Summary of my talk:

Instagram—an online platform designed for sharing photographs taken with a smartphone—exemplifies what philosopher Vilém Flusser calls “the universe of technical images.” The main question that I will address today is—how to study this universe?

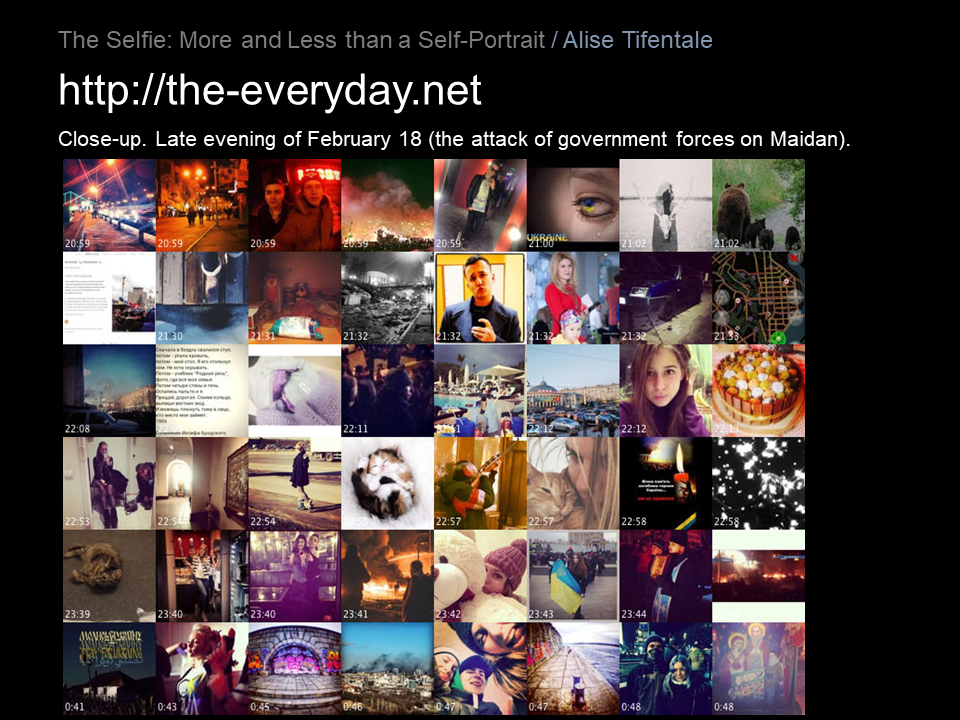

First, in order to fully grasp the visual culture that has emerged in the universe of Instagram since its first release in October 2010, we need to unpack the work of the networked camera. It is not just a new kind of camera. The networked camera is a hybrid tool that seamlessly merges making, editing, sharing, and viewing of images. It comprises hardware and software, the availability of wireless Internet connection, and the existence of online image-sharing platforms such as Instagram. It produces not only images, but also layers of metadata, and establishes connections and relationships. The networked camera has created new conditions for making and viewing photography, and our task is to come up with new methods of studying it.

Instagram is a product of the networked camera, this hybrid device, where making and sharing of images is inseparable from their viewing. All stages of photographic production, distribution, and reception take place seamlessly within the same user interface. Which is significantly different from all earlier photographic practices where these three stages were distinct and separate.

From an art-historical perspective, there is no such thing as Instagram. Because each user’s experience of Instagram photography is unique— every person’s Instagram feed is different. The live feed of images consists of contributions by those other Instagram users that this person is following. If we want to consider the ways in which regular Instagram users produce and consume photography within this platform, we, art historians, are left quite confused. We cannot study Instagram photography the same way we are trained to study, let’s say, photographs exhibited in museums and galleries, kept in archives and personal albums, or reproduced in photo-books and magazines.

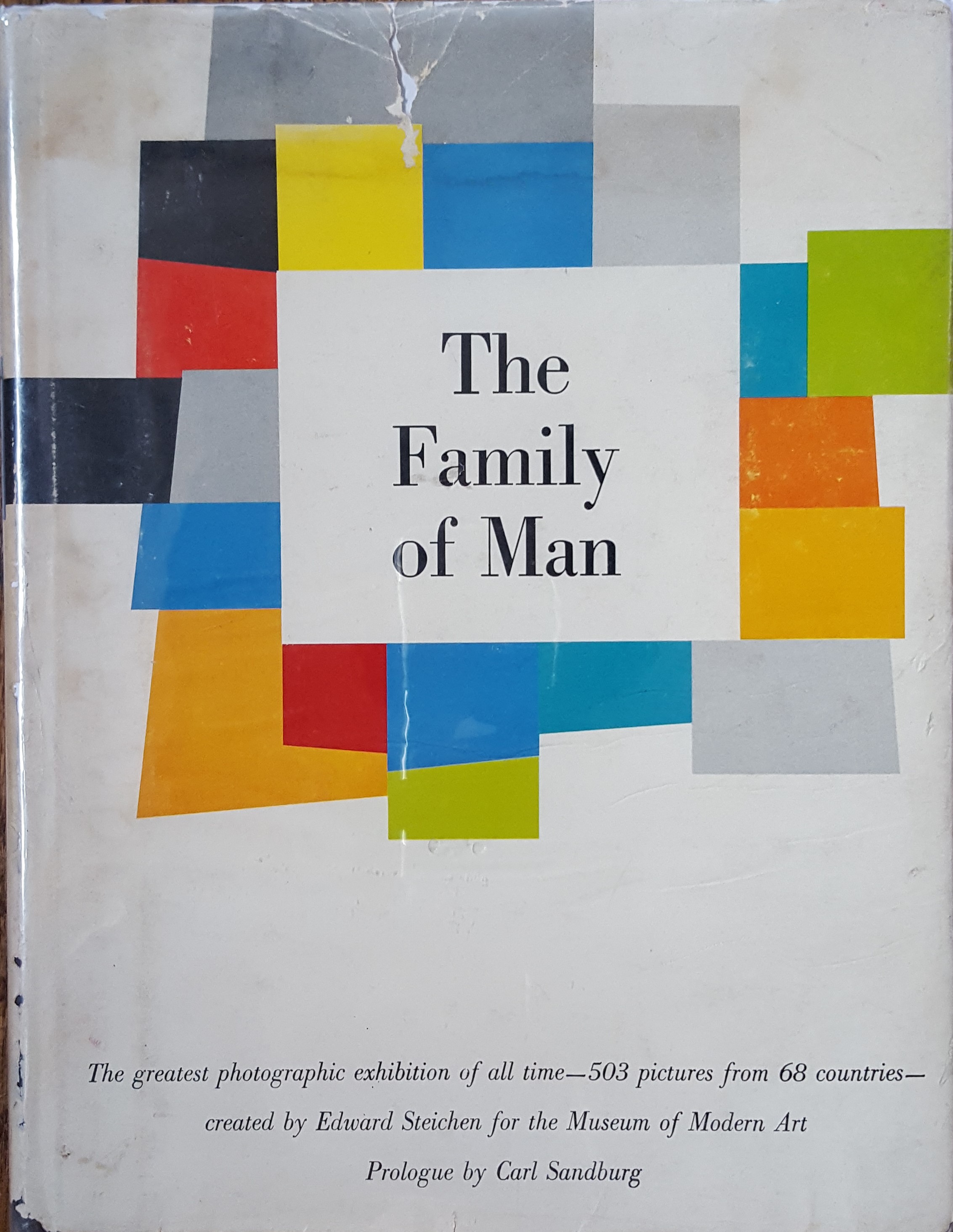

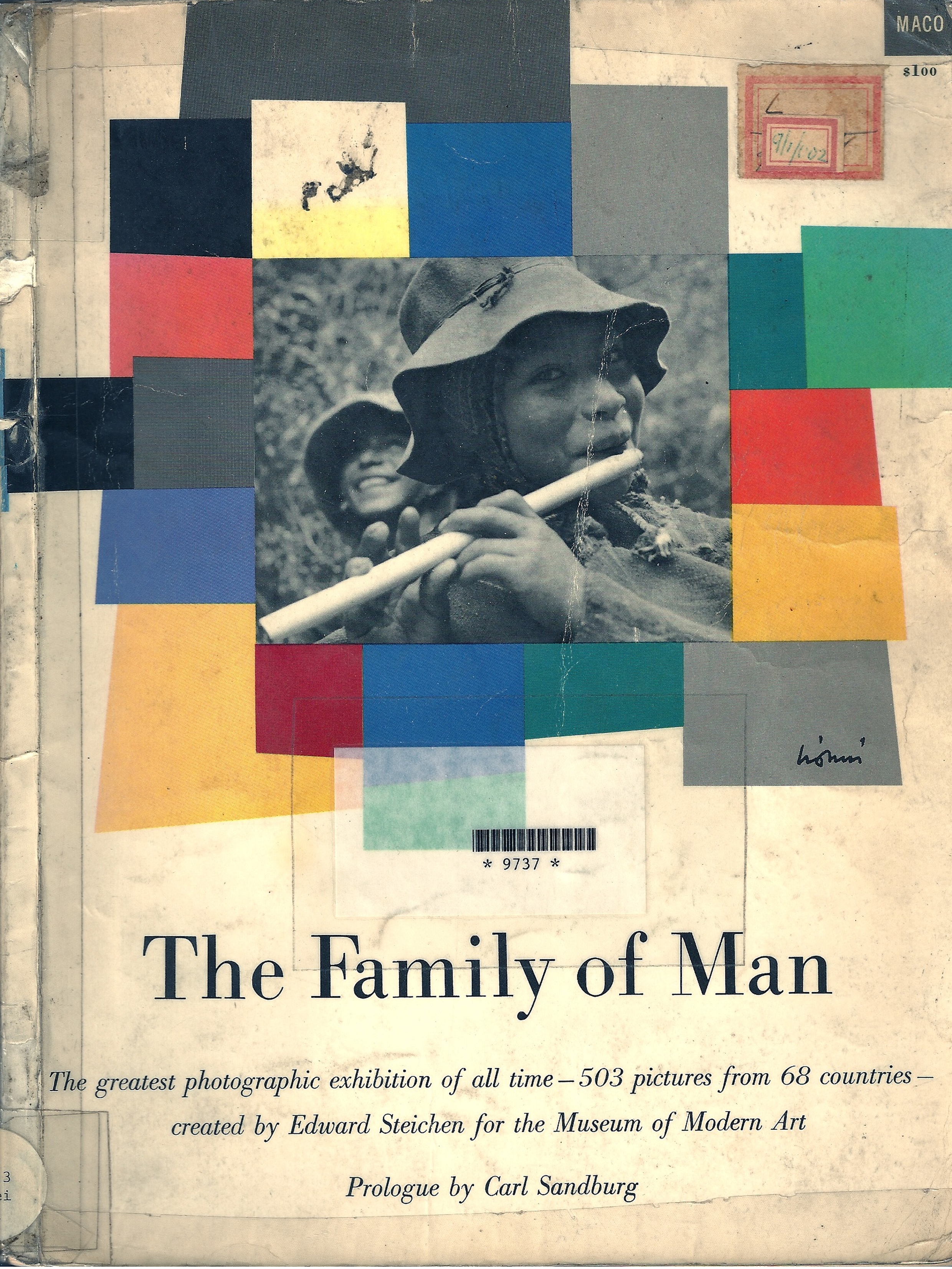

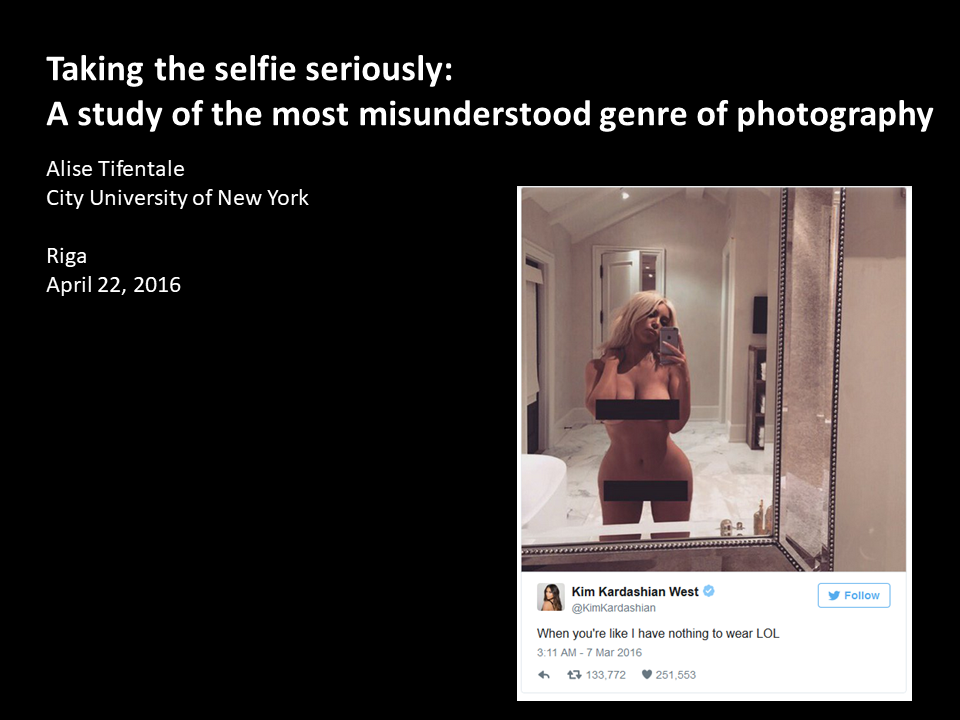

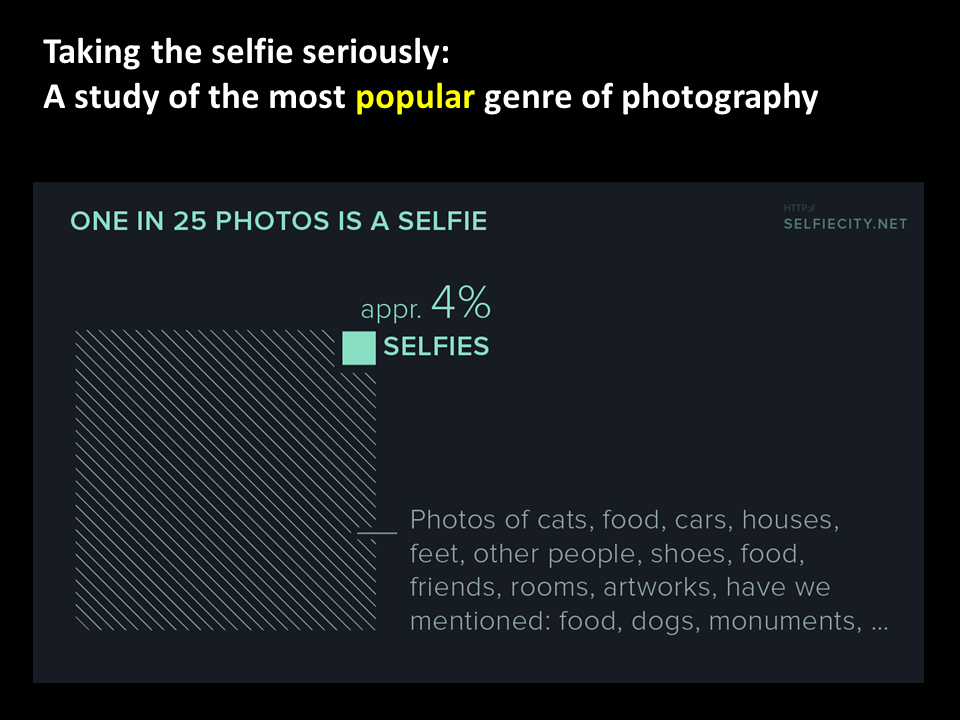

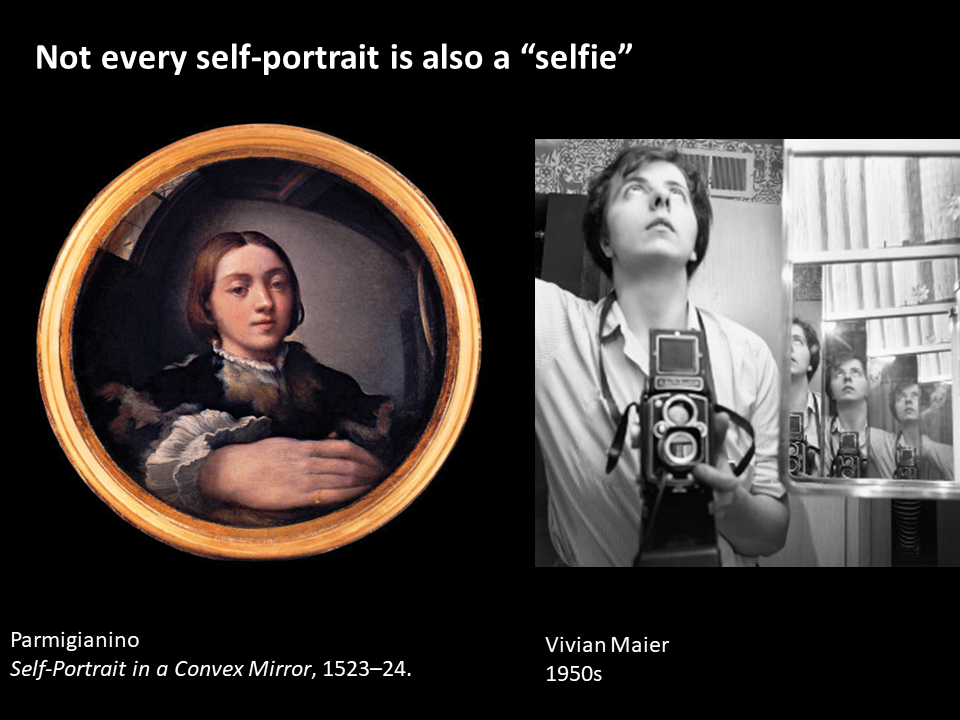

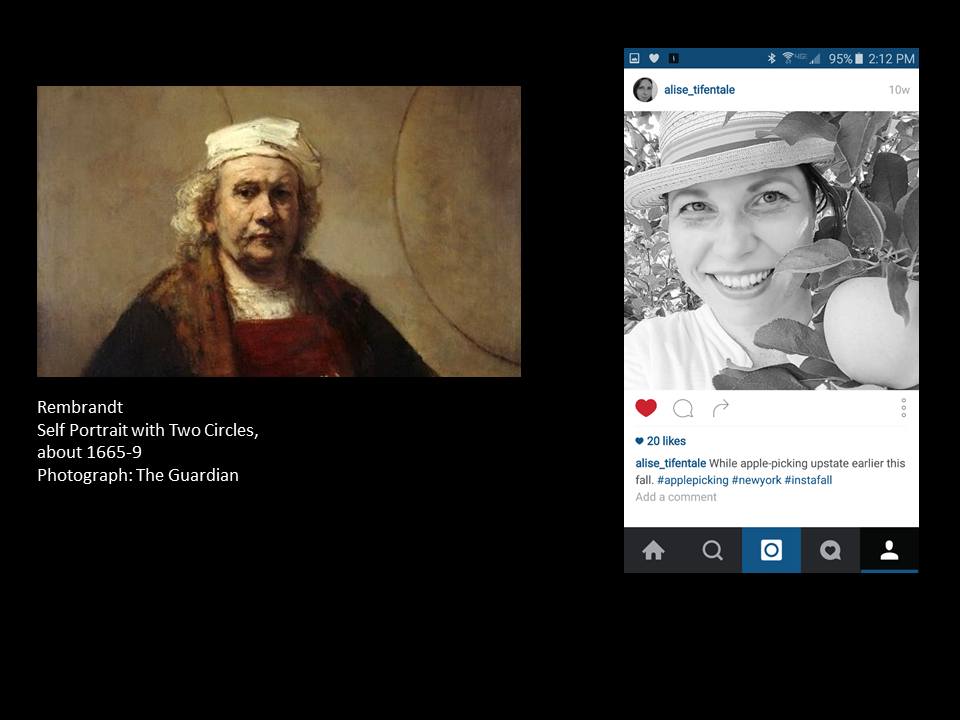

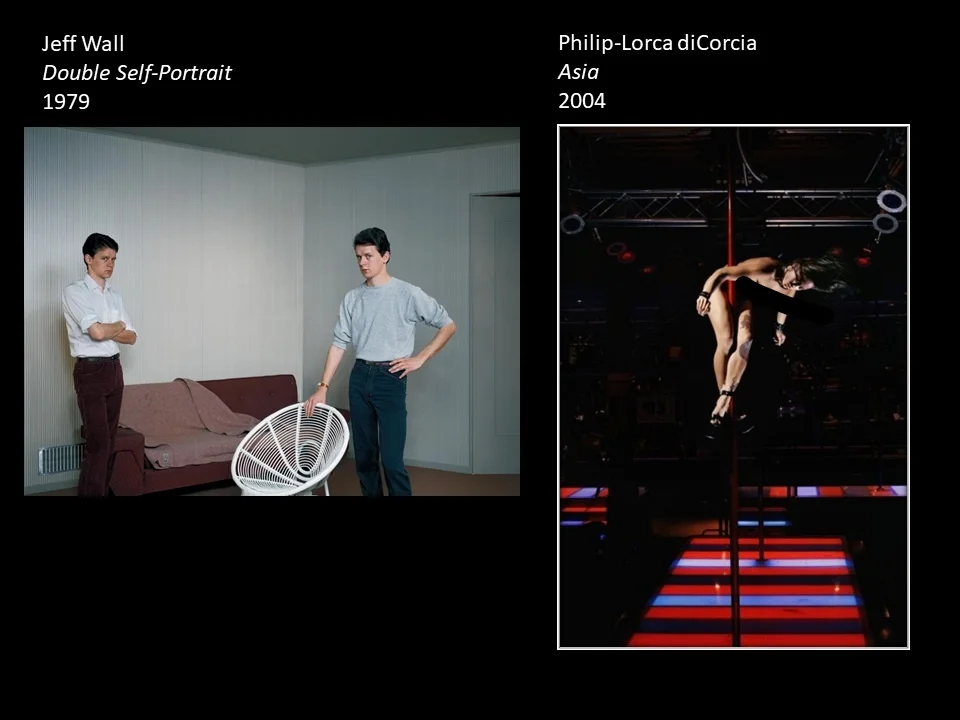

One thing that we can do, however, is to study a selected group of photographs. For example, I’d like to mention the notorious subgenre of popular photography, the selfie. We have studied it extensively at the Cultural Analytics Lab, since the launch of the project called Selfiecity. Since its emergence in 2013, however, the selfie has become one of the most attacked and misunderstood image types produced by the networked camera. Selfies on Instagram have been criticized, among else, as miserably failing successors to the painted self-portraits of the Renaissance and Baroque artists. Such comparisons, however, ignore the historical and cultural specificity of each case.

The approach to study a selected group of photographs such as selfies can be productive, but it is also dangerous because it deliberately extracts some photographs from their natural environment—it isolates these images from the networked camera, from this hybrid device of their making, editing, sharing, and viewing. And that can be misleading. Instagram photographs are not floating in some kind of vague space. They are not directly comparable to paintings, or even photographic prints. They have their own, very specific materiality because they are inseparable from the networked camera.

Individuals are using the platform of Instagram to create their galleries, and they are conveying all kinds of messages in the language of photography. One might ask—but are these messages important? The universe of Instagram photography equally embraces professional and amateur photographers, it is equally open to famous artists as it is to self-taught activists, it hosts sophisticated and highly designed galleries as well as collections of family snapshots, it is used by reality TV stars as well as small grassroots communities. This universe unites multiple aesthetic sensibilities and numerous social uses of photography. As such, Instagram offers a perfect sample of contemporary photography-based, global visual culture.

But it is not easy to define. It is not an exhibition, it is not an archive, it is not a group of like-minded avant-garde artists, it is not a photographers’ agency or a magazine. Instagram photography seems to be quite different from all that art and photography historians have been studying so far. One tool that can be extremely helpful is what Lev Manovich in his book Instagram and the Contemporary Image calls Instagramism—a term that describes the ways in which Instagram photographs “establish and perform cultural identities.” Manovich writes: