdzenieks. The Proclamation of the Latvian State. 18 November 1918 (Riga: Neputns, 2008).

Photo: Katrīna Teivāne-Korpa. 2019.

Photo: Katrīna Teivāne-Korpa. 2019.

Photo: Katrīna Teivāne-Korpa. 2019.

Photo: Katrīna Teivāne-Korpa. 2019.