"The Misunderstood 'Universal Language' of Photography: The Fourth FIAP Biennial, 1956." Paper presented at the conference Art, Institutions, and Internationalism: 1933–1966 in New York City, March 7, 2017.

Read moreThe Selfie: More and Less than a Self-Portrait (New York, 2016)

"The Selfie: More and Less than a Self-Portrait," an invited talk at the symposium What Now? 2016: On Future Identities, organized by Art in General in collaboration with the Vera List Center for Art and Politics (May 20-21, 2016). New York City, May 21, 2016.

Download symposium booklet PDF and view the video recordings of all talks and panel discussions on Art in General web site here.

I am very grateful to Anne Barlow, director of Art in General, for inviting me to be part of this exciting symposium.

My talk was included in the panel "Technology and Presentations of the Self," excellently moderated by Soyoung Yoon. I had the pleasure to discuss my research with two inspiring co-panelists, Daniel Bejar and Sondra Perry. We were joined by Evan Malater.

I am thankful to Carin Kuoni, director of Vera List Center for Art and Politics, for co-organizing and hosting the symposium. I wish to thank also Kristen Chappa and Lindsey Berfond of Art in General for making this happen.

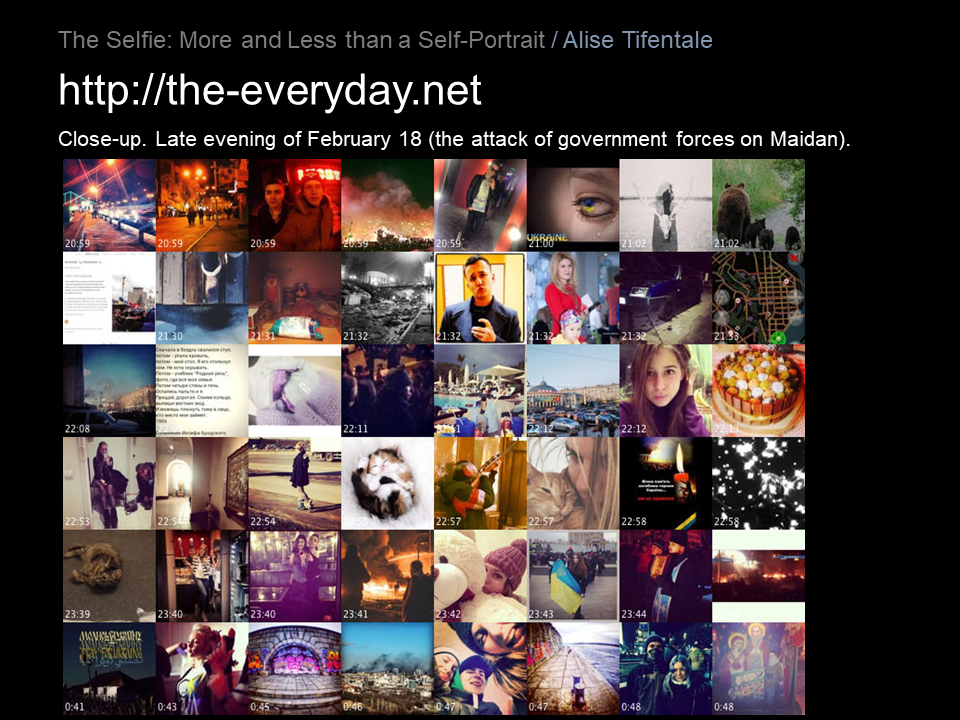

My talk was based on a critical revision of some of the methods and findings of my co-authored research projects on social media photography such as Selfiecity (2014), Selfiecity London (2015), and The Exceptional and the Everyday: 144 Hours in Kyiv (2014) as well as subsequent research articles written by me or co-written with Lev Manovich.

See a short summary of the talk on the news section of this web site.

For a theoretical background, see my article "The Networked Camera at Work: Why Every Self-portrait Is Not a Selfie, but Every Selfie is a Photograph" published in the catalog of the 2016 Riga Photography Biennial.

Excerpt of the talk:

Selfies belong to what Vilém Flusser calls the universe of technical images. As such, these images have functions and characteristics that are different from traditional images such as paintings or drawings.

According to Flusser, the traditional images were observations of objects, whereas the technical images always are computations of concepts.

It follows that the technical images are not reproductive but rather they are productive. In other words, technical images are not a mirror of reality, but rather a projection, a constructed and produced image.

Therefore we could say that selfies are tools of production or construction of a self, rather than a representation of a pre-existing self.

Then what do selfies mean?

But to ask, what any photograph - a technical image - means, “is an incorrectly formulated question,” Flusser wrote in his book Into the Universe of Technical Images. “Although they appear to do so, technical images don’t depict anything: they project something. To decode a technical image is not to decode what it shows but to read how it is programmed.”

And furthermore, “We must criticize technical images on the basis of their program. Criticism of technical image requires analysis of their trajectory and analysis of the intention behind it. This is because technical images don’t signify anything: they indicate a direction.”

I would argue that the direction that selfies indicate is more away from reflection of the self in an art-historical sense and more towards the interaction with the apparatus of image-making and image-sharing which includes not only the image, but also the devices and software.

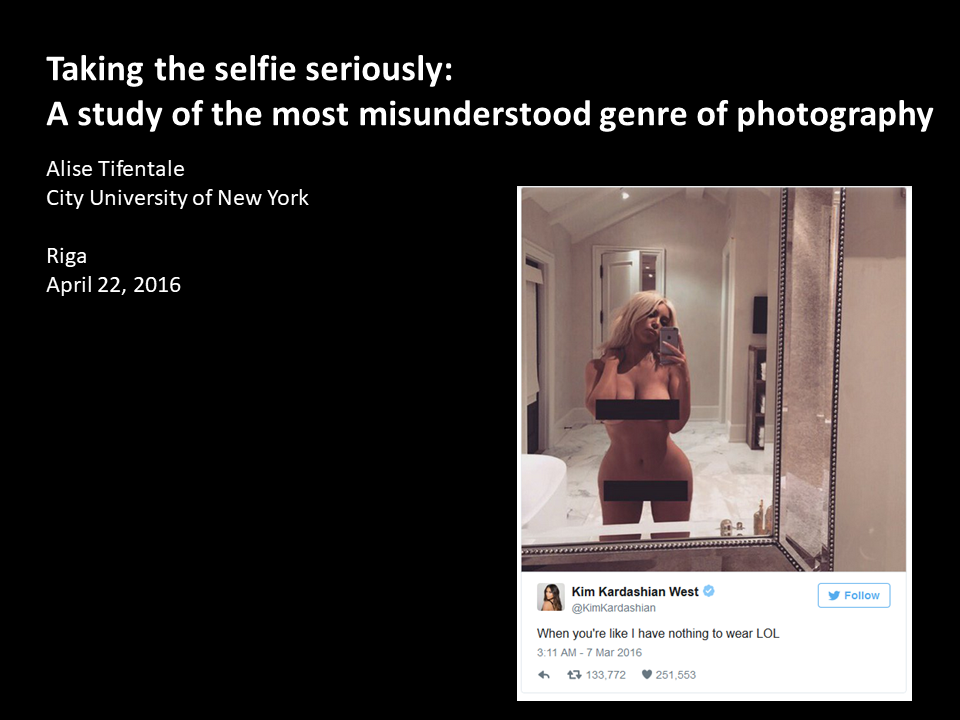

Taking the Selfie Seriously: A Study of the Most Misunderstood Genre of Photography (Riga, 2016)

"Taking the Selfie Seriously: A Study of the Most Misunderstood Genre of Photography," an invited talk at the Riga Photography Biennial symposium "Image and Photography in the Post-Digital Era" (April 22-23, 2016), Riga, Latvia, April 22, 2016. Symposium was organized by curator and art historian Maija Rudovska.

The talk was based on some of the methods and findings of the research project Selfiecity.net (2014) and subsequent research articles written by me or co-written with Lev Manovich.

For a further elaboration of the arguments proposed in the talk, see also my article "The Networked Camera at Work: Why Every Self-portrait Is Not a Selfie, but Every Selfie is a Photograph" published in the catalog of the Riga Photography Biennial.

The talk argued against the marginalization of the selfie as a notorious and outrageous kind of photography produced by reality TV stars and other celebrities as well as immature and psychologically unstable teenagers.

The findings of Selfiecity showed that some of the popular assumptions about the selfie are not true, and emphasized the diversity and cultural difference that can be communicated via this genre of popular photography.

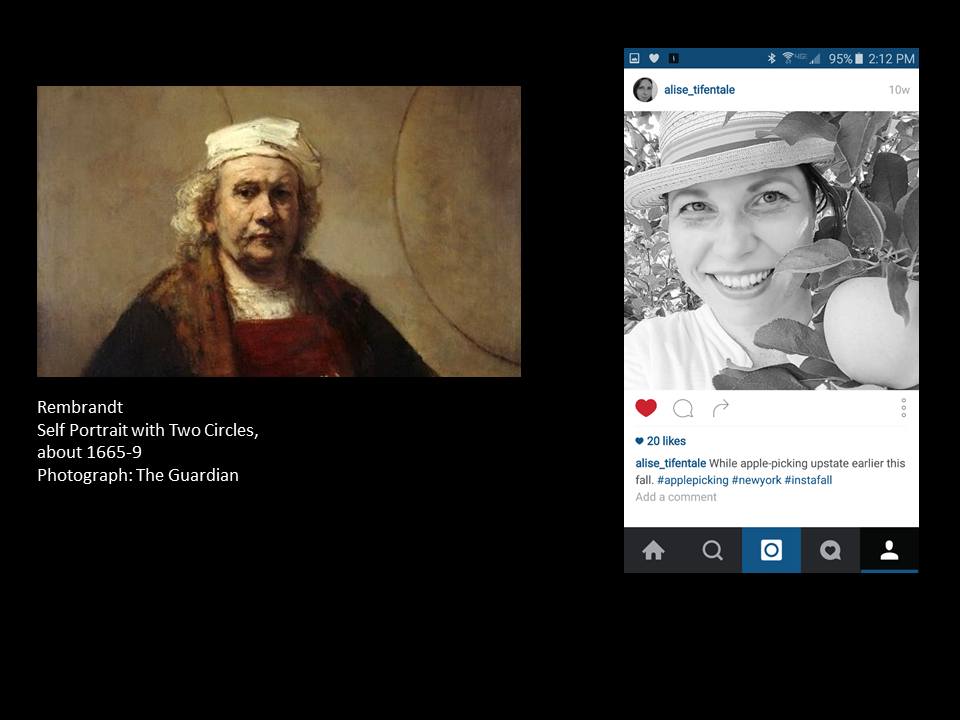

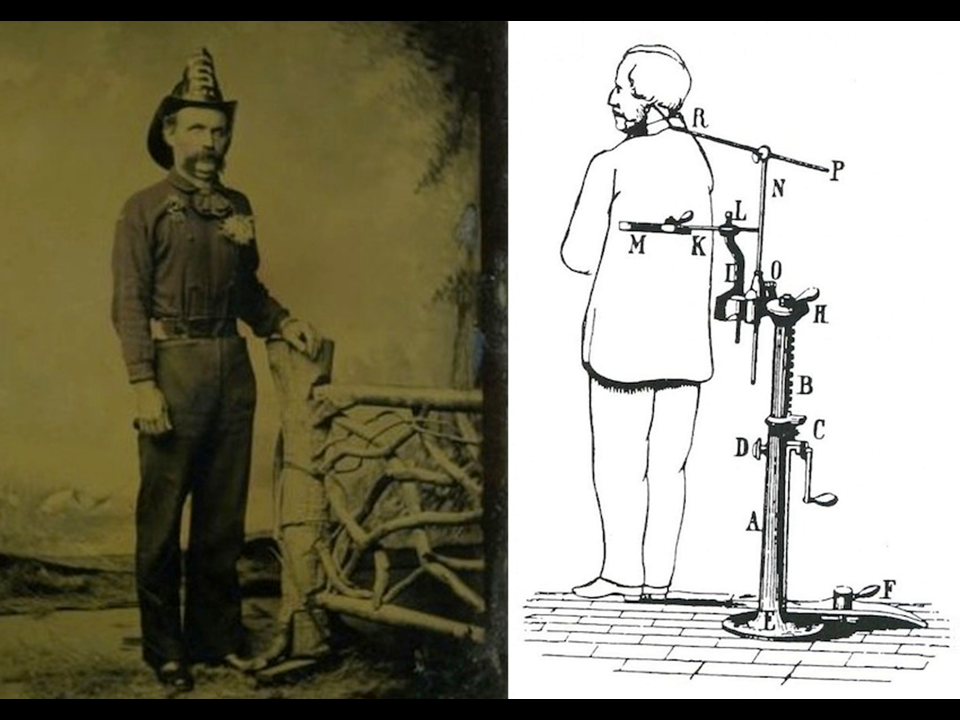

Furthermore, the talk pointed to the two extremes of presentism in the popular discourse about the selfie: one describes this genre as something unprecedented and unique, whereas the other attempts to directly compare today's selfies to, for example, the painted self-portraits of the artists of the Renaissance. Both of these approaches lack methodological clarity and seem to overlook the historical specificity of the selfie and the particular cultural context in which this genre exists.

These popular misconceptions about the selfie at times make it complicated to view the selfie as just one of the many sub-genres of popular photography. This talk offered an alternative approach and discussed the benefits and limitations of combining computational analysis with humanities methods in order to make sense of the selfie.

Art and Communism: A Love-Hate Relationship (New York, 2015)

"Art and Communism: A Love-Hate Relationship," a guided tour in the exhibition Specters of Communism: Contemporary Russian Art, curated by Boris Groys (February 6 – March 28, 2015), at The James Gallery, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, New York. March 3, 2015.

People who have experienced communism tend to dislike it. People who have not experienced it tend to like it. This tour will trace the ‘specter’ of communism in the works on view, while also engaging in a broader discussion of the complex legacy of Karl Marx’s original observations about nineteenth-century Manchester. The spirit of communism was responsible for many contradictory events: it inspired the historical Russian avant-garde, supported the oppressive regime of Stalin, fascinated the students of Sorbonne in 1968, and supported Mao’s Cultural Revolution. Together we will practice Marxist dialectics in order to consider both sides of this ‘specter’.

Avant-Garde in a Cottage Kitchen: Photographs by Zenta Dzividzinska from the 1960s (Malmö, 2014)

"Avant-Garde in a Cottage Kitchen: Photographs by Latvian artist Zenta Dzividzinska from the 1960s," The Moderna Museet, Malmö, Sweden, November 20, 2014.

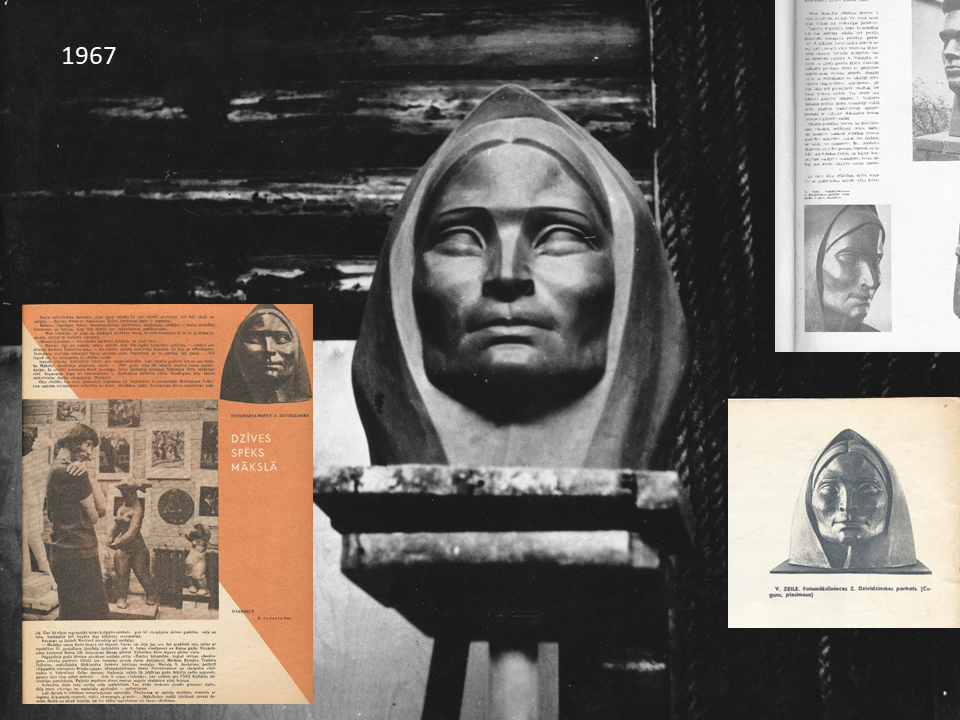

Invited speaker on the occasion of a contemporary art exhibition Society Acts (September 20, 2014 - January 25, 2015), The Moderna Museet, Malmö, Sweden. Co-curator of the exhibition, Maija Rudovska, had included in the show a selection of photographs by Latvian artist Zenta Dzividzinska. My talk was aimed at introducing the Swedish public to the artist's oeuvre and the broader context of Latvian photography in the 1960s.

Read more about the exhibition concept on E-Flux.

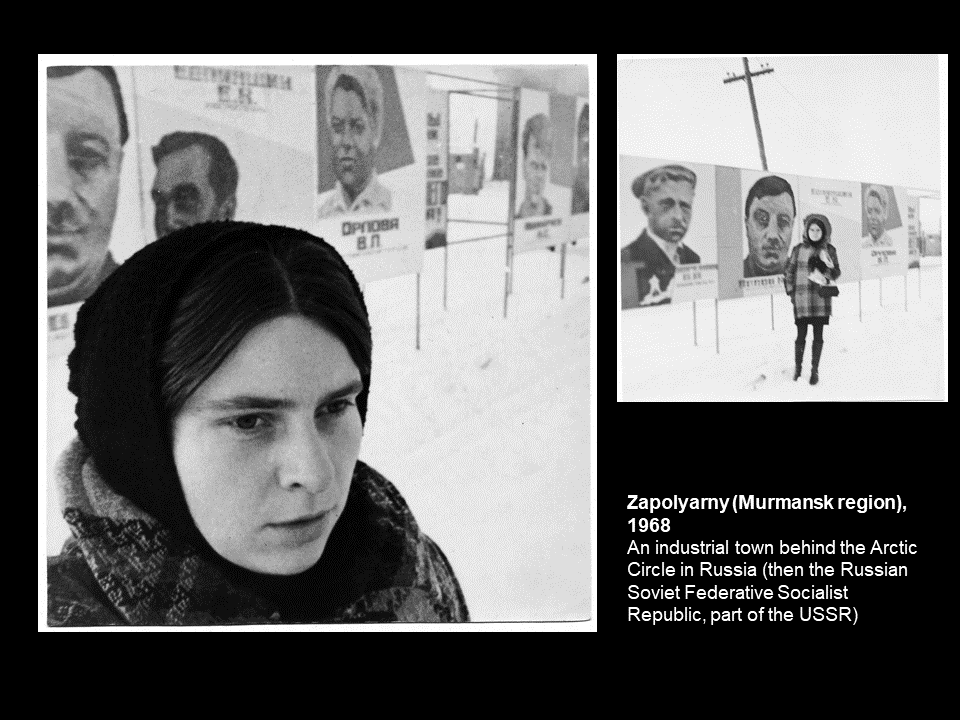

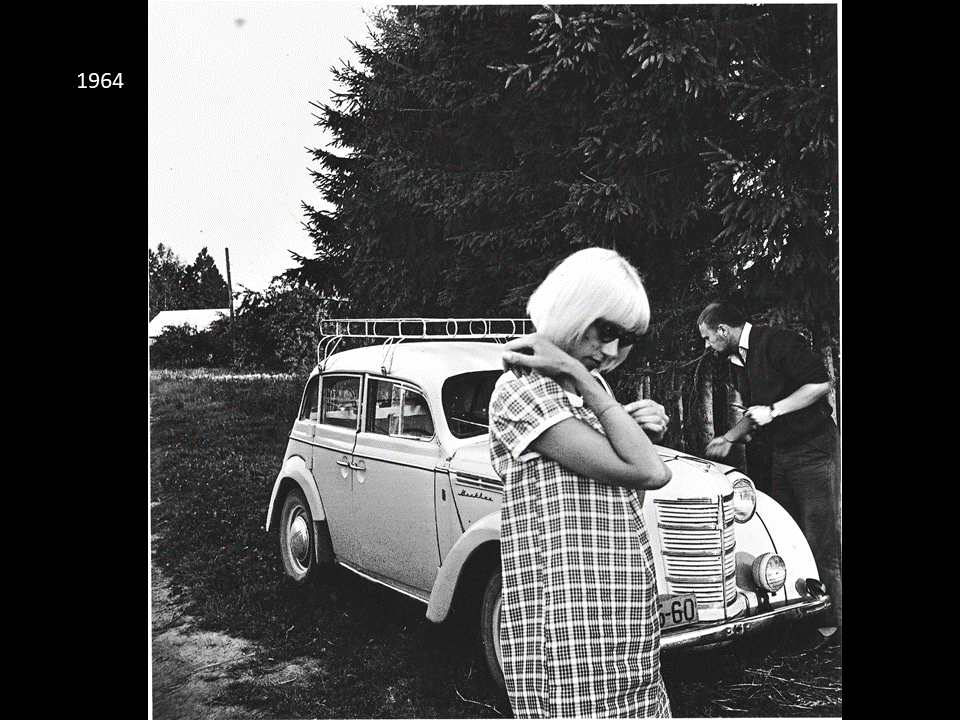

The talk presents the extraordinary life and artistic career of Latvian artist Zenta Dzividzinska (1944-2011), focusing on her artistic output of the 1960s. Her choices were untypical and unconventional for the art world under the Soviets, and her works have remained relatively invisible even now. She chose photography as her major medium in time when photography was not considered a "real" art. Being almost the only woman in the competitive and patriarchal circle of unofficial art photographers in Riga, she succeeded in gaining their respect while still in her early twenties.

Alise Tifentale presenting the talk. Photo: hon Sun Lam.

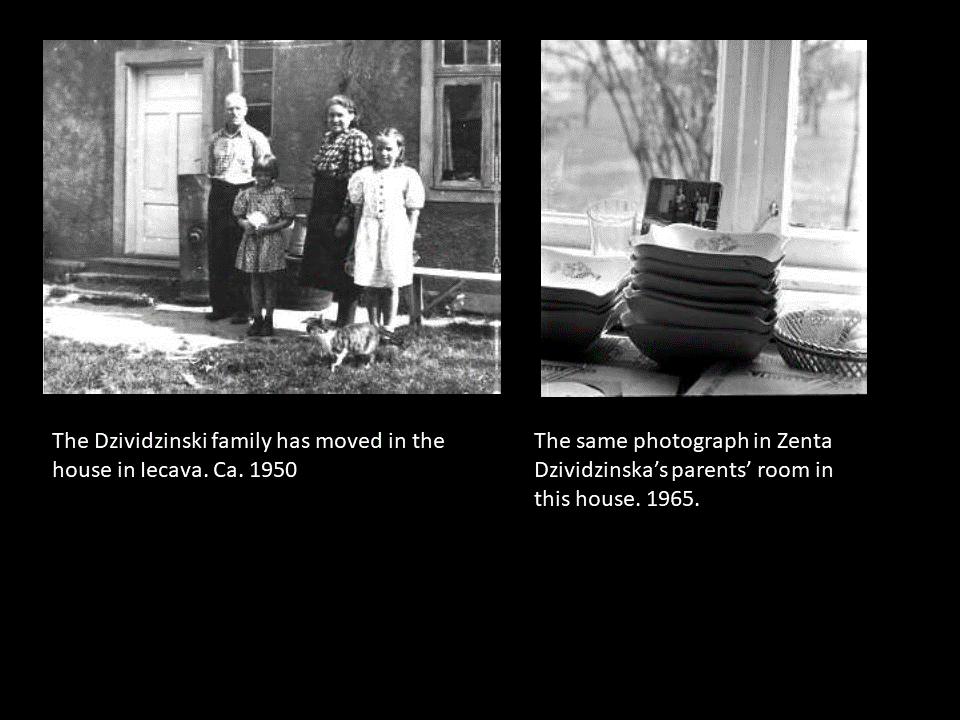

However, her favorite subject - photographic depiction of everyday life in a country house featuring members of her extended family - was regarded as unsightly and ridiculous, thus most of her work has remained unpublished even now. That’s also where the cottage kitchen in the title of the talk comes from – that’s her parents’ little house in countryside, a village called Iecava in Southern part of Latvia. Even though she was educated in art school in the capital city Riga, and all the art world was happening in Riga, and all the jobs were there, most of the time Dzividzinska resided there and commuted to Riga. The small and cramped kitchen was a makeshift darkroom for her photographic work.

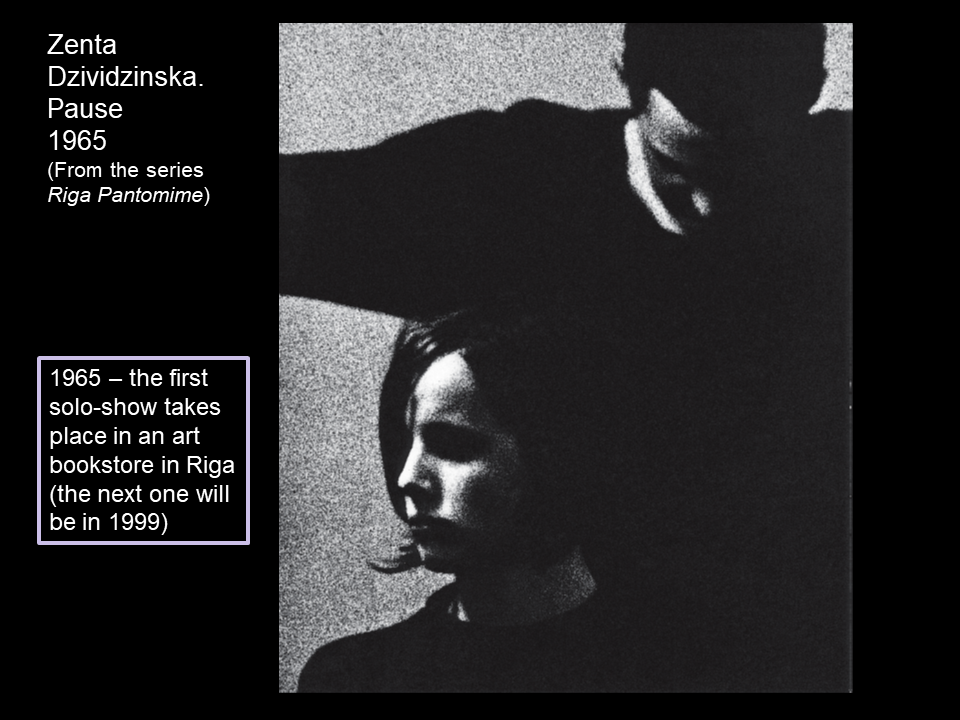

What understood meant by the word “avant-garde” in the title – in this case, I use the term to describe a radical practice, something that is ahead of time, a practice that is still to be understood by the public much later. Despite her being acknowledged as one of the leading fine art photographers in the late 1960s, during this decade Dzividzinska had only one solo-show – in 1965, in an art bookstore in Riga. Her next (and last) solo-show followed in 1999.

Women at Work: Artistic Production, Gender, and Politics in Russian Art and Visual Culture (Riga, 2014)

"Women at Work: Artistic Production, Gender, and Politics in Russian Art and Visual Culture," Contemporary Art Center Kim?, Riga, Latvia, June 12, 2014.

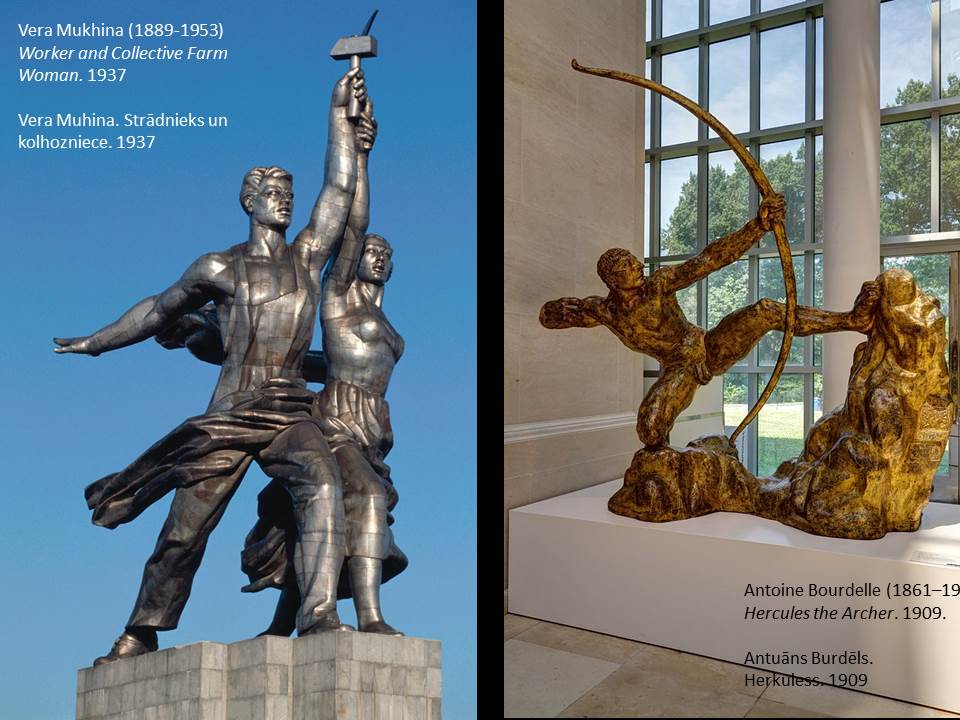

Invited speaker (together with Dr. Cristina Kiaer) on the occasion of a contemporary art exhibition Little Vera, dedicated to the 125th anniversary of the Riga-born Russian artist Vera Mukhina (1889-1953). The exhibition was organized by curator Zane Onckule at the contemporary art center Kim? in Riga, Latvia.

Artists in the exhibition: Ella Kruglyanskaya and Sanya Kantarovsky. View more installation shots of the exhibition.

Excerpt from the talk:

As part of my larger research project dealing with women as image makers and images of women in the twentieth century, I am investigating the relationships between labor and its representation in art and visual culture in the late Imperial Russia and early Soviet Union. My research, which focuses on photography but is not limited to it, also raises questions regarding art historical methodologies and terminology, as very often the standard tools and methods of western art history and criticism are not directly applicable to art and visual culture produced in the Soviet Union.

Art historian Jo Anna Isaak was one of the first scholars in the early 1990s who opened up a discussion about application of western feminist critique to Soviet art and who tried to find out why and how Soviet “feminism” or women’s emancipation movement was different from its Western counterpart, and why later Western feminist movement ideas did not gain any popularity among the Russian / Soviet / post-Soviet artists.

For example, Isaak looks back at the Russian history of the 19th century and argues that one of the reasons why the ideas of Roszika Parker and Griselda Pollock about the artist and woman as marginalized figures in the Western bourgeois society are not relevant when we look at the same time period in Russia, is the fact that there was no such bourgeoisie in the first place.

Latvian Art Talk. Just what is it that makes Latvian art so different, so Latvian? (New York, 2013)

Just what is it that makes Latvian art so different, so Latvian? A talk on Latvian contemporary art at Art in General, New York, May 4, 2013. Read more on Art in General web site: http://www.artingeneral.org/exhibitions/548

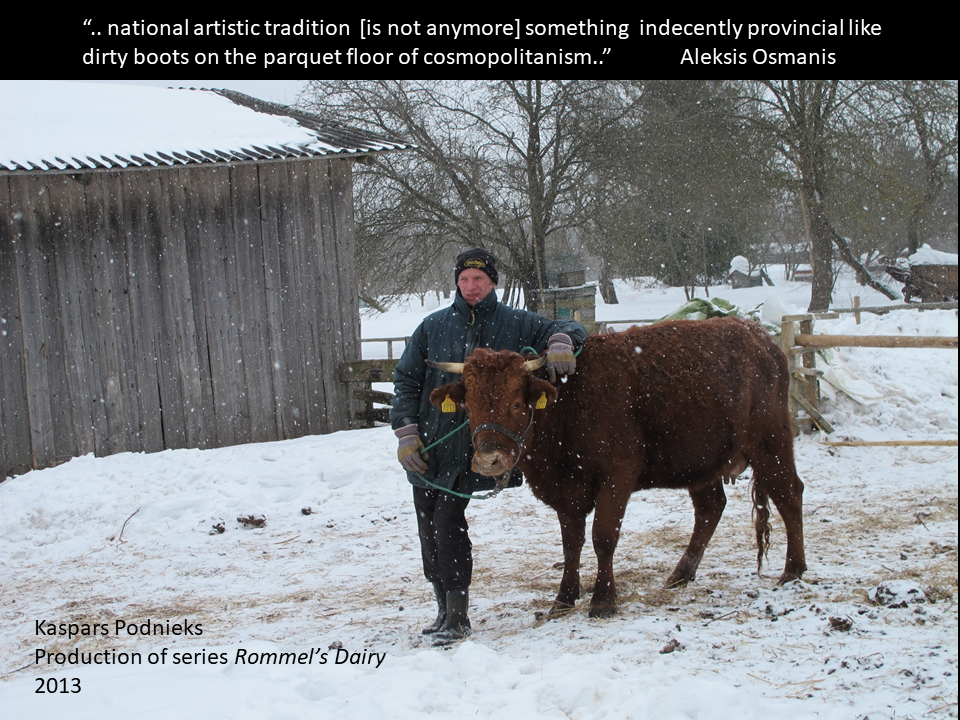

As a co-curator (together with Anne Barlow and Courtenay Finn) of North by Northeast, the Latvian Pavilion for the 55th Venice Biennale, I am honored to present the pavilion and the artists, Kaspars Podnieks and Krišs Salmanis, in New York. The talk is part of the pre-biennale presentation of North by Northeast which includes also an exhibition of Podnieks’ and Salmanis’ work in the storefront Project Space of Art in General (March 5 – March 30, 2013).

Works by Latvian contemporary artists Kaspars Podnieks and Krišs Salmanis question the identity of a nation that has to grapple with its always marginal position in the politicized geography of Europe. Under the Soviet rule, Latvia was the westernmost borderland of the Soviet Union. The point of reference radically shifted after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, when Latvia regained its independence and paradoxically found itself on the north-eastern most border of the European Union. The ideological implications of this changing and always imaginary political geography provoke insecurity and doubt in terms of self-fashioning: what does it mean to be a Latvian artist or a Latvian in general? Is it the patriarchal rural lifestyle, appreciation of local landscape as a redemptive Arcadia, self-imposed laws of merciless work ethic, or traditional oppression of any socially or politically explicit thought? Or rather searching for an escape route from all of it?

Read my essay Just what is it that makes Latvian art so different, so Latvian? in the catalogue of North by Northeast, the Pavilion of Latvia in the 55th Venice Biennale (2013).

View the slides from the talk here:

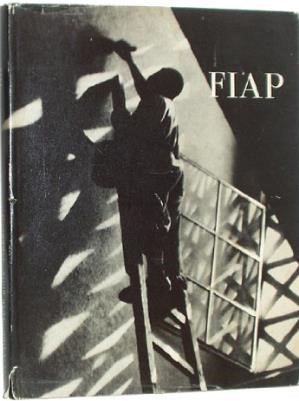

The 'Cosmopolitan Art': The FIAP Yearbooks of Photography, 1954–60

“The ‘Cosmopolitan Art:’ The FIAP Yearbooks of Photography, 1954–60.”

Paper presented at the 105th Annual CAA Conference, New York City, February 17, 2017.

Photo: Elizabeth Cronin.

“It is a diversified, yet tempered picture book containing surprises on every page, a mirror to pulsating life, a rich fragment of cosmopolitan art, a pleasure ground of phantasy”—this is how, in March 1956, the editorial board of Camera magazine introduced the latest photography yearbook by the International Federation of Photographic Art (Fédération internationale de l'art photographique, FIAP). This paper will analyze this “cosmopolitan art” of photography in the first four FIAP yearbooks, published between 1954 and 1960 on a biennial basis.

FIAP, a nongovernmental transnational organization, was founded in Switzerland in 1950 and aimed at uniting the world’s photographers. Its members were national associations of photographers, representing 55 countries: seventeen in Western Europe, thirteen in Asia, ten in Latin America, six in Eastern Europe, four in Middle East, three in Africa, one in North America, and Australia. Photographs for FIAP yearbooks were selected from works submitted by all member associations.

The resulting large format hardcover photo-books consisted of average 120 full-page photogravure reproductions, grouped by country. These yearbooks, I argue, complicated and politicized the understanding of photographic art in the 1950s. On one side, the yearbooks presented a groundbreaking attempt to reject Western Europe as the only center of creativity in favor of a model of global participation. On the other, the organization’s ambition to survey the cultural diversity of the world at times was limited by ethnographic stereotyping (e.g., recurring depictions of Catholic priests or nuns in the Spanish section or portraits of geishas from Japan).

This paper was part of the panel "Photography in Print," moderated by Andrés Mario Zervigón, Rutgers University. The two other presenters in our panel were C.C. Marsh, The University of Texas at Austin, who presented Between Art and Propaganda: Photo-Monde in the Service of the UN, and Meredith TeGrotenhuis Shimizu, Whitworth University, who presented The Spectacularization of Disaster: Photographs of Destruction in Commemorative Coffee Table Books.

Thank you to all who came to our panel. It was a great honor to present my research and discuss it with the two other scholars in our panel.

The panel "Photography in Print" at the CAA 2017. From the left: Meredith TeGrotenhuis Shimizu, C.C. Marsh, and Alise Tifentale.

Exhibition review: "Anri Sala: Answer Me" at the New Museum, New York

A review of the exhibition Anri Sala: Answer Me at the New Museum, 2016, commissioned by the CAA.Reviews.

Read moreRules of the Photographers’ Universe

“Rules of the Photographers’ Universe,” Photoresearcher (journal of the European Society for the History of Photography), No. 27 (April 2017), pp.68-77. Special issue "Playing the Photograph," edited by guest editors Matthias Gründig and Steffen Siegel.

Read morePhotography in Latvia, 1970–2000

“Photography in Latvia, 1970–2000,” in The History of European Photography 1970–2000 (vol. 3) (Bratislava: Central European House of Photography, 2017). ISBN 9788085739701.

Read moreThe Selfie: More and Less than a Self-Portrait

“The Selfie: More and Less than a Self-Portrait,” in Moritz Neumüller, ed., Routledge Companion to Photography and Visual Culture (London, New York: Routledge, 2018), 44–58.

Read moreCompetitive Photography and the Presentation of the Self

Alise Tifentale and Lev Manovich, "Competitive Photography and the Presentation of the Self" in Jens Ruchatz, Sabine Wirth, and Julia Eckel, eds., Exploring the Selfie: Historical, Analytical, and Theoretical Approaches to Digital Self-Photography (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 167-187.

Read morePhotography: Taken, not Made

"Photography: Taken, not Made," in Arnis Balčus, ed., Territories, Borders, and Checkpoints (Riga Photomonth Catalogue) (Riga: Society Riga Photomonth, 2016), pp. 90-95. ISBN 978-9934-14-852-1.

The essay accompanied an exhibition of experimental photography, Paintings and Sculptures, curated by Arnis Balčus and Elīna Sproģe as part of Riga Photomonth programming. The artists in the exhibition: Eduards Gaiķis, Valters Jānis Ezeriņš, and Līga Spunde. The exhibition took place at the Exhibition hall of the Latvian National Library, Riga, May 7-30, 2016.

Read moreThe Networked Camera at Work: Why Every Self-Portrait Is Not a Selfie, but Every Selfie is a Photograph

"The Networked Camera at Work: Why Every Self-Portrait Is Not a Selfie, but Every Selfie is a Photograph," in Santa Mičule, ed., Riga Photography Biennial 2016 (Riga: Riga Photography Biennial, 2016), 74-83. ISBN 9789934148613.

This article focuses on the role of technologies in defining and understanding the selfie. While there is danger of slipping into oversimplified technological determinism, we have to admit that the role of technologies in visual culture, and especially photography, is often underestimated. Could phenomena like the selfie really be just a byproduct of the advancement and accessibility of digital image-making and image-sharing technologies? Or rather new and emerging photographic practices shape the design and features of hardware and apps, such as the introduction of the camera (and then the second one) in smartphones and appearance of Instagram and other image-sharing platforms? In this article, I examine the difference between the way datasets of selfies are being constructed for research and comparison, and how selfies are consumed and experienced in their natural habitat, the live flow of images on Instagram.

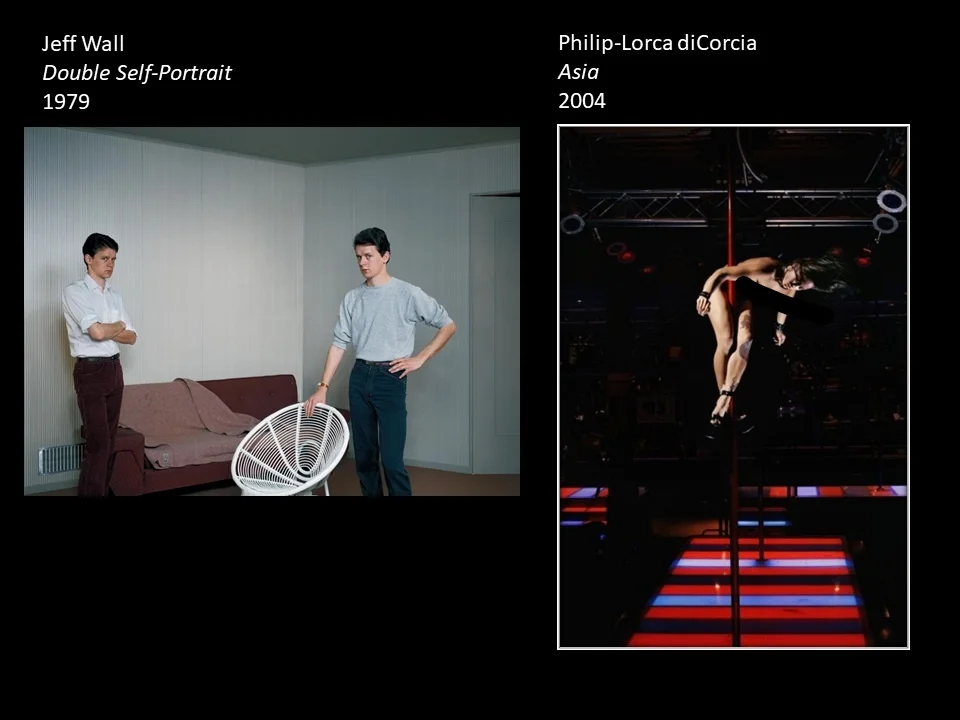

Recently an artist friend claimed in a conversation that he thinks that people, including himself, have made “selfies” all the time, even before the appearance of social media and smartphones. He said he used the word “selfie” just as a shorter version of “self-portrait.” Indeed, “selfie” is closely related to the concept of “self-portrait,” but it is more than that.

Looking back into the history of photography, the cheap and easy to use Kodak Brownie cameras around 1900 gave rise to popular and amateur photography, introduced the snapshot, and established a tradition of family photograph albums. Similarly, around 2010 we saw a rise of a new kind of image-making device, the smartphone with a built-in camera and wireless connection to the Internet. Availability of such devices on mass market was followed by a formation of new sub-genres of popular photography, such as the selfie.

This, however, could happen only because a demand or desire for such technological innovations had already been articulated in society. Thus also the appearance of the selfie as a new sub-genre of popular photography is historically time-specific: it could emerge only in a moment when several technologies have reached a certain level of development and accessibility and when a “burning” human desire had emerged, referring to Geoffrey Batchen’s highly influential book (Burning with Desire: The Conception of Photography (Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 1997)). Although many photographers—well-known artists and enthusiastic hobbyists alike—have made self-portraits since the very early days of photography, scholars have confirmed that “self-portraits did not become a mundane practice until the digital camera converged with the mobile phone" (Marika Lüders, Lin Prøitz, and Terje Rasmussen, "Emerging Personal Media Genres," New Media & Society 12, No. 6 (2010): 959).

Furthermore, the convergence of the camera with smartphone is not all that is needed for a selfie—there has to be a human desire to make such picture and—equally important—to share it with one’s peers. According to the definition by the Oxford Dictionaries, a selfie is “…a photograph that one has taken of oneself, typically one taken with a smartphone or webcam and shared via social media.” This definition neatly sums up all three key activities that are essential for the selfie: taking a photographic image of oneself, using a camera on one’s smartphone, and sharing this image on social media networks. While other scholars have introduced the term “networked image,” I would like to suggest a slightly different term that shifts the focus more toward the apparatus that produces the image: the networked camera.

The networked camera is a curious hybrid: an image-making, image-sharing, and image-viewing device whose necessary features include hardware such as easy to use smartphone with a built-in camera, the availability of wireless Internet connection, the existence of online image-sharing platforms, and the corresponding software, the ‘invisible hand’ that drives the devices and service platforms. This combination facilitates a streamlined production, dissemination, and consumption of visual information.

The concept of the networked camera helps to understand the selfie as a hybrid phenomenon that merges the aesthetics of photographic self-portraiture with the social functions of online interpersonal communication. Already before Instagram and the selfie, some scholars had noted the dualism of online image-sharing practices—the coexistence of their aesthetic and social functions—and had observed that the emphasis in analysis most often tends to be put on the “social life of the networked image”, while overlooking the image itself (see, for example, Daniel Rubinstein and Katrina Sluis, “A Life More Photographic, Mapping the Networked Image,” Photographies 1, No. 1 (2008), 9-28). Social sciences and media studies indeed provide a solid theoretical and methodological basis for thinking about identity construction and performance in social network sites (see, for example, Zizi Papacharissi, ed., A Networked Self: Identity, Community and Culture on Social Network Sites (New York: Routledge, 2011)). Our task remains to re-connect the medium with the message and aesthetics with functionality.

Just like the networked camera is more than only a new type of camera, the selfie is more than an image. Although the selfie is reminiscent of traditional photographic self-portraiture, its other essential attributes include metadata, consisting of several layers: automatically generated data (like geo-tags and time stamps), data added by the user (hashtags), and data added by other users (comments). Another, no less important attribute of the selfie is the instantaneous dissemination of the image via Instagram or similar social networks that makes the selfie significantly different from its earlier photographic precursors (see Kandice Rawlings, “Selfies and the History of Self-Portrait Photography,” November 21, 2013). As Sonja Vivienne and Jean Burgess have observed, “much more important than digital photography’s influence on the practice of taking photographs, then, are the ways in which the web has changed how and what it means to share photographs" (Vivienne and Burgess, “The Remediation of the Personal Photograph and the Politics of Self-Representation in Digital Storytelling,” Journal of Material Culture 18, No. 3 (2013), 281. Emphasis in original).

These considerations can partly serve as an answer to those who tend to apply the term “selfie” retroactively to photographic self-portraits made before c. 2010. While there are lots of self-portraits in the history of photography that look seemingly similar to selfies—self-portraits in mirrors, self-portraits made while holding the camera in one’s extended arm etc.—these images are not selfies because they are not products of the networked camera, they were not made with a camera of one’s smartphone and were not shared on social media networks. As simple as that.

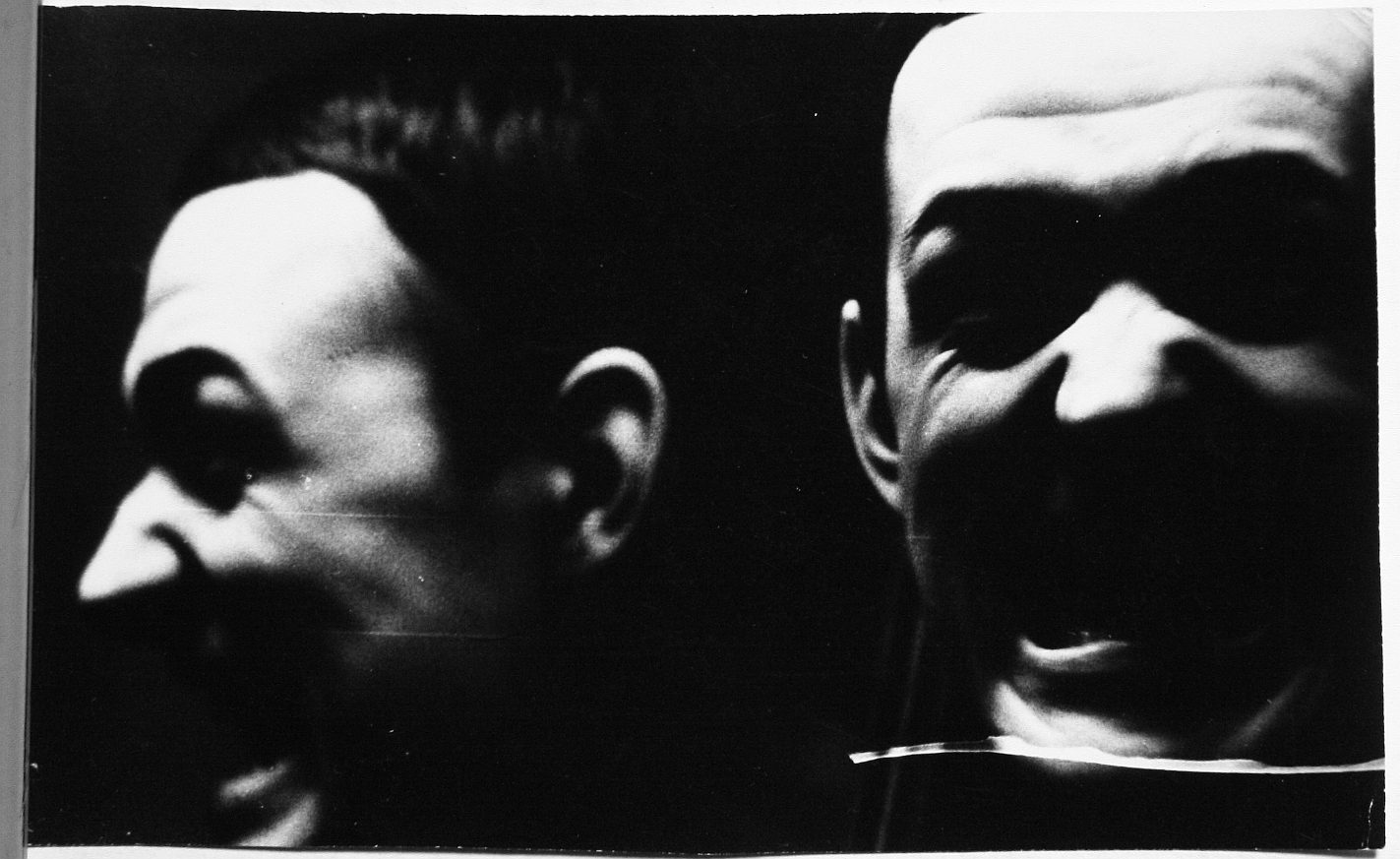

The Impossibility of Capturing Butoh in Photography

“Neiespējamais butō tulkojums fotogrāfijā [The Impossibility of Capturing Butoh in Photography],” in Simona Orinska, ed., Butoh (Riga: Mansards, 2015), 68-79. In Latvian only. ISBN 9789934121098. Available from the publisher's website.

I’m grateful to Simona Orinska, the editor of this book and a butoh artist, for inviting me to contribute to this volume and to think about such a challenging topic.

Since 2011, when Orinska conceived the idea of the book and solicited the first drafts of the articles, I’ve had many chances to return to the topic and ask myself, how can I describe the relationships between butoh, a performance based on movement and emotion, and photography, a medium that freezes movement and removes all emotions?

To address this question, in this article I revisit theoretical writings about the depiction of movement and dance in photography. I introduce a comparative reading of Kamaitachi (1968), a well-known series of photographs by Japanese photographer, Eikoh Hosoe (b. 1933), and Riga Pantomime (1964-1965), an almost unknown series by Latvian photographer and artist, Zenta Dzividzinska (1944-2011).

This comparison brings to the fore a similarly heightened expressiveness of human body and face that photographers captured in two different cultures: in butoh of the postwar Japan and pantomime in Latvia under the oppressive Soviet regime. Can there be two more different cultures as these? But a totally unexpected meeting point of these cultures appears in a photograph by Zenta Dzividzinska, Hiroshima (1964-1965), taken at a rehearsal of eponymous performance by pantomime troupe Riga Pantomime.

See below more photographs by Zenta Dzividzinska from the series Riga Pantomime (1964-1965). Most of the photographs from this series were never exhibited during the artist's lifetime, but a small selection of vintage prints recently was included in the exhibition Society Acts (September 20, 2014 - January 25, 2015) at the Moderna Museet, Malmö, Sweden. Read more about this exhibition and my short presentation of Dzividzinska's works at the Moderna Museet.

Steichen, The Artist and Propagandist

"The Artist and Propagandist: Steichen's Role at Two Decisive Moments in the History of American Photography," in Šelda Puķīte, ed., Edward Steichen. Photography (Riga: Latvian National Museum of Art, 2015), 33-37. ISBN 9789934512575. Published on the occasion of exhibition "Edward Steichen. Photography" at the Latvian National Museum of Art, The Arsenals Exhibition Hall, Riga, Latvia, June 26 – September 6, 2015.

Edward Steichen’s name is associated with the emergence of two aesthetically and thematically different and even oppositely oriented movements in photography. At the beginning of the 20th century Steichen was a pioneer of Pictorialism, and his 1904 photograph The Pond-Moonlight is a textbook example of this artistic style: intimate, romantic, timeless, and painterly.

Yet in the middle of the 20th century Steichen became a master of American political propaganda in photography and remains known for the creation of a radically new and different type of photography exhibition. In Steichen’s curated photography exhibitions, Road to Victory (1942) and The Family of Man (1955) at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, photographs lost their individuality, and the participating photographers’ original intentions were sacrificed for the sake of creating an atmosphere of patriotic pathos.

This article examines “Steichen the Pictorialist” and “Steichen the Curator,” the two contradictory directions in Steichen’s career and their interpretations by art historians in order to establish a broader context for the work on view in the current exhibition.

Selfiecity: Exploring Photography and Self-Fashioning in Social Media

“Selfiecity: Exploring Photography and Self-Fashioning in Social Media” (co-author Lev Manovich), in David M. Berry and Michael Dieter, eds., Postdigital Aesthetics: Art, Computation and Design (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 109-122. ISBN 9781137437198.

NB: This is unedited working draft. Please refer to the book for the final published version of this chapter.

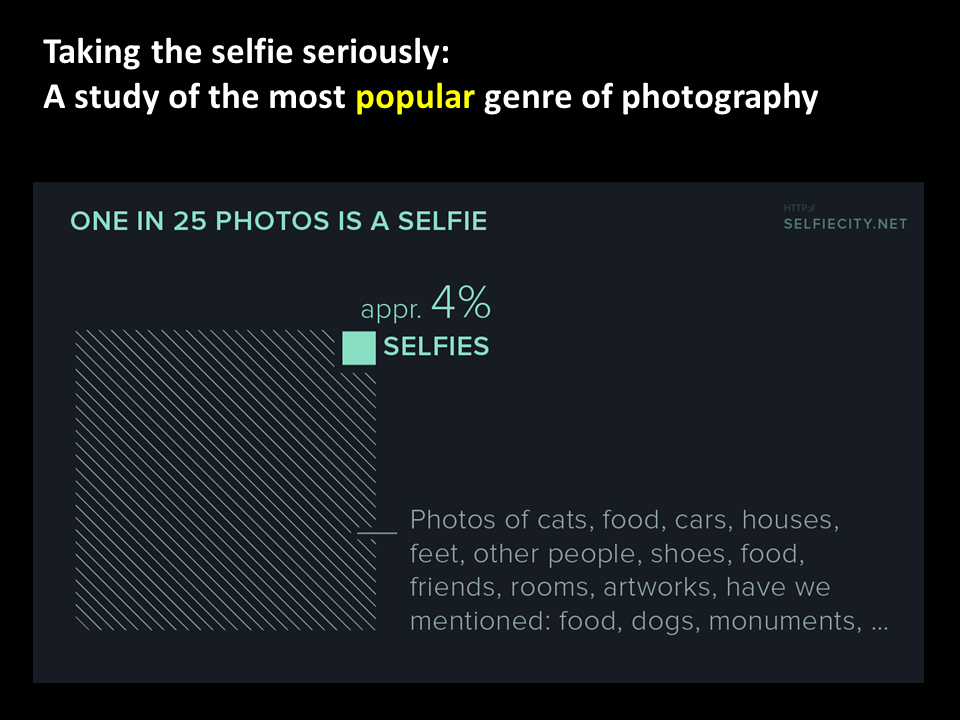

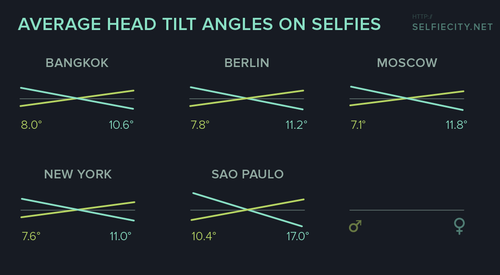

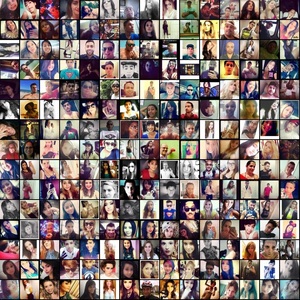

This chapter summarizes the methods and findings of the research project Selfiecity (2014).

User-generated visual media such as images and video shared on Instagram, YouTube, and Flickr open up fascinating opportunities for the study of digital visual culture and thinking about the postdigital. Since 2012, the research lab led by Lev Manovich (Software Studies Initiative, softwarestudies.com) has used computational and data visualization methods to analyze large numbers of Instagram photos. In our first project Phototrails, we analyzed and visualized 2.3 million Instagram photos shared by hundreds of thousands of people in 13 global cities.

Given that everybody is using the same Instagram app, with the same set of filters and image correction controls, and even the same image square size, and that users can learn from each other what kinds of subjects get most attention, how much variance between the cities do we find? Are networked apps such as Instagram creating a new universal visual language which erases local specifities? Does the ease of capturing, editing and sharing photos lead to more aesthetic diversity? Or does it, instead, lead to more repetition, uniformity and visual social mimicry, as food, cats, selfies, and other popular subjects drown everything else out?

In our project we wanted to show that no single interpetation of the selfie phenomenon is correct by itself. Instead, we wanted to reveal some of the inherent complexities of understanding the selfie – both as a product of the advancement of digital image making and online image sharing and a social phenomenon that can serve many functions (individual self-expression, communication, etc.).

By analyzing a large sample of selfies taken in specified geographical locations during the same time period, we argue that we can see beyond the individual agendas and outliers (such as the notorious celebrity selfies) and instead notice larger patterns, which sometimes contradict popular assumptions.

For example, considering all the media attention selfie has received since late 2013, it can easily be assumed that selfies must make up a significant part of images shared on Instagram. Paradoxically enough, our research revealed that only approximately four percent of all photographs posted on Instagram during one week were single person selfies.

Art of the Masses: From Kodak Brownie to Instagram

“Art of the Masses: From Kodak Brownie to Instagram,” Networking Knowledge 8, No. 6 (2015). Special issue “Be Your Selfie: Identity, Aesthetics and Power in Digital Self-Representation,” edited by Laura Busetta and Valerio Coladonato.

Read moreMaking Sense of the Selfie: Digital Image-Making and Image-Sharing in Social Media

“Making Sense of the Selfie: Digital Image-Making and Image-Sharing in Social Media,” Scriptus Manet 1, No. 1 (2015): 47–59. ISSN: 2256-0564.

The article addresses digital photographic self-portraiture in social media (so-called selfies) as an emerging sub-genre of amateur photography. The article is a result of my involvement in the research project Selfiecity (2013-2014), based on the analysis of 3,200 selfies shared on Instagram from five global cities: Bangkok, Berlin, Moscow, New York, and Sao Paulo. This research project was conducted by Software Studies Initiative, a research lab led by Dr. Lev Manovich and based in the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. In this research project, the lab used computational and data visualization methods to analyze large numbers of photographs shared on Instagram. In this article, I situate the selfie in the context of history of photography and seek to inscribe this sub-genre in a broader genealogy of photographic self-portraiture.