“To Put Things into Order.” Review of exhibition This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, February 11 - June 3, 2012. Published in Studija 84, no. 3 (2012).

Read moreExhibition review: Tom Sachs, "Space Program: Mars" at the Park Avenue Armory, New York

“Admirable Human Error, or What Drinking and Welding can Lead to.” Review of Tom Sachs solo exhibition Space Program: Mars at the Park Avenue Armory, New York, May 16 — June 17, 2012. Published in Studija 85, no. 4 (2012).

Read moreExhibition review: dOCUMENTA (13)

“How to Rectify All Mistakes at Once” Review of dOCUMENTA 13 in Kassel, Germany, from June 9 to September 19, 2012. Published in Studija 86, no. 6 (2012): 14 - 23.

Read moreExhibition review: Art of Another Kind at the Guggenheim, New York

“How Quickly Does Avant-garde Age?” Review of exhibition Art of Another Kind: International Abstraction and the Guggenheim, 1949–1960 on view at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, June 8 - September 12, 2012. Published in Studija 87, no. 6 (2012): 8-17.

Read moreWestern Rock Videos of the 1980s and 1990s in the Soviet Union

“'The Place I Wanted to Live In’: Western Rock Videos of the 1980s and 1990s in the Soviet Union,” in Maija Rudovska, ed., Inside and Out (Riga: kim? Contemporary Art Center, 2012), 2-9. ISBN 9789934820069.

Rock music is only possible when you are young. Rock stars on stage would jump and sweat through some kind of Dyonisian rituals, accompanied by the energetic, emotionally uplifting sound of their music. Live concert recordings made up a large part of the 1980s music videos, and the ecstatic atmosphere in these videos was often underlined by shots of excited fan crowds. For example, such videos as “You Give Love a Bad Name” (1986) by Bon Jovi, “Final Countdown” (1986) by Europe, “Love Removal Machine”, “Lil’Devil” (1987) and “Wild Hearted Son” (1991) by The Cult, “Everybody Loves Eileen” and “I’ll Never Let You Go” (1990) by Steelheart, and “Monkey Business” (1991) by Skid Row manifest this tendency.

The fact that these rock stars – men - are using make-up and have long, “feminine” hairdos, can suggest a certain sexual ambiguity or at least uncertainty. Or perhaps the tights, eyeliners, and perm rather functioned as attributes of emphasized masculinity? Manifestations of androgyny or uncertain gender identity in the "cock rock" world can be interpreted as a proletarian offspring of the aristocratic dandyism of the 18th and 19th centuries. For example, notice how the aesthetic refinement of George Byron, Oscar Wilde, and Aubrey Beardsley was recaptured by David Bowie in the 1970s. In the 1980s this sexual undecidability was reduced to the standard combo of long hair and skinny leather pants. If rock music of this era had any true macho hero at all, it could only have been the demonic Glenn Danzig, who at the time had the most athletic torso, the most menacing look, and who could easily tame an alligator with his bare hands (see the video for “I’m the One,” 1990).

The Peasant Woman Leads the Dance: Some Ambiguities Presented by Vera Mukhina’s Sculpture

“The Peasant Woman Leads the Dance: Some Ambiguities Presented by Vera Mukhina’s Sculpture,” Russian Art & Culture 1 , no. 1 (2012): 7-15. Winner of the First Prize in Russian Art & Culture Postgraduate Writing Competition 2012. View the full issue of the journal for free here on Issu.

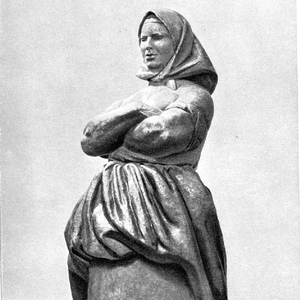

Russian sculptor Vera Mukhina (1889-1953) is most widely known as the artist of the grandiose stainless-steel sculpture Worker and Collective Farm Woman (1937), which crowned the Soviet pavilion in the Paris International Exposition of 1937, strategically located opposite the German pavilion.

However, this sculpture does not exhaust Mukhina’s oeuvre. Another challenging topic for an art historian is her Peasant Woman (1927), recently discussed at length by Bettina Jungen (“Vera Mukhina: Art between Modernism and Socialist Realism,” Third Text 23, no. 1 (2009): 35-43).

In this article, I am addressing some of the issues raised by Jungen, especially the opposition between the formalistic and politicized readings of the Peasant Woman. In addition, this article views Mukhina’s sculpture in terms of gender and class notions of the ideological background from which it emerged. Finally, I also discuss the artist’s relationship with the official art establishment in these terms as well, considering Mukhina’s upbringing in a pre-Revolution bourgeois family and her career as one of few female artists in the theoretically emancipated but in reality largely patriarchal Soviet official art institutions. By identifying some ambiguities in the current criticism and interpretations of Soviet official art, I hope to propose some perspectives for further inquiry that would lead to a thorough understanding of the contradictory and multilayered history of the official art in the Soviet Union.

The First Exhibition of Fine Art Photography in Latvia after World War II. 1957-1958

“The First Exhibition of Fine Art Photography in Latvia after World War II. 1957–1958,” Art History & Theory 15 (2012): 26-33. Article in Latvian with a summary in English.

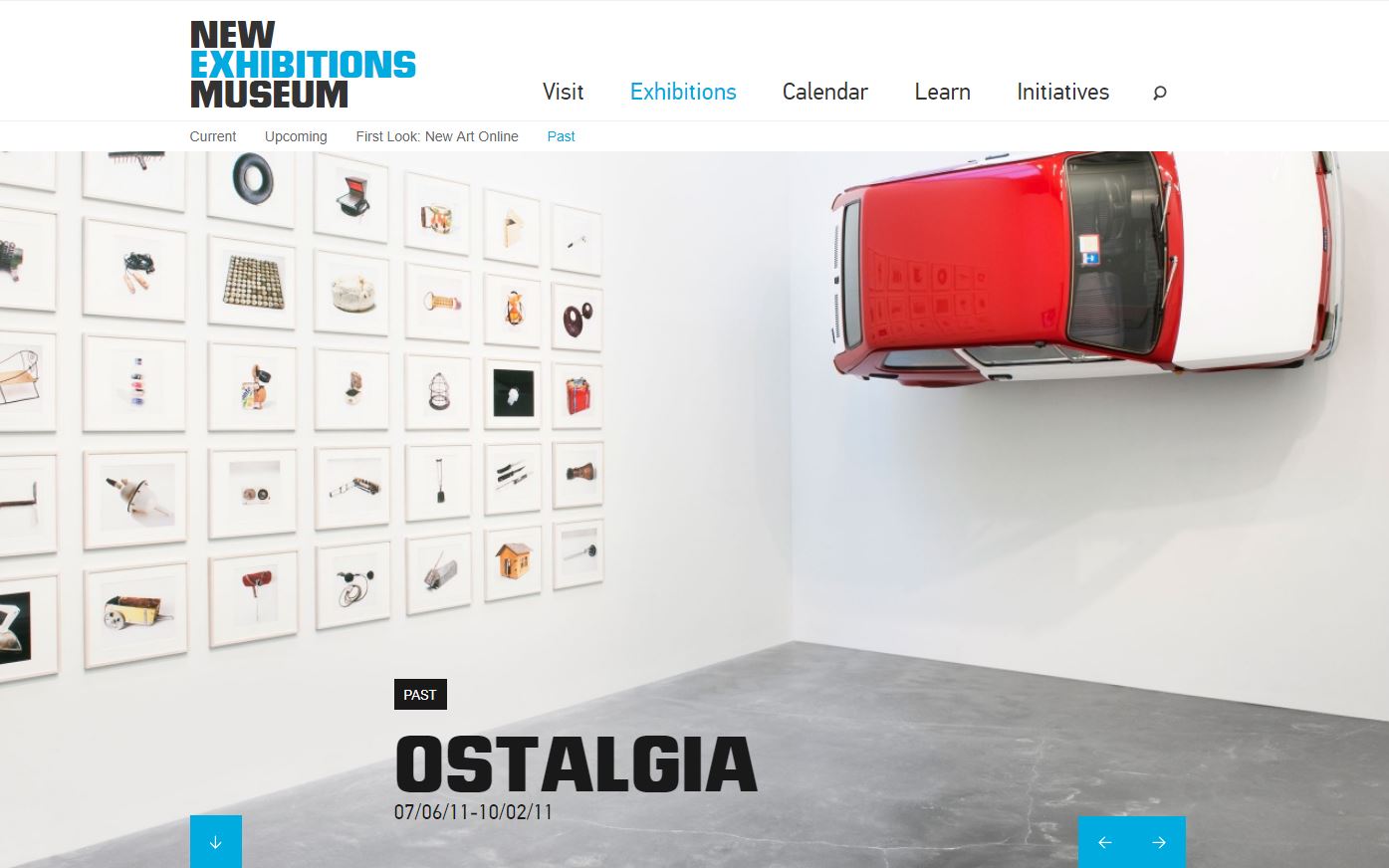

Read moreExhibition review: Ostalgia at the New Museum, New York (ARTMargins)

“Ostalgia at the New Museum (Review Article),” ARTMargins, March 5, 2012.

Read the article on ARTMargins website for free: https://artmargins.com/ostalgia-the-new-museum/

Check out also my other review of Ostalgia, published in Studija 81, no. 6 (2011) — pdf available here!

Excerpt from the review:

Conceived as “a survey devoted to Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Republics,” this exhibition represents a politicized, exoticized, and marginalized view of art from the former Soviet empire, making the Communist past, or, more precisely, the Western notion of it, the central axis of the show.

Deliberately blurred notions of geography and chronology complicate the rational coherence of the show, suggesting that diverse individual artistic practices and cultural backgrounds (from Central, Eastern, Southern, Northern European and Asian countries) belong to the same cultural milieu. Arguably the dialogue of art with a totalitarian regime creates the otherness that the Western audiences most often expect from the art of the former Communist bloc. Emphasizing this dialogue conveys the same simplified identity of the Other that has been continuously constructed in the West since the late 1960s by such seemingly contradictory players as leftist intellectuals and the capitalist art market, according to Éva Forgács.

Ostalgia encourages the canonization of works that reflect the tastes and formal preferences of a narrow circle of mainly Western collectors, and narratives by mainly Russian critics and theoreticians. Art from a large part of Europe therefore seems doomed to be viewed only as a heroic gesture of political resistance that can easily “fit into either the Western or the Russian narrative,” without individual artists, trends, or schools having a distinct, singular voice outside these two grand narratives.

View selected works from the exhibition on the New Museum's website.

Read full article for free on the ARTMargins website or download a pdf!

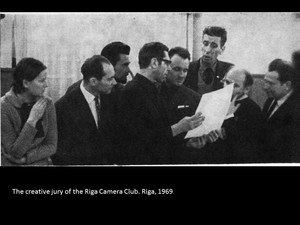

Photographers’ Escape Route: Camera Club as a Place of Control and a Platform of Resistance in the Postwar Soviet Union

Paper presented at the 27th Annual Interdisciplinary Conference in the Humanities, University of West Georgia, Carrollton, GA, November 1–3, 2012.

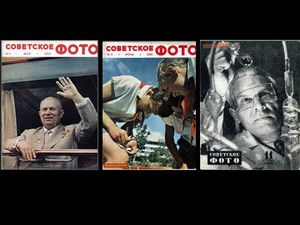

Photography in the Soviet Union and in the so-called Communist Bloc countries in Europe developed quite differently from the west after the World War II. In the Soviet Union, in the absence of free art market and in circumstances of severely limited freedom of expression and restricted human rights in general, all forms of art were integrated into the larger framework of Soviet communist ideology and politics. Art photography had a very marginal place in this framework.

In this paper, I am addressing the role of camera clubs that initially were established as places of control and indoctrination of workers, but that in some exceptional cases became platforms of relative freedom of style and communication for artists, partly protected by their hobbyist status and not belonging to the official arts establishment. The two decades following Stalin’s death in 1953 are discussed, starting with the so-called Khrushchev’s Thaw (the mid-1950s – early 1960s).

The paper focuses on a case study of Riga Camera Club, founded in 1962 in Riga, capital city of Latvia (then Soviet Socialist Republic of Latvia). This club is viewed as one of the leading entities raising discussions and public awareness on art photography in the Soviet Union. It can be argued that all three Baltic countries annexed to the Soviet Union after the war—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania, despite being geographically small, had a significant influence upon arts and culture in general of the postwar Union. These countries had retained their distinct European cultural identities even under cultural policies and infrastructures imposed by the Soviet government. During the interwar years, they had enjoyed all freedoms and challenges of democratic nation-states, and their cultural milieus remained different from that of Russia and the rest of the USSR.

Unconventional Art: The Emergence of New Photographic art in the Post-Stalin Soviet Union

“Unconventional Art: The Emergence of New Photographic art in the Post-Stalin Soviet Union.” Paper presented at the SECAC (South Eastern College Art) annual conference Collisions: Where Past Meets Present, Meredith College, Durham, NC, October 17–20, 2012.

In this paper I explore photography as a new and unconventional art emerging in the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death in 1953, during the period often called the Khrushchev’s Thaw. I discuss the paradox that this art appears surprisingly apolitical, seemingly socially passive, and escapist, but at the same time this passivity in some cases functioned as an active political position, or at least as a statement of a certain level of artistic freedom in the given political circumstances.

I also introduce some major difficulties of analysis and interpretation of this art from the perspective of western canon of art history and photography, which can easily accommodate the Soviet avant-garde photography of the 1920s and early 1930s, but which has no place for later, postwar developments that do not follow the historical narrative of advanced practice of photography in the western culture.