The Selfie: Making sense of the “Masturbation of Self-Image” and the “Virtual Mini-Me.” Selfiecity, 2014. This essay reviews some of the recent debates on the selfie (at the time of writing - late 2013 and early 2014) and places it into a broader context of photographic self-portraiture, investigating how the Instagrammed selfie differs from its precursors, as well as mapping out avenues for further research and interpretation of the results obtained in Selfiecity.

Read moreSão Paulo photographers in FIAP, 1950-1965

"São Paulo photographers in global context: Brazilian participation in the International Federation of Photographic Art, 1950–1965." Research paper presented at the conference In Black and White: Photography, Race, and the Modern Impulse in Brazil at Midcentury at The Graduate Center, City University of New York, May 3, 2017.

Read moreThe Misunderstood 'Universal Language' of Photography

"The Misunderstood 'Universal Language' of Photography: The Fourth FIAP Biennial, 1956." Paper presented at the conference Art, Institutions, and Internationalism: 1933–1966 in New York City, March 7, 2017.

Read moreThe 'Cosmopolitan Art': The FIAP Yearbooks of Photography, 1954–60

“The ‘Cosmopolitan Art:’ The FIAP Yearbooks of Photography, 1954–60.”

Paper presented at the 105th Annual CAA Conference, New York City, February 17, 2017.

Photo: Elizabeth Cronin.

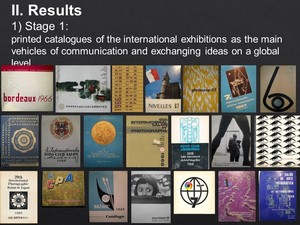

“It is a diversified, yet tempered picture book containing surprises on every page, a mirror to pulsating life, a rich fragment of cosmopolitan art, a pleasure ground of phantasy”—this is how, in March 1956, the editorial board of Camera magazine introduced the latest photography yearbook by the International Federation of Photographic Art (Fédération internationale de l'art photographique, FIAP). This paper will analyze this “cosmopolitan art” of photography in the first four FIAP yearbooks, published between 1954 and 1960 on a biennial basis.

FIAP, a nongovernmental transnational organization, was founded in Switzerland in 1950 and aimed at uniting the world’s photographers. Its members were national associations of photographers, representing 55 countries: seventeen in Western Europe, thirteen in Asia, ten in Latin America, six in Eastern Europe, four in Middle East, three in Africa, one in North America, and Australia. Photographs for FIAP yearbooks were selected from works submitted by all member associations.

The resulting large format hardcover photo-books consisted of average 120 full-page photogravure reproductions, grouped by country. These yearbooks, I argue, complicated and politicized the understanding of photographic art in the 1950s. On one side, the yearbooks presented a groundbreaking attempt to reject Western Europe as the only center of creativity in favor of a model of global participation. On the other, the organization’s ambition to survey the cultural diversity of the world at times was limited by ethnographic stereotyping (e.g., recurring depictions of Catholic priests or nuns in the Spanish section or portraits of geishas from Japan).

This paper was part of the panel "Photography in Print," moderated by Andrés Mario Zervigón, Rutgers University. The two other presenters in our panel were C.C. Marsh, The University of Texas at Austin, who presented Between Art and Propaganda: Photo-Monde in the Service of the UN, and Meredith TeGrotenhuis Shimizu, Whitworth University, who presented The Spectacularization of Disaster: Photographs of Destruction in Commemorative Coffee Table Books.

Thank you to all who came to our panel. It was a great honor to present my research and discuss it with the two other scholars in our panel.

The panel "Photography in Print" at the CAA 2017. From the left: Meredith TeGrotenhuis Shimizu, C.C. Marsh, and Alise Tifentale.

The Exceptional and the Everyday: 144 Hours in Kyiv

“The Exceptional and the Everyday: 144 Hours in Kyiv,” co-authors: Jay Chow, Lev Manovich, and Mehrdad Yazdani.

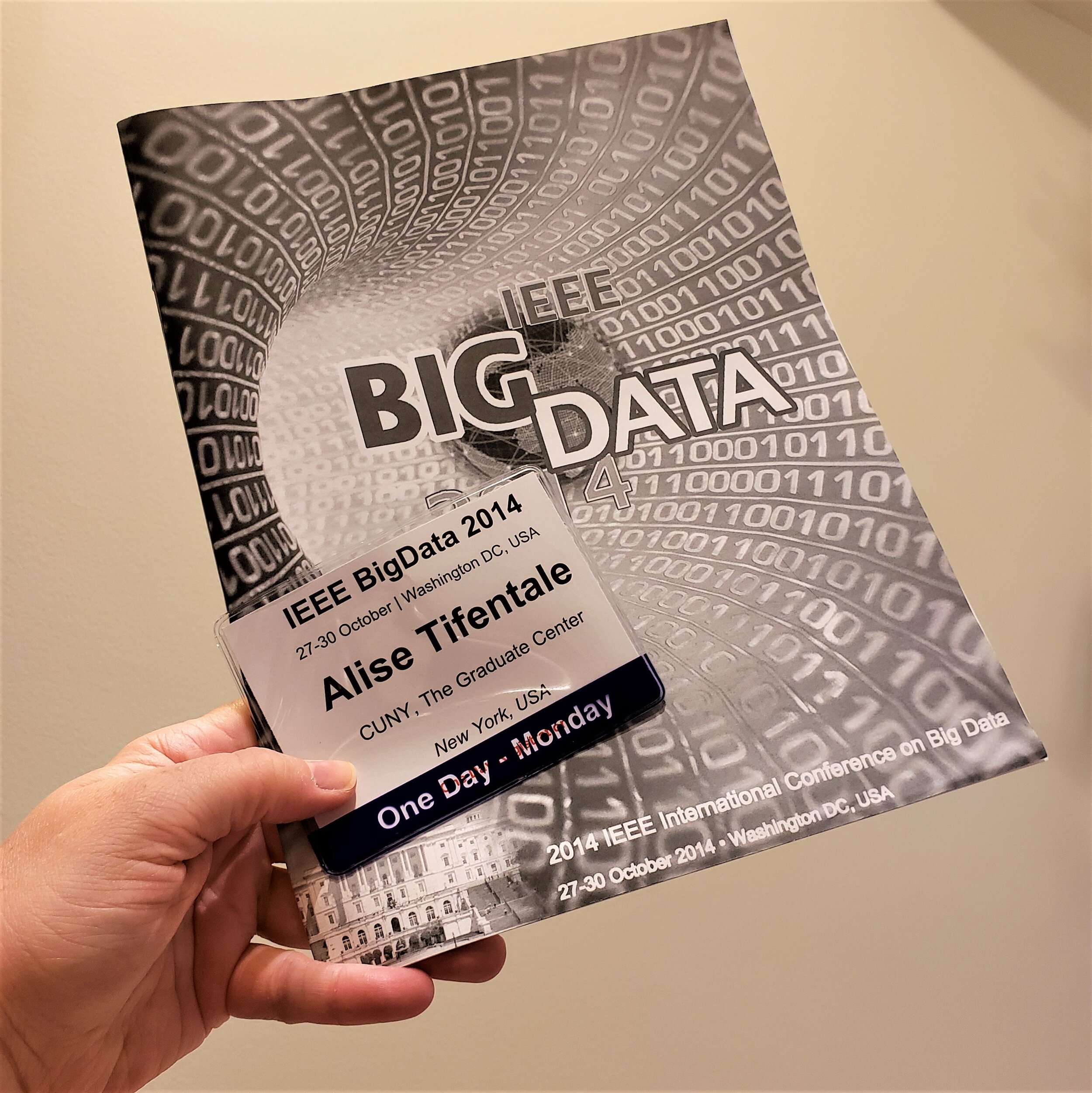

Paper presented at the Big Humanities Data Workshop, The Second IEEE Big Data 2014 Conference, Washington, DC, October 27, 2014. This version of the paper is published in IEEE Big Data 2014 Conference Proceedings (2014), 77-84.

This paper presents and discusses some the findings of the research project The Exceptional and the Everyday: 144 Hours in Kyiv (2014) which I co-authored with Lev Manovich, Mehrdad Yazdani, and Jay Chow.

Abstract:

How can we use computational analysis and visualization of content and interactions on social media network to write histories? Traditionally, historical timelines of social and political upheavals give us only distant views of the events, and singular interpretation of a person constructing the timeline. However, using social media as our source, we can potentially present many thousands of individual views of the events. We can also include representation of the everyday life next to the accounts of the exceptional events. This paper explores these ideas using a particular case study – images shared by people in Kyiv on Instagram during 2014 Ukrainian Revolution. Using Instagram public API we collected 13208 geo-coded images shared by 6165 Instagram users in the central part of Kyiv during February 17-22, 2014. We used open source and our own custom software tools to analyze the images along with upload dates and times, geo locations, and tags, and visualize them in different ways.

See also my essay "Iconography of the Revolution" on the website of the project. In this essay, my research question is: What is the visual grammar of a revolution? In order to grasp the characteristics of the images related to the 2014 Ukrainian Revolution on social media, I suggest we look back at some of the most iconic depictions of similar events such as the social upheavals in the streets of Paris in 1848, 1871, and 1968.

Thibault. Barricades on Rue Saint-Maur, June 25, 1848. Paris, 1848.

Pierre-Ambroise Richebourg. Barricades of the Paris Commune Near Hôtel de Ville and the Rue de Rivoli. April 1871, Paris

Gilles Caron. Protest in Rue Saint-Jacques. Paris, May 6, 1968.

Montage of Instagram images depicting the barricades in Kyiv, 2014. See more images and analysis on the project website.

Our Muddy Boots on Their Marble Floor: Identity and Self-Fashioning in Latvian Contemporary Art

“Our Muddy Boots on Their Marble Floor: Identity and Self-Fashioning in Latvian Contemporary Art.”

Paper presented at The Yale Conference on Baltic and Scandinavian Studies organized by the Association for the Advancement of Baltic Studies (AABS), the Society for the Advancement of Scandinavian Study (SASS), and the European Studies Council at Yale University. New Haven, CT, Yale University, March 13–15 , 2014.

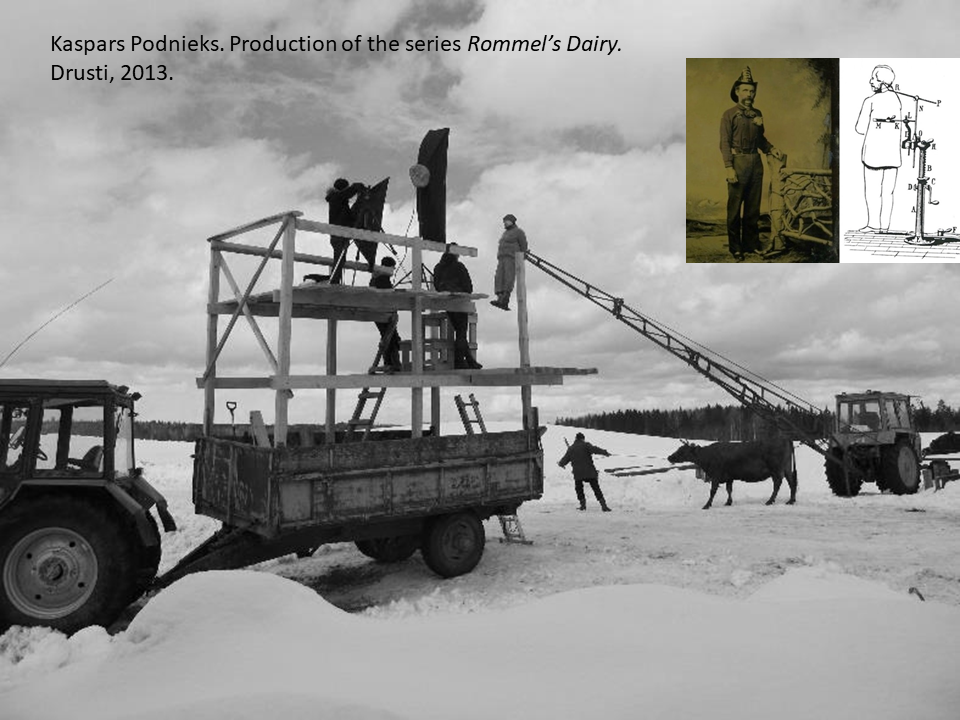

In this paper I address some of the challenges that contemporary art and artists from Latvia encounter in the globalized art world. The paper is based on my experience as a co-curator of North by Northeast, the Latvian national participation in the 55th International Art Exhibition of Venice Biennale, which was open to the public from June to November, 2013, in Venice, Italy. The pavilion of Latvia showcased newly commissioned works by two Latvian artists: Krišs Salmanis (b. 1977) and Kaspars Podnieks (b. 1980).

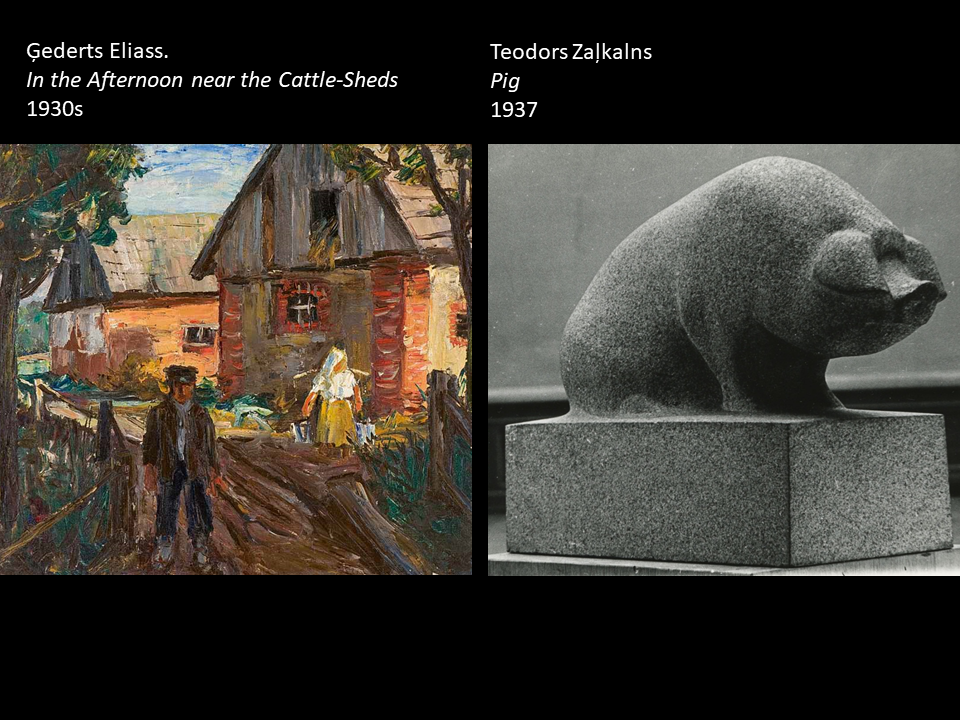

Both artists in their work engage in a dialogue with the past by evoking and also subverting concepts that have been essential for Latvian art from its beginnings in the 19th century through the interwar years as well as during the Soviet period. This dialogue questions national identity of a country whose status has been shifting, unstable, and always marginalized. Both artists Podnieks and Salmanis in their new work talk about location and dislocation, about instability, about being uprooted and removed from one’s native land, about the uncertain identity of an individual or even the whole nation.

Photographers’ Escape Route: Camera Club as a Place of Control and a Platform of Resistance in the Postwar Soviet Union

Paper presented at the 27th Annual Interdisciplinary Conference in the Humanities, University of West Georgia, Carrollton, GA, November 1–3, 2012.

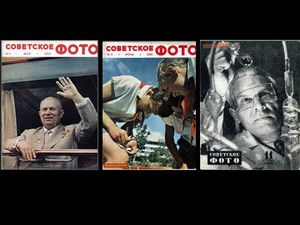

Photography in the Soviet Union and in the so-called Communist Bloc countries in Europe developed quite differently from the west after the World War II. In the Soviet Union, in the absence of free art market and in circumstances of severely limited freedom of expression and restricted human rights in general, all forms of art were integrated into the larger framework of Soviet communist ideology and politics. Art photography had a very marginal place in this framework.

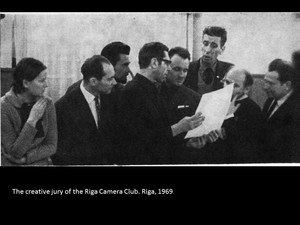

In this paper, I am addressing the role of camera clubs that initially were established as places of control and indoctrination of workers, but that in some exceptional cases became platforms of relative freedom of style and communication for artists, partly protected by their hobbyist status and not belonging to the official arts establishment. The two decades following Stalin’s death in 1953 are discussed, starting with the so-called Khrushchev’s Thaw (the mid-1950s – early 1960s).

The paper focuses on a case study of Riga Camera Club, founded in 1962 in Riga, capital city of Latvia (then Soviet Socialist Republic of Latvia). This club is viewed as one of the leading entities raising discussions and public awareness on art photography in the Soviet Union. It can be argued that all three Baltic countries annexed to the Soviet Union after the war—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, despite being geographically small, had a significant influence upon arts and culture in general of the postwar Union. These countries had retained their distinct European cultural identities even under cultural policies and infrastructures imposed by the Soviet government. During the interwar years, they had enjoyed all freedoms and challenges of democratic nation-states, and their cultural milieus remained different from that of Russia and the rest of the USSR.

Unconventional Art: The Emergence of New Photographic art in the Post-Stalin Soviet Union

“Unconventional Art: The Emergence of New Photographic art in the Post-Stalin Soviet Union.” Paper presented at the SECAC (South Eastern College Art) annual conference Collisions: Where Past Meets Present, Meredith College, Durham, NC, October 17–20, 2012.

In this paper I explore photography as a new and unconventional art emerging in the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death in 1953, during the period often called the Khrushchev’s Thaw. I discuss the paradox that this art appears surprisingly apolitical, seemingly socially passive, and escapist, but at the same time this passivity in some cases functioned as an active political position, or at least as a statement of a certain level of artistic freedom in the given political circumstances.

I also introduce some major difficulties of analysis and interpretation of this art from the perspective of western canon of art history and photography, which can easily accommodate the Soviet avant-garde photography of the 1920s and early 1930s, but which has no place for later, postwar developments that do not follow the historical narrative of advanced practice of photography in the western culture.

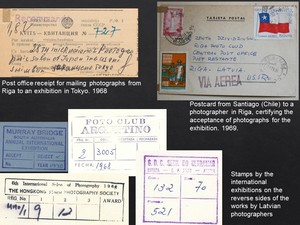

Photographers Breaking the Iron Curtain: The Role of Informal International Communication Networks in Soviet Photography

“Photographers Breaking the Iron Curtain: The Role of Informal International Communication Networks in Soviet Photography.” Paper presented at the IAMCR (International Association for Media and Communication Research) annual conference Cities, Creativity, Connectivity, Kadir Has University, Istanbul, Turkey, July 13–17, 2011.

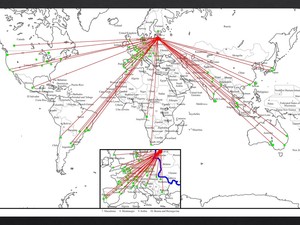

The paper discusses the role of the information exchange networks in the development of photography in the Soviet Union in the 1960s and 1970s, and presents a study on photographers from the Camera Club of Riga (Latvia) who managed metaphorically to break through the Iron Curtain and participated in photography exhibitions worldwide.

Although photography from the Soviet Union in general has been analyzed in different contexts both in post-Soviet countries and in the West, the specific fields of amateur photography and art photography in the 1960s and 1970s still have not been covered completely. Besides, history of photography in the Soviet Union often has been identified with history of Russian photography, only occasionally mentioning national schools of other Soviet republics with different cultural and social circumstances.

This paper outlines some of the complex issues related to the understanding of institutional framework of amateur and art photography in the Soviet Union in the 1960s and 1970s, and focuses in particular on Riga Camera Club (Latvia), an amateur organization that became one of the most visible hubs of creative photography in the Soviet Union in the 1960s, and whose members succeeded in participating in numerous international photography exhibitions outside the USSR.

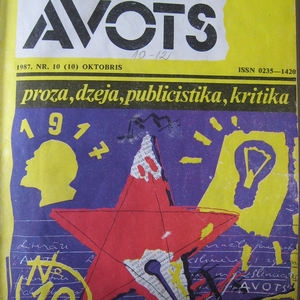

The New Wave of Photography: The Role of Documentary Photography in Latvian Art Scene During the Glasnost Era

“The New Wave of Photography: The Role of Documentary Photography in Latvian Art Scene During the Glasnost Era” in Stephen Andrew Arbury and Aikaterini Georgoulia, eds., Visual and Performing Arts (Athens: Athens Institute for Education and Research, 2011), 121-128. Proceedings of the 2nd Annual International Conference on Visual and Performance Arts at the Athens Institute for Education and Research, Athens, Greece (6–9 June, 2011). ISBN 978960954965.

A major shift in the role and perception of photography as a medium of the visual arts in Latvia took place on the background of the political events in the mid-1980s that ultimately led to the collapse of Soviet Union and the Communist bloc. In Latvia, then one of the Soviet Republics, the idea of restoring the country’s independence dominated the public debates. Also the visual arts often were discussed in terms of the current political and social changes. Following the pattern of neglecting the past, in the mid-1980s a ‘new wave of photography’(Demakova, 1999) was rising in Latvia. The proposed paper describes the social and aesthetic context of the ‘new wave’ of Latvian photography, and discusses the role of the documentary imagery in the visual arts. Although Latvian photographers were ‘freed to picture even the ugliest truths’ (Svede 2004), the new documentary imagery was not confused with photojournalism with its more direct and sometimes aggressive stances and rarely it represented any ‘shock-pleasure’ (Welchman, 1994)value associated in the West with photography from the Soviet Union.

The paper analyses the photographs that ‘shifted into the dominant “fine art” context’ within the specific Soviet and early post-Soviet visual culture in Latvia. Several Latvian photographers earned recognition during the late 1980s after their participation in exhibitions outside the Soviet Union. These photographers shaped and defined photography as one of the ‘new media’ (Demakova, 2000) in Latvian contemporary art of the early 1990s.The paper adds an insight into the changing attitudes towards documentary photography in Latvia during the glasnost era.

Socialist Realism, Capitalist Realism, and Documentary Photography

"Socialist Realism, Capitalist Realism, and Documentary Photography: A Comparison of Illustrations from a Soviet Newspaper (1977) and a Global Lifestyle Magazine (2007)," in Mythology of the Soviet Land (Riga: Latvian National Museum of Art, 2009), 268-290. ISBN 9789984807225. Proceedings of the international academic conference Problems of Interpretation of the Art of Socialist Realism, Riga, Latvia, May 19-20, 2008.

Although the term “Socialist Realism” is mostly used to refer to painting, sculpture, literature, and film, the principles of the Soviet ideology and Socialist Realism are also reflected in the photography of the Soviet period. This can be seen both in press photography and in representative photography that made up the majority of photographic materials that were seen in the Soviet public spaces.

This paper focuses on press photographs that were published in Soviet Latvia between the late 1950s and late 1970s. I trace the application of some of the principles of Soviet Socialist Realism and offer a few parallels and comparisons between Soviet-era press photographs and the flourishing genre of the capitalist world, advertising photography. The paper is based on visual materials such as illustrated books about economy of Soviet Latvia, press photographs, and the photo chronicle that was delivered to newspapers in Soviet Latvia by the LATINFORM news agency on a regular basis under the title “Our Republic in Photographic Images.”

My comparison of Soviet-era press photos to advertising photographs from the capitalist world is based on the similar functions assigned to these images. The task of the Soviet press photograph was to create and uphold the impression the Soviet Union’s victorious progress. They served as an endless “advertising” of the Soviet state’s ideals—collectivism, superiority and achievements of the proletariat. In capitalist economy, commercial advertising photography serves similar goals: to create and uphold the impression of the “goodness” of capitalist economy. This comparison suggests that the media under any kind of state system or economy publish ideologically charged photographs, very often pretending that the images are actually something else, that they represent “truthful” and therefore highly believable evidence that has been photographed, i.e. collected by mechanical—objective—means.”