Albert Renger-Patzsch (1897-1966) was a German photographer, one of the most visible practitioners of the type of photography often called New Objectivity. The concept of such photography was a product of the culture of the Weimar Germany. After the World War II, Renger-Patzsch continued to teach and champion the New Objectivity photography. We can trace a genealogy of related approaches leading from Renger-Patzsch to Hilla and Bernd Becher, and from them to their students, the so-called Düsseldorf school photographers such as Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Thomas Ruff, and others. In the context of art history, this kind of photography is unmistakably recognized as art.

View a collection of Albert Renger-Patzsch's works at the Getty Museum.

Yet, I think it is important to keep in mind that Renger-Patzsch was actually teaching that photography and art are meant to be separate worlds, while his perhaps lesser known contemporary, Otto Steinert (1915-1978), was the one who advocated an artistic photography or a photographic art. Steinert called it Subjective Photography. As the name suggests, this kind of photography was expected to express the photographer’s subjective worldview. Steinert was also one of the founders of the important postwar photography trade fair Photokina (established in Cologne in 1950). Steinert was the creative leader of FotoForm group that was significant for German photography in the early 1950s. He also was an important teacher and founder of the Folkwang museum.

View a collection of Otto Steinert's works at the Folkwang Museum.

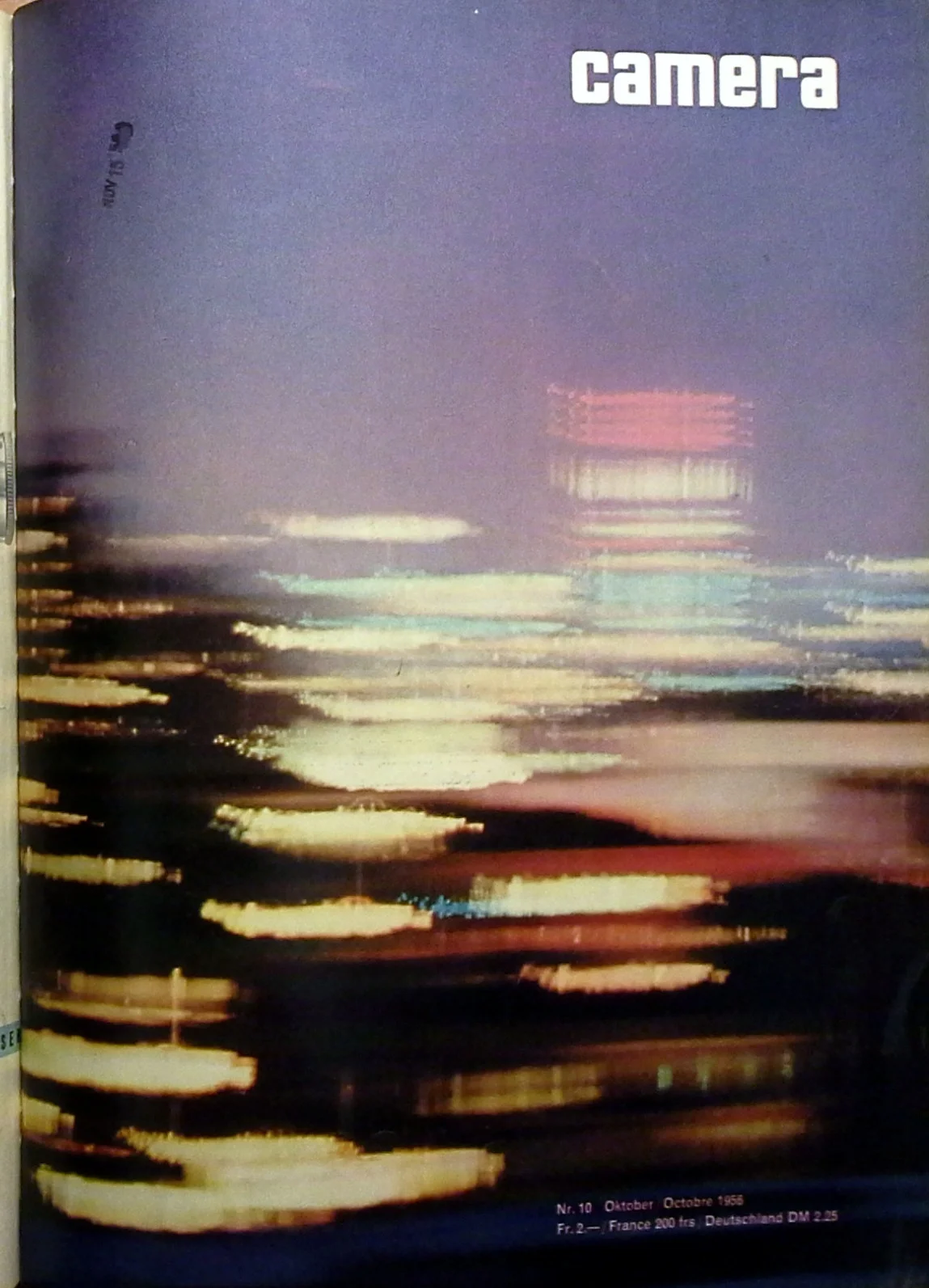

Example of photographic aesthetics that are reminiscent of the principles of Subjective Photography. Cover of Camera magazine, October 1956. Photo: “New York” by Suzanne Haussammann. Subjective Photography at its most typical, however, was black-and-white.

In an interesting historical turn, what was meant to be non-art, became the very epitome of art (as exemplified by Renger-Patzsch’s followers), whereas the most artistic photography of the 1950s (Steinert’s Subjective Photography) turned out to be a dead end, at least from the perspective of today's dominant art-historical narrative. But I’d like to emphasize that this was not yet so clear in the years following World War II. Well before the Bechers became world famous as artists, both the New Objectivity and the Subjective Photography were valid and much appreciated trends in contemporary photography.

Furthermore, it seems even likely that the 1950s was a time when Renger-Patzsch’s teachings sounded conservative and backwards for many, especially for those who thought that photography can be “artistic” and that photography is capable of expressing the individual experiences and emotions of an artist. These photographers and writers saw their desires answered in the Subjective Photography. The 1950s also was a time when many photographers and theoretical writers alike were fascinated with the idea of photography as a truly “universal” art—an art that can easily cross political and cultural borders, and help people communicate on peaceful terms (read more about this concept in one of the following blog posts).

In an article that summarizes his viewpoint, Renger-Patzsch lays out three basic ideas of his New Objectivity. First of all, he rejects pictorial photography because photography has its own aesthetic and does not have to borrow one from painting. It seems that he was using the concepts "pictorial" (or, rather, "painterly") and "art" interchangeably.

“This is, however, the legitimate task of photography: to recognize and to point out. When it seeks to interpret, photography largely oversteps its boundaries; interpretation should be left to art and, in certain cases, to science.”

Second, technical skills are essential for a photographer. Renger-Patzsch seems to have sincerely hated the automatic cameras that started to appear in the market during the 1950s.

Third, the main tasks of photography, according to Renger-Patzsch, are “exact reproduction of form,” “inventorization,” and “production of documents.” Basically that is exactly what the Bechers did and what their students continue to do. Not a single word about being artistic in that sense of the word that was implied by Steinert—nothing about capturing subjective or singular experiences, but quite the opposite.

“Photography is a graphic process of a special kind, neither art nor handicraft; its value results partly from an aesthetic and partly a technical judgement; because of its mechanical structure; it appears better suited to render justice to an object than to express artistic individuality.

(...)

The quality of a photograph is determined primarily by considerations which end with the release of the shutter. What is decisive thus takes place before the actual photographic activity: namely, the aesthetic judgement (the recognition of the object) and the technical judgement (the weighing of whether the recognized object can be translated into a valid photo.) The automatic camera, which relieves the user of all possibility of reflection, thereby destroys photography as an intellectual accomplishment.”

Interestingly enough, Renger-Patzsch saw the creative process of making a photograph only in the moment when a photograph is being conceived and taken. Of course, I am simplifying the issue, but from what Renger-Patzsch wrote we can infer that the two other equally important steps of making a photograph, namely the process of developing the negative and making the print, were completely irrelevant for him and were treated as transparent, automatized or neutral. Photographers who in the 1950s associated themselves more with the Subjective Photography, perhaps would argue that “conceiving” and “taking” the image is just one half of the process, after which you have to make it visible, and this other half of the photographic process also involves some important aesthetic as well as technical judgements.