Paper presented at the 27th Annual Interdisciplinary Conference in the Humanities, University of West Georgia, Carrollton, GA, November 1–3, 2012.

Photography in the Soviet Union and in the so-called Communist Bloc countries in Europe developed quite differently from the west after the World War II. In the Soviet Union, in the absence of free art market and in circumstances of severely limited freedom of expression and restricted human rights in general, all forms of art were integrated into the larger framework of Soviet communist ideology and politics. Art photography had a very marginal place in this framework.

In this paper, I am addressing the role of camera clubs that initially were established as places of control and indoctrination of workers, but that in some exceptional cases became platforms of relative freedom of style and communication for artists, partly protected by their hobbyist status and not belonging to the official arts establishment. The two decades following Stalin’s death in 1953 are discussed, starting with the so-called Khrushchev’s Thaw (the mid-1950s – early 1960s).

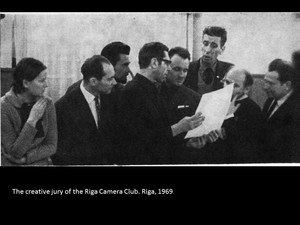

The paper focuses on a case study of Riga Camera Club, founded in 1962 in Riga, capital city of Latvia (then Soviet Socialist Republic of Latvia). This club is viewed as one of the leading entities raising discussions and public awareness on art photography in the Soviet Union. It can be argued that all three Baltic countries annexed to the Soviet Union after the war—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, despite being geographically small, had a significant influence upon arts and culture in general of the postwar Union. These countries had retained their distinct European cultural identities even under cultural policies and infrastructures imposed by the Soviet government. During the interwar years, they had enjoyed all freedoms and challenges of democratic nation-states, and their cultural milieus remained different from that of Russia and the rest of the USSR.