“Landscape as a Form of Escape: Apolitical Art and Politics in the Soviet Union between c. 1945 and 1991” is a talk I delivered at the mM Art Center in Pyeongtaek, South Korea, on January 28, 2023.

Download the summary of the talk as a pdf document here - it is a working version for the translators into Korean. The mM Art Center kindly provided the audience with a live simultaneous translation of my talk as well as with a printed booklet with the summary of my talk in both Korean and English.

Scroll down to browse selected slides from my talk.

I was invited to give this talk on the occasion of an exhibition based on the mM Art Center’s unique collection of apolitical art from the Soviet Union. Learn more about the mM Art Center: http://www.mmartcenter.com/

Our collaboration began already in 2021 when I was invited to contribute a brief essay about art in the Soviet Union, titled “The Lesser Known Romantic Side of Soviet Art,” for a catalogue of the collection, Good Morning USSR. Read more about it here: https://www.alisetifentale.net/article-archive/goodmorningussr

Abstract:

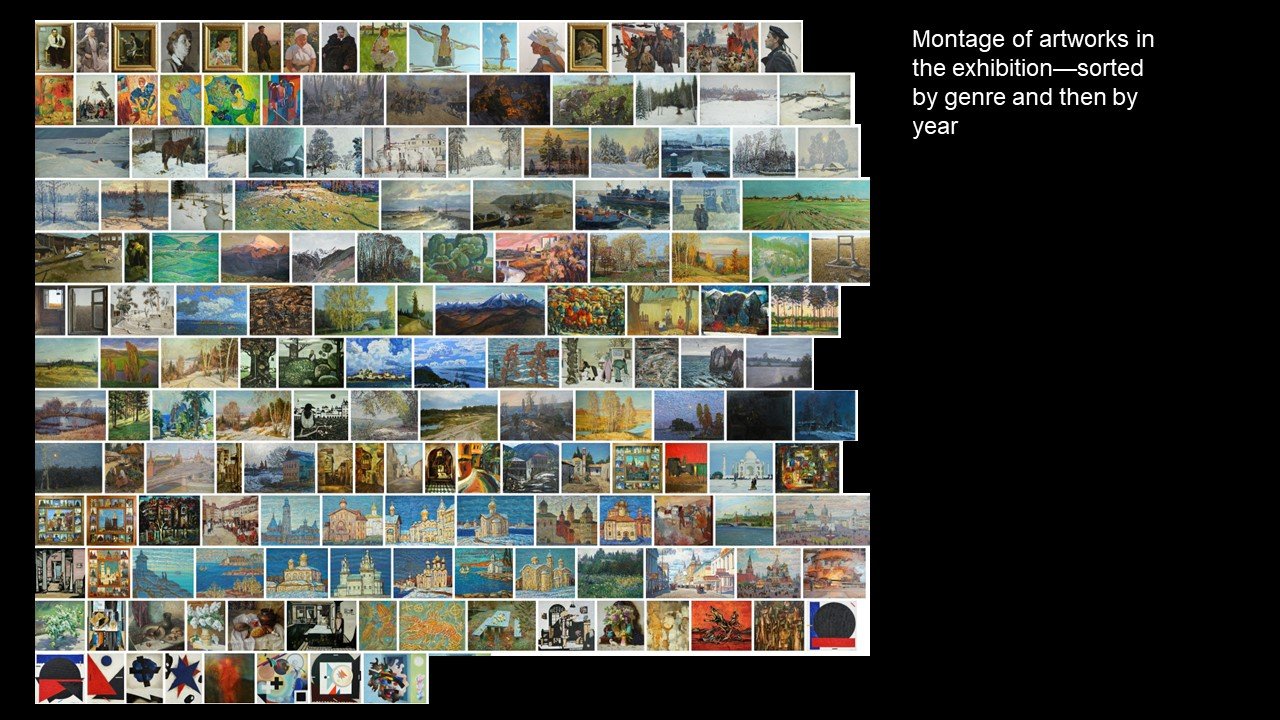

Within the highly politicized social and cultural environment of the Soviet Union, the more intimate genres of painting such as landscape offered a quiet route of escape from the requirements of public art to serve the government and the communist party. Most paintings in the mM Artcenter’s collection depict seemingly timeless views of nature, devoid of any obvious signs of modernity. However, the artists’ choice to focus on apolitical subjects was itself a political choice.

Although most of the paintings in the mM Artcenter’s collection show us beauty, serenity, and harmony, we should be careful not to romanticize life under an oppressive regime. Russian imperialism and colonialism have shaped much of the Soviet history. Now, these trends have resurfaced with the war in Ukraine. This talk examines the tradition of landscape painting on the background of broader cultural and political developments in the Soviet Union.

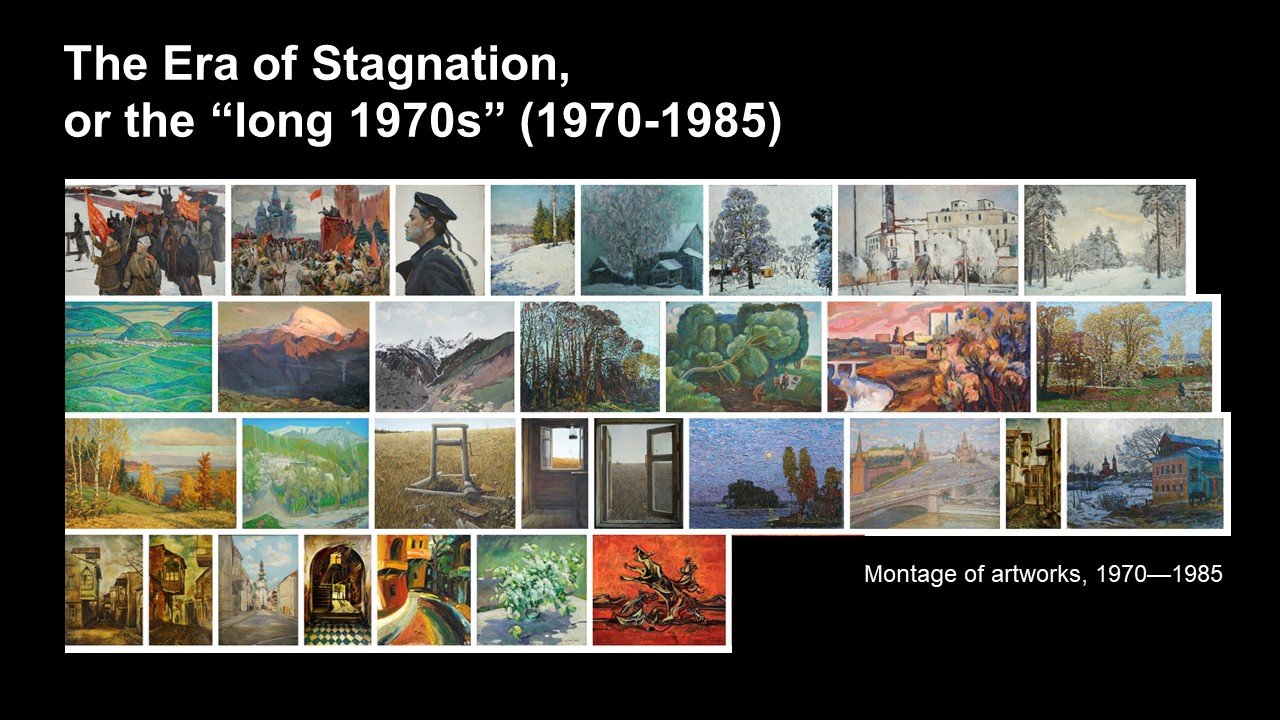

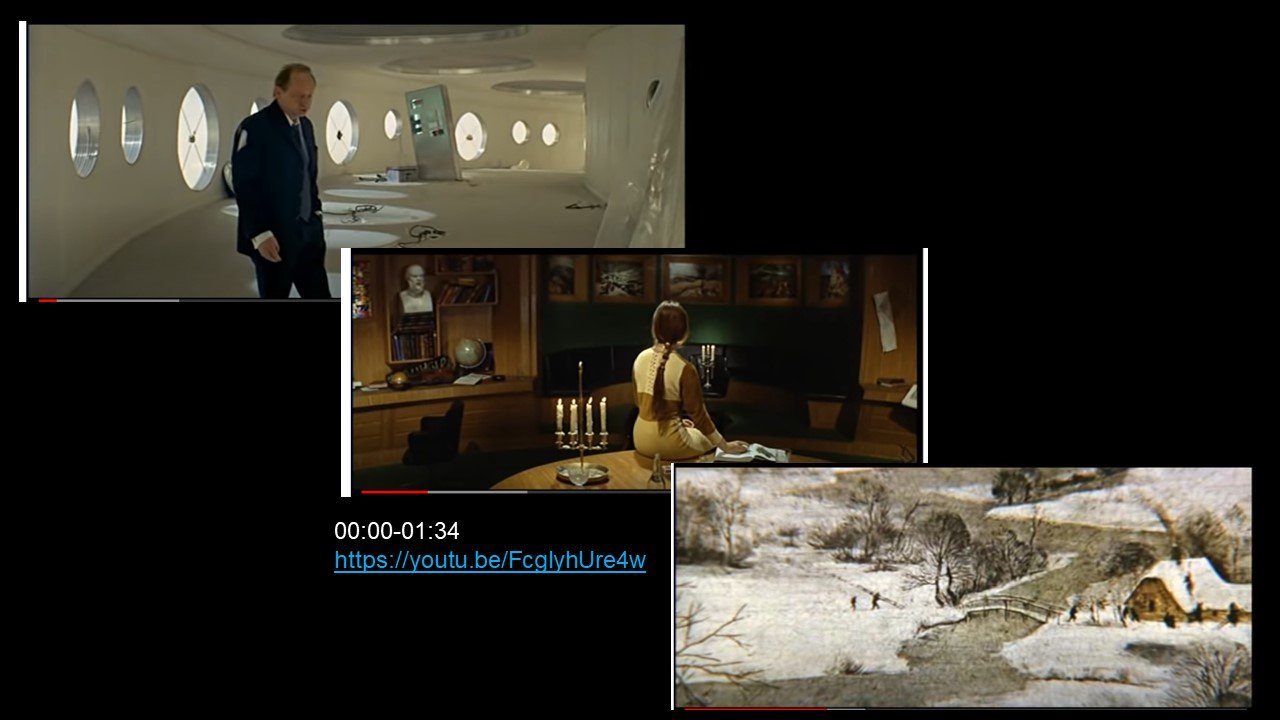

Departing from the late Russian Empire and the establishment of landscape painting tradition by the Peredvizhniki (the Wanderers) movement, the talk traces the history of apolitical art in the USSR. The dominance of realism was only briefly interrupted by the arrival of Russian and early Soviet avantgarde art in the 1910s and early 1920s. During Stalin’s regime in the 1930s, the concept of Socialist Realism was defined as the mandatory method of creative production for all Soviet artists, writers, photographers, filmmakers, and other creative professionals. Debates about Socialist Realism characterized the official public discourse on the arts until the 1990s. However, Socialist Realism was not a consistent and unified style, but rather a broad range of permissible styles and types of subject matter which, moreover, underwent numerous distinct stages over time. For example, the Thaw in the 1960s brought partial relaxation of the government control and opened the borders to international art, cinema, and literature. The following Era of Stagnation or the “long 1970s” with the “Bulldozer exhibition” reinforced limitations to freedom of expression, causing a proliferation of nonconformist and underground art events. Beginning in the second half of the 1980s, the Perestroika (reform) and Glasnost (openness) era was permeated by the anticipation of the Soviet Union’s imminent collapse whose spirit materialized in the extremely depressive and violent chernukha (dark) cinema and rock music openly calling for liberation.

While almost each decade in Soviet history developed its own visual culture, fashion, popular music, and trends in film and literature, landscape painting tradition apparently rejected most of these changes. By doing so, this tradition reflected the ubiquitous tension between the public and private worlds. Moreover, despite the pressure of russification, paintings in this collection also reveal some of the ethnic and cultural diversity of the fifteen republics that made up the Soviet Union after the Second World War.

Browse selected slides from my talk below.

I have the full set of all 68 slides with captions in English as well as Korean—if you’re interested in seeing the full set in any of these languages, feel free to email me and I’ll share the file with you.

Email me at [atifentale at gradcenter dot cuny dot edu] with your request or any other questions.