"Fifty Year Eclipse: Illuminating the Forgotten Legacy of Photographer Vilis Rīdzenieks" inVilis Rīdzenieks. Edited by Katrīna Teivāne-Korpa. Riga: Neputns, 2018.

Read moreSeeing a Century Through the Lens of Sovetskoe Foto

Published in Moscow, Russia, from 1926 to 1991, Sovetskoe Foto (Soviet Photography) was the only specialized photography magazine in the Soviet Union, aimed at a broad audience of professional photojournalists and amateur photographers. As such, it is unequaled in representing the official photographic culture of the USSR throughout the history of this country. In this article, researchers at the Cultural Analytics Lab explore the digital archive of Sovetskoe Foto to find out what it can tell us about the history of this remarkable magazine and the twentieth-century photography in general.

Read moreMapping the Universe of Instagram Photography (New York, 2018)

"The Networked Camera: Mapping the Universe of Instagram Photography" is a talk I presented at the panel Social Media in Theory & Praxis: What Is at Stake Now? at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, April 18, 2018. The event was a presentation and panel discussion featuring five invited speakers, organized by The Graduate Center Program Social Media Fellows.

The organizers: "Use of digital platforms and tools like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, and Google has altered cultural production, political processes, economic activity, and individual habits. This event is a presentation and panel discussion on several pressing issues in social media and digital literacy featuring five invited scholars, organized and moderated by The Graduate Center Program Social Media Fellows. The speakers bring expertise in a range of timely topics including: grassroots use of the Internet, feminism, free and open source project development, labor, appropriation, peer production, virtuality, networked cameras, and big cultural data analysis."

One of the most interesting social media—Instagram—is photography-based. It presents questions such as: how we can discuss it as a new chapter in the timeline of the history of photography, and as an important contribution to the contemporary visual culture? These questions have been at the center of the recent research at the Cultural Analytics Lab, a research lab based at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, and led by Lev Manovich, a leading culture and media theorist and Professor at the Computer Science department. The work of the lab combines the latest methods of computer science and the humanities. In the talk, I presented some of my research that I've done since 2013 while I've been a research fellow at the Lab.

Summary of my talk:

Instagram—an online platform designed for sharing photographs taken with a smartphone—exemplifies what philosopher Vilém Flusser calls “the universe of technical images.” The main question that I will address today is—how to study this universe?

First, in order to fully grasp the visual culture that has emerged in the universe of Instagram since its first release in October 2010, we need to unpack the work of the networked camera. It is not just a new kind of camera. The networked camera is a hybrid tool that seamlessly merges making, editing, sharing, and viewing of images. It comprises hardware and software, the availability of wireless Internet connection, and the existence of online image-sharing platforms such as Instagram. It produces not only images, but also layers of metadata, and establishes connections and relationships. The networked camera has created new conditions for making and viewing photography, and our task is to come up with new methods of studying it.

Instagram is a product of the networked camera, this hybrid device, where making and sharing of images is inseparable from their viewing. All stages of photographic production, distribution, and reception take place seamlessly within the same user interface. Which is significantly different from all earlier photographic practices where these three stages were distinct and separate.

From an art-historical perspective, there is no such thing as Instagram. Because each user’s experience of Instagram photography is unique— every person’s Instagram feed is different. The live feed of images consists of contributions by those other Instagram users that this person is following. If we want to consider the ways in which regular Instagram users produce and consume photography within this platform, we, art historians, are left quite confused. We cannot study Instagram photography the same way we are trained to study, let’s say, photographs exhibited in museums and galleries, kept in archives and personal albums, or reproduced in photo-books and magazines.

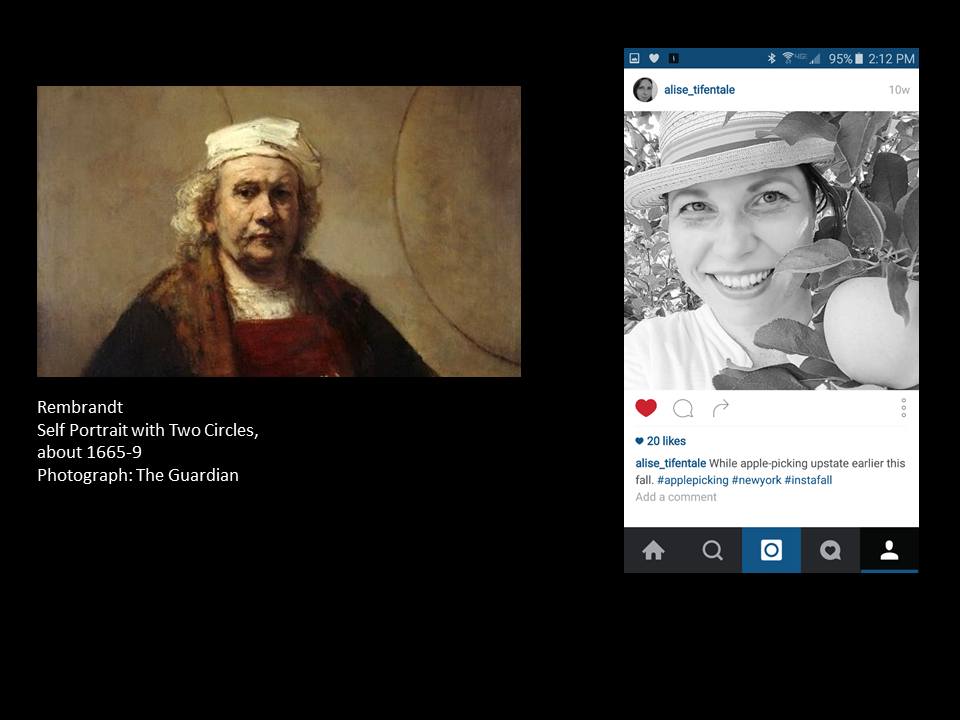

One thing that we can do, however, is to study a selected group of photographs. For example, I’d like to mention the notorious subgenre of popular photography, the selfie. We have studied it extensively at the Cultural Analytics Lab, since the launch of the project called Selfiecity. Since its emergence in 2013, however, the selfie has become one of the most attacked and misunderstood image types produced by the networked camera. Selfies on Instagram have been criticized, among else, as miserably failing successors to the painted self-portraits of the Renaissance and Baroque artists. Such comparisons, however, ignore the historical and cultural specificity of each case.

The approach to study a selected group of photographs such as selfies can be productive, but it is also dangerous because it deliberately extracts some photographs from their natural environment—it isolates these images from the networked camera, from this hybrid device of their making, editing, sharing, and viewing. And that can be misleading. Instagram photographs are not floating in some kind of vague space. They are not directly comparable to paintings, or even photographic prints. They have their own, very specific materiality because they are inseparable from the networked camera.

Individuals are using the platform of Instagram to create their galleries, and they are conveying all kinds of messages in the language of photography. One might ask—but are these messages important? The universe of Instagram photography equally embraces professional and amateur photographers, it is equally open to famous artists as it is to self-taught activists, it hosts sophisticated and highly designed galleries as well as collections of family snapshots, it is used by reality TV stars as well as small grassroots communities. This universe unites multiple aesthetic sensibilities and numerous social uses of photography. As such, Instagram offers a perfect sample of contemporary photography-based, global visual culture.

But it is not easy to define. It is not an exhibition, it is not an archive, it is not a group of like-minded avant-garde artists, it is not a photographers’ agency or a magazine. Instagram photography seems to be quite different from all that art and photography historians have been studying so far. One tool that can be extremely helpful is what Lev Manovich in his book Instagram and the Contemporary Image calls Instagramism—a term that describes the ways in which Instagram photographs “establish and perform cultural identities.” Manovich writes:

“Instagramism is the style of global design class, although it is also used by millions of young people who are not professional photographers, designers, editors, etc. This global class is defined not by the economic relations to the “means of production” or income, but by Adobe Creative Suite software it uses. It is also defined by its visual voice, which is about subtle differences, the power of empty space, visual intelligence, and visual pleasure.”

This Instagramism is not yet as familiar and as heavily theorized than all the other -isms we know all too well—such as Realism, Surrealism, Cubism, and so on. To fully understand Instagramism requires to construct your own set of critical tools that departs from what we take for granted.

The Graduate Center, City University of New York. April 18, 2018.

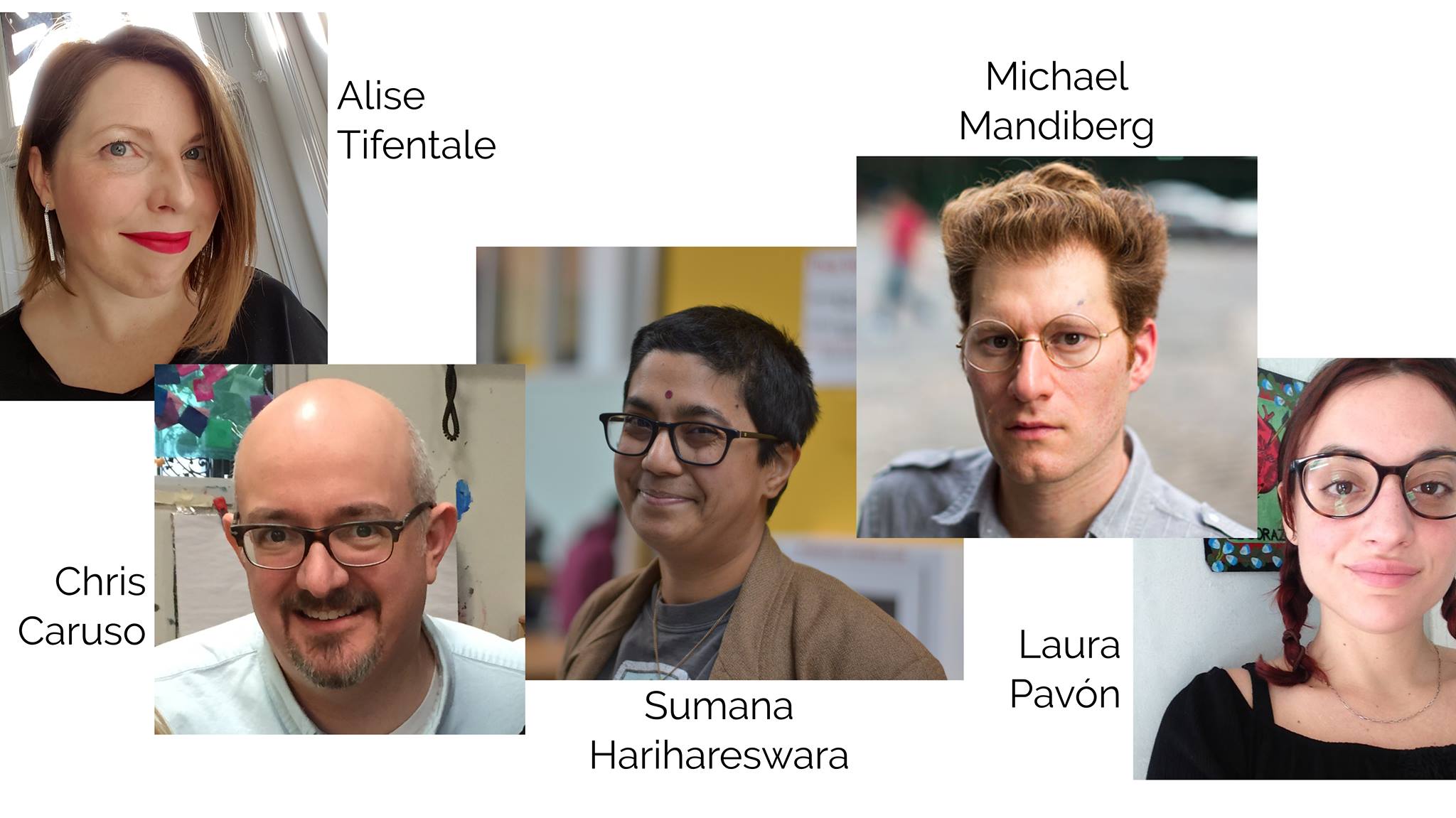

List of all speakers at the panel (listed alphabetically):

Chris Caruso, PhD candidate in CUNY Graduate Center Anthropology. Interests: poverty, social movements, political economy, and grassroots use of the Internet.

Sumana Harihareswara, Founder and Principal of Changeset Consulting. Interests: feminism, open culture projects, free and open source software development, and project management.

Michael Mandiberg, Professor of Media Culture (CSI) & Coordinator of the ITP Certificate Program (GC). Interests: interdisciplinary+conceptual art, appropriation, the digital vernacular, and peer production.

Laura Pavón, PhD candidate in Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures (GC). Interests: Twitter and virtuality, narratives of Mexicanidad+Latinidad, affect theories, and gender studies.

Alise Tifentale, PhD candidate in Art History, The Graduate Center, CUNY. Interests: Instagram and identity, networked cameras, visual culture, and data science+big cultural data.

Moderators: Jennifer Stoops (Urban Education) and Naomi Barrettara (Music).

The Graduate Center, City University of New York. April 18, 2018.

The Family of Man and the Family of Photographers (Riga, 2018)

"The Family of Man (1955) and the Family of Photographers: Insiders and Outsiders of the Most Famous Photography Exhibition" is a talk I presented at an international symposium "Now Memories" as part of the Riga Photography Biennial 2018 programming. The symposium took place on April 13 and 14, 2018, in Riga, Latvia.

For inviting me to speak at this symposium, I am grateful to Indrek Grigor, the symposium's curator. He also kindly accommodated my delivery of the talk as a video, pre-recorded in New York, and facilitated the very exciting live discussion with the audience after the talk via Skype.

The symposium was part of the larger program of cultural events Latvia 100 marking the centenary of Latvia's independence. Read more about this program here.

Curator Indrek Grigor (to the left) introducing my talk. Symposium "Now Memories," part of the program of the Riga Photography Biennial 2018. April 13, 2018. Photo: Kristine Madjare. #rigaphotographybiennial2018 #LV100

The abstract of my talk:

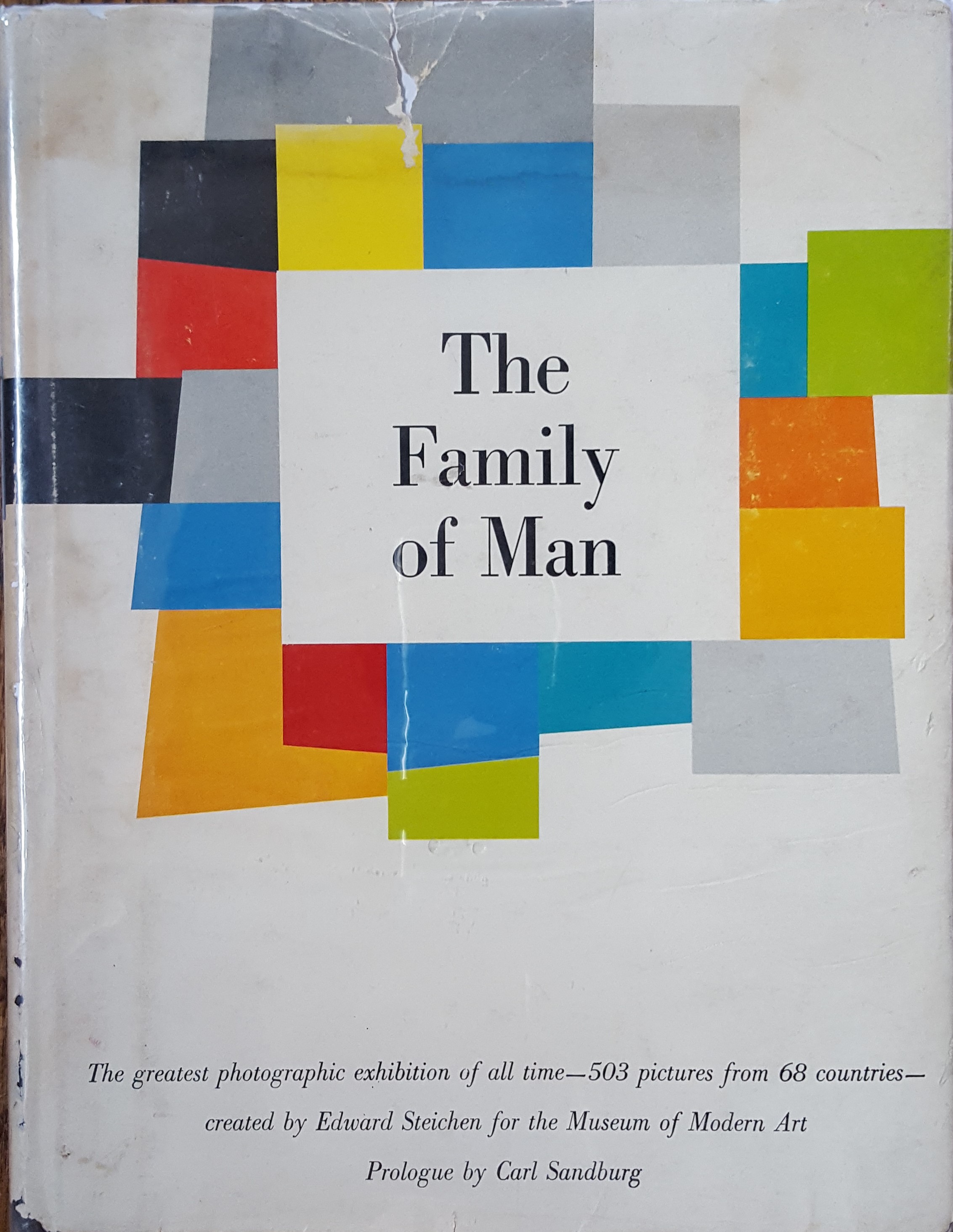

“The greatest photographic exhibition of all time—503 pictures from 68 countries—created by Edward Steichen for the Museum of Modern Art,” says the cover of the photo-book accompanying exhibition The Family of Man. The exhibition took place at the Museum of Modern art (MoMA), New York, from January 24 to May 8, 1955. It gained its central role in the twentieth-century photography history largely because of its international exposure. The U.S. Information Agency popularized The Family of Man as an achievement of American culture by presenting ten different versions of the show in 91 cities in 38 countries between 1955 and 1962, seen by estimated nine million people. The vast majority of the photographers whose work was included in this exhibition were based either in the U.S. or Western Europe. They had traveled to, and photographed in, numerous locations across the world. They were outsiders to the various cultures they encountered in Asia, Latin America, and Africa. Therefore, even with the best intentions, these Western photographers often reproduced the worst cultural stereotypes of the colonial era.

Around the time of the world tour of The Family of Man, however, there was another organized attempt to bring to light work made by a more inclusive transnational group of photographers. It was the international biennial of photography, organized by the International Federation of Photographic Art.

The biennial, established in 1950, was conceived as a world survey of contemporary photography, displaying an equal number of works from each of the fifty-five participating countries. This biennial functioned as a complete antithesis to The Family of Man—there was no U.S. participation in the biennial, and most images were authored by photographers who lived in Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe. Unlike the globe-trotting Western journalists whose work comprised The Family of Man, this biennial highlighted those photographers who were insiders to the multiple non-Western cultures of the world—they actually lived and worked in places which the traveling outsiders had briefly visited.

In this talk, I will discuss the two radically different approaches to organizing photography exhibitions, exemplified by The Family of Man and the biennials of the International Federation of Photographic Art. I will address the political agendas behind them as well as the social and economic context. Most importantly, I will answer the question, why photography scholars continue to debate The Family of Man today, while the biennials have been virtually erased from the mainstream history of photography.

About

Education, Research, Curating, and Teaching

Read moreContact and Connect

Contact and Connect

Read moreJosé Oiticica Filho and His Role in Defining Postwar Photographic Art (São Paulo, 2017)

I had the honor to present my research about the Brazilian photographer José Oiticica Filho (Rio de Janeiro, 1906–1964), a key figure of Brazilian modernist photography who made a global impact on the understanding of photographic art in the 1950s. I contributed to a conference dedicated to studying his oeuvre.

The conference took place on August 22, 2017, and coincided with an exhibition of his work in Galeria MaPA, São Paulo, Brazil, July 11 - August 31, 2017.

I was invited by art historian and curator Marly Porto.

Watch the video recording of my talk on the Galeria MaPa Facebook page:

My current research deals with the ways how the idea of photographic art was defined and negotiated on a global level after the Second World War. During the 1950s, photographers throughout the world were struggling for the recognition of their creativity and the artistic potential of photography. The works by Brazilian photographers and especially José Oiticica Filho were extremely visible and important in this struggle.

One of the publications which documents the global scope of this struggle is the Yearbooks by the International Federation of Photographic Art (FIAP). These Yearbooks showcase photographic art from more than 50 countries. They include works by Oiticica Filho as well as many other members of the Foto Cine Clube Bandeirante.

Spread from the 1960 FIAP Yearbook (with works from the 1958 FIAP Biennial). Left: José Oiticica Filho (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), Abstraction. Right: José V. E. Yalenti (São Paulo, Brazil), Architecture.

Oiticica Filho's work is central to my research because he introduced radical, non-representational work into the field of postwar photographic art which consisted mostly of two other types of photography - one of them based on pictorialist aesthetics, the other - on documentary, humanist photography. Oiticica Filho’s approach was radically different. His work was asserting that photography can be an art form, and that this art form is free from the task to depict anything from the visible reality. Instead, it creates a reality of its own. His work is a bold statement of photography’s artistic independence. No doubt his work served as an inspiration for many postwar photographers who were exploring the creative possibilities of photography.

The attention Oiticica Filho's work is receiving recently is long overdue, and I am especially thrilled to be part of the movement among art and photography historians that is concerned with revisiting the postwar histories and looking beyond the usual shortlist of famous photographers from France, Germany, and the U.S.

It is also remarkable that the conference on José Oiticica Filho in São Paulo coincided with the first major museum retrospective of the work by one of his sons, Hélio Oiticica (1937–1980), To Organize Delirium in the Whitney Museum in New York (July 14 - October 1, 2017).

Read the essay (in Portuguese) about José Oiticica Filho by Marly Porto-download the pdf here.

View selected works by José Oiticica Filho on the web site of Galeria MaPA:

¿Qué separa a los fotógrafos de los artistas? My article translated into Spanish

"¿Qué separa a los fotógrafos de los artistas?" is my article "Into the Photographers’ Universe: What Separates Photographers from Artists?" translated into Spanish and published in October 18, 2017 edition of MALBA Diario, online magazine of the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires(MALBA), Argentina.

Read moreThe Past is Present: Time and Space in Māra Brašmane’s Photographs of the Riga Central Market

The Riga Central Market is a landmark structure in the center of Riga, capital city of Latvia. It was built in the 1930s. Renowned Latvian photographer Māra Brašmane has observed everyday life in this market in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and into the 2000s and 2010s. Through the changes in the marketplace you can notice the changes that Latvian society underwent in these decades.

Read moreThe Family of Man: The Photography Exhibition that Everybody Loves to Hate

“The greatest photographic exhibition of all time—503 pictures from 68 countries—created by Edward Steichen for the Museum of Modern Art,” says the cover of the photo-book accompanying exhibition The Family of Man. The exhibition took place at the Museum of Modern art (MoMA), New York, from January 24 to May 8, 1955. It was highly popular—the press claimed that more than a quarter of million people saw it in New York. But it gained its central role in the twentieth century photography history largely because of its international exposure. The U.S. Information Agency popularized The Family of Man as an achievement of American culture by presenting ten different versions of the show in 91 cities in 38 countries between 1955 and 1962, seen by estimated nine million people But, contrary to the popular reception, scholarly criticism of the exhibition was—and continues to be—scathing.

Read moreFIAP Biennial in Photokina 1956: A Revolt Against the Universal Language of Photography

"FIAP Biennial in Photokina 1956: A Revolt Against the Universal Language of Photography,” The Notebook for Art, Theory and Related Zones 26 (2019): 120-146.

Read moreThe Myth of Straight Photography: Sharp Focus as a Universal Language

That photography is a language, and a universal one at that, was a popular metaphor in the 1950s. Such a language, as photographers and politicians claimed, could finally unite all people of the world because it transcends languages, cultures, religions, political positions, and any other differences. Although today such a belief in the power of photography can seem naïve, in the decade following the end of the Second World War it expressed a hope for a better—peaceful—future. But not just any kind of photography was believed to be a universal language. When Rothstein and many others in the 1950s were talking about photography as a universal language, they arguably had “straight,” documentary photography on their mind. But exactly what kind of photography is “straight,” and why it was supposed to be so universal?

Read moreUnderexposed Photographers: Life Magazine and Photojournalists’ Social Status in the 1950s

Today, we are used to seeing documentary images by photographers such as Margaret Bourke-White, Henri Cartier-Bresson or Robert Doisneau as fine art prints in art museums and galleries. But most of these images were initially made for the magazine page where the photographer’s name often went unnoticed. The US-based illustrated weekly magazine Life was instrumental in the process of photographers gaining more recognition and global exposure. However, this process was neither smooth nor free of obstacles.

Read moreInto the Photographers’ Universe: What Separates Photographers from Artists?

This essay describes a global community of photographers, their constant struggle to be recognized as artists, and the constant failure of this struggle. In this essay, I introduce the term “photographers’ universe” to define the community of photographers. An abyss separates this photographers’ universe from the art world.

Read moreSão Paulo photographers in FIAP, 1950-1965

"São Paulo photographers in global context: Brazilian participation in the International Federation of Photographic Art, 1950–1965." Research paper presented at the conference In Black and White: Photography, Race, and the Modern Impulse in Brazil at Midcentury at The Graduate Center, City University of New York, May 3, 2017.

Read moreThe Misunderstood 'Universal Language' of Photography

"The Misunderstood 'Universal Language' of Photography: The Fourth FIAP Biennial, 1956." Paper presented at the conference Art, Institutions, and Internationalism: 1933–1966 in New York City, March 7, 2017.

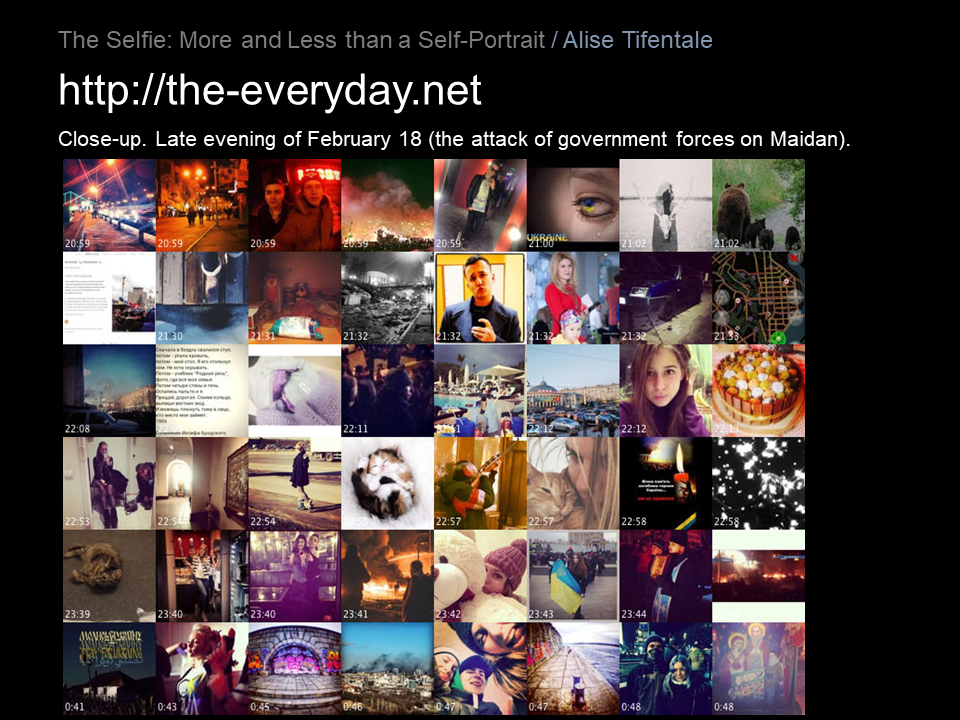

Read moreThe Selfie: More and Less than a Self-Portrait (New York, 2016)

"The Selfie: More and Less than a Self-Portrait," an invited talk at the symposium What Now? 2016: On Future Identities, organized by Art in General in collaboration with the Vera List Center for Art and Politics (May 20-21, 2016). New York City, May 21, 2016.

Download symposium booklet PDF and view the video recordings of all talks and panel discussions on Art in General web site here.

I am very grateful to Anne Barlow, director of Art in General, for inviting me to be part of this exciting symposium.

My talk was included in the panel "Technology and Presentations of the Self," excellently moderated by Soyoung Yoon. I had the pleasure to discuss my research with two inspiring co-panelists, Daniel Bejar and Sondra Perry. We were joined by Evan Malater.

I am thankful to Carin Kuoni, director of Vera List Center for Art and Politics, for co-organizing and hosting the symposium. I wish to thank also Kristen Chappa and Lindsey Berfond of Art in General for making this happen.

My talk was based on a critical revision of some of the methods and findings of my co-authored research projects on social media photography such as Selfiecity (2014), Selfiecity London (2015), and The Exceptional and the Everyday: 144 Hours in Kyiv (2014) as well as subsequent research articles written by me or co-written with Lev Manovich.

See a short summary of the talk on the news section of this web site.

For a theoretical background, see my article "The Networked Camera at Work: Why Every Self-portrait Is Not a Selfie, but Every Selfie is a Photograph" published in the catalog of the 2016 Riga Photography Biennial.

Excerpt of the talk:

Selfies belong to what Vilém Flusser calls the universe of technical images. As such, these images have functions and characteristics that are different from traditional images such as paintings or drawings.

According to Flusser, the traditional images were observations of objects, whereas the technical images always are computations of concepts.

It follows that the technical images are not reproductive but rather they are productive. In other words, technical images are not a mirror of reality, but rather a projection, a constructed and produced image.

Therefore we could say that selfies are tools of production or construction of a self, rather than a representation of a pre-existing self.

Then what do selfies mean?

But to ask, what any photograph - a technical image - means, “is an incorrectly formulated question,” Flusser wrote in his book Into the Universe of Technical Images. “Although they appear to do so, technical images don’t depict anything: they project something. To decode a technical image is not to decode what it shows but to read how it is programmed.”

And furthermore, “We must criticize technical images on the basis of their program. Criticism of technical image requires analysis of their trajectory and analysis of the intention behind it. This is because technical images don’t signify anything: they indicate a direction.”

I would argue that the direction that selfies indicate is more away from reflection of the self in an art-historical sense and more towards the interaction with the apparatus of image-making and image-sharing which includes not only the image, but also the devices and software.

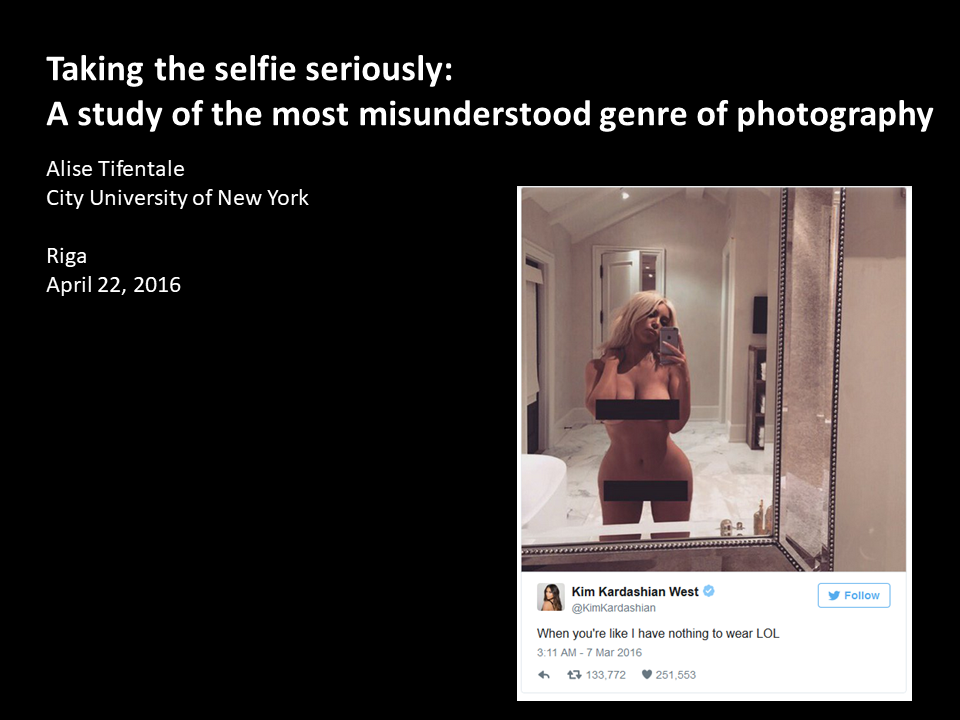

Taking the Selfie Seriously: A Study of the Most Misunderstood Genre of Photography (Riga, 2016)

"Taking the Selfie Seriously: A Study of the Most Misunderstood Genre of Photography," an invited talk at the Riga Photography Biennial symposium "Image and Photography in the Post-Digital Era" (April 22-23, 2016), Riga, Latvia, April 22, 2016. Symposium was organized by curator and art historian Maija Rudovska.

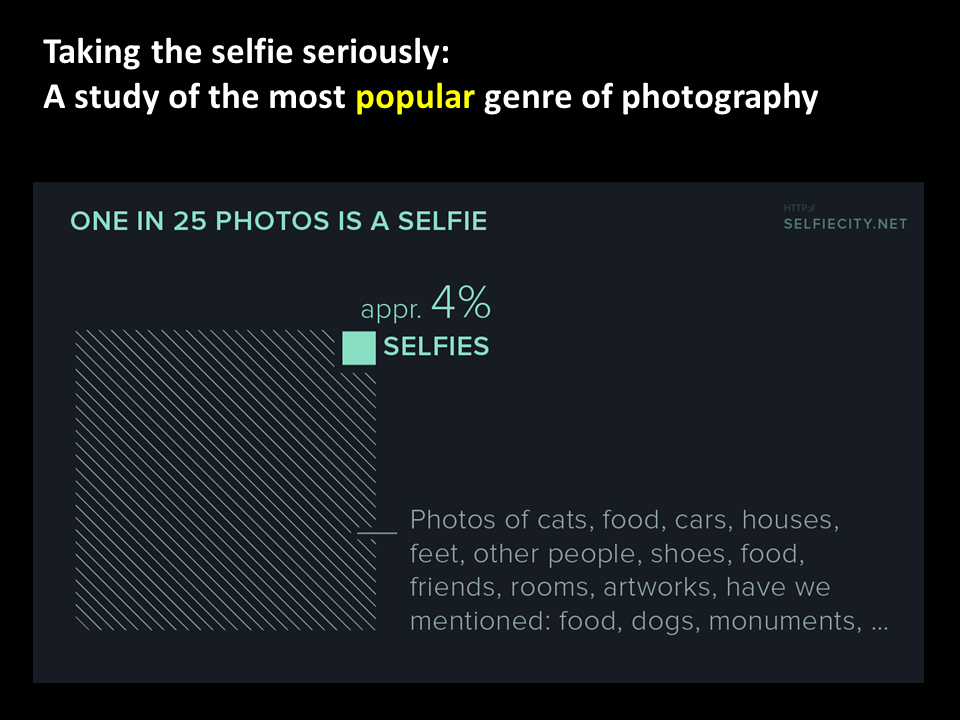

The talk was based on some of the methods and findings of the research project Selfiecity.net (2014) and subsequent research articles written by me or co-written with Lev Manovich.

For a further elaboration of the arguments proposed in the talk, see also my article "The Networked Camera at Work: Why Every Self-portrait Is Not a Selfie, but Every Selfie is a Photograph" published in the catalog of the Riga Photography Biennial.

The talk argued against the marginalization of the selfie as a notorious and outrageous kind of photography produced by reality TV stars and other celebrities as well as immature and psychologically unstable teenagers.

The findings of Selfiecity showed that some of the popular assumptions about the selfie are not true, and emphasized the diversity and cultural difference that can be communicated via this genre of popular photography.

Furthermore, the talk pointed to the two extremes of presentism in the popular discourse about the selfie: one describes this genre as something unprecedented and unique, whereas the other attempts to directly compare today's selfies to, for example, the painted self-portraits of the artists of the Renaissance. Both of these approaches lack methodological clarity and seem to overlook the historical specificity of the selfie and the particular cultural context in which this genre exists.

These popular misconceptions about the selfie at times make it complicated to view the selfie as just one of the many sub-genres of popular photography. This talk offered an alternative approach and discussed the benefits and limitations of combining computational analysis with humanities methods in order to make sense of the selfie.

Art and Communism: A Love-Hate Relationship (New York, 2015)

"Art and Communism: A Love-Hate Relationship," a guided tour in the exhibition Specters of Communism: Contemporary Russian Art, curated by Boris Groys (February 6 – March 28, 2015), at The James Gallery, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, New York. March 3, 2015.

People who have experienced communism tend to dislike it. People who have not experienced it tend to like it. This tour will trace the ‘specter’ of communism in the works on view, while also engaging in a broader discussion of the complex legacy of Karl Marx’s original observations about nineteenth-century Manchester. The spirit of communism was responsible for many contradictory events: it inspired the historical Russian avant-garde, supported the oppressive regime of Stalin, fascinated the students of Sorbonne in 1968, and supported Mao’s Cultural Revolution. Together we will practice Marxist dialectics in order to consider both sides of this ‘specter’.

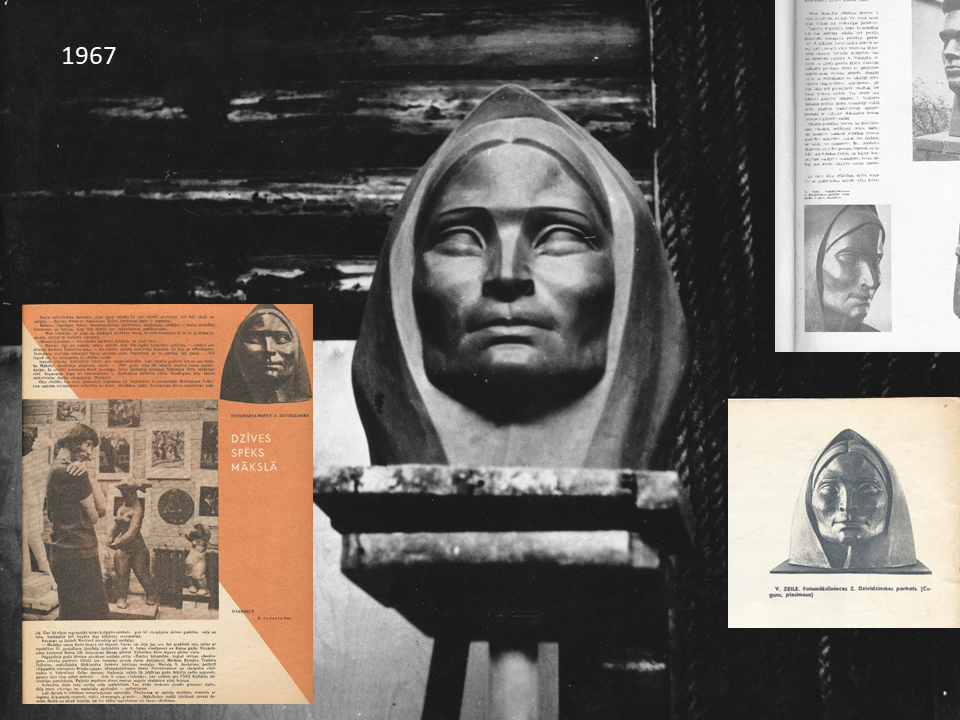

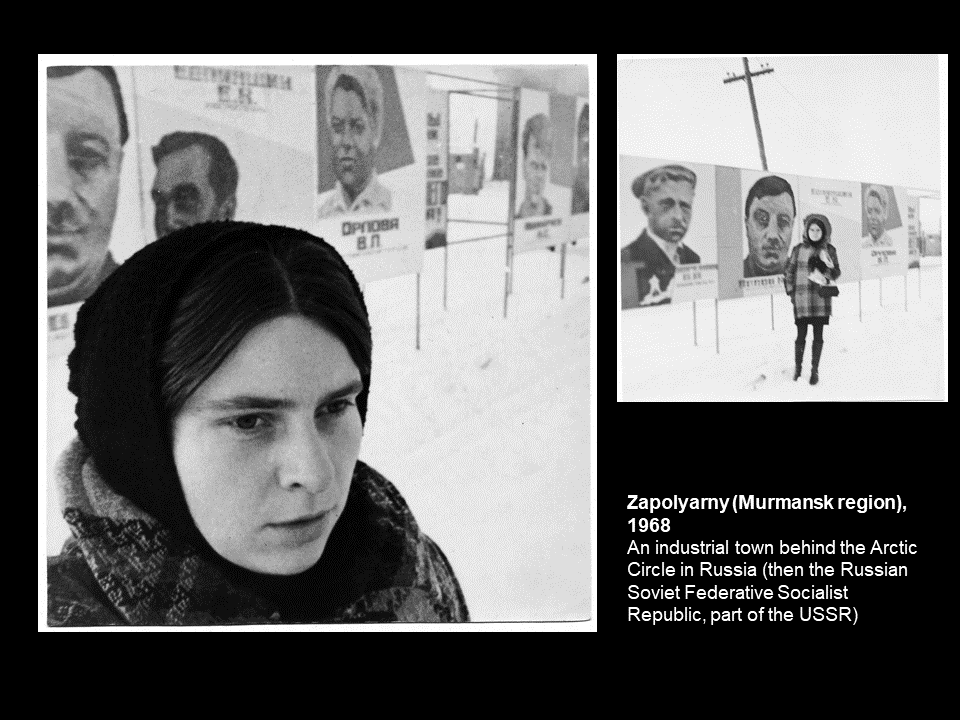

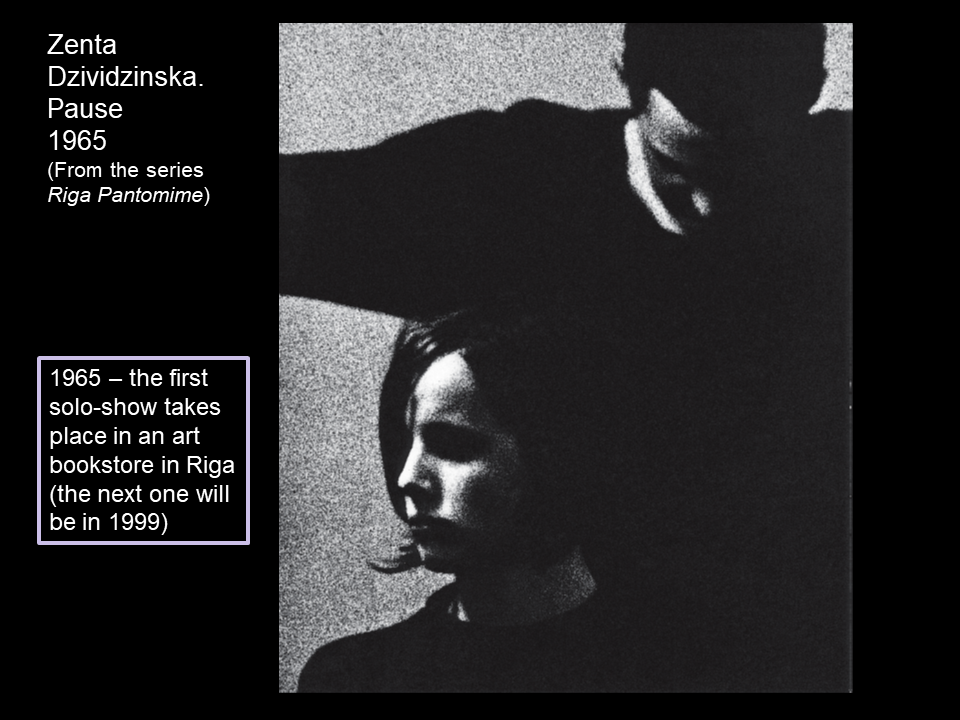

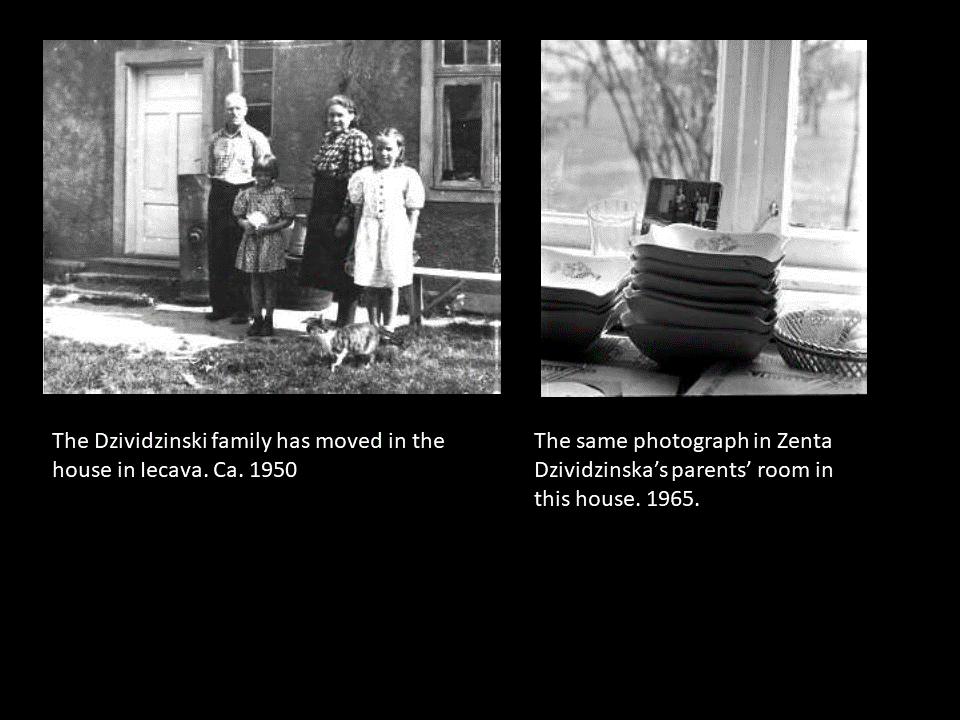

Avant-Garde in a Cottage Kitchen: Photographs by Zenta Dzividzinska from the 1960s (Malmö, 2014)

"Avant-Garde in a Cottage Kitchen: Photographs by Latvian artist Zenta Dzividzinska from the 1960s," The Moderna Museet, Malmö, Sweden, November 20, 2014.

Invited speaker on the occasion of a contemporary art exhibition Society Acts (September 20, 2014 - January 25, 2015), The Moderna Museet, Malmö, Sweden. Co-curator of the exhibition, Maija Rudovska, had included in the show a selection of photographs by Latvian artist Zenta Dzividzinska. My talk was aimed at introducing the Swedish public to the artist's oeuvre and the broader context of Latvian photography in the 1960s.

Read more about the exhibition concept on E-Flux.

The talk presents the extraordinary life and artistic career of Latvian artist Zenta Dzividzinska (1944-2011), focusing on her artistic output of the 1960s. Her choices were untypical and unconventional for the art world under the Soviets, and her works have remained relatively invisible even now. She chose photography as her major medium in time when photography was not considered a "real" art. Being almost the only woman in the competitive and patriarchal circle of unofficial art photographers in Riga, she succeeded in gaining their respect while still in her early twenties.

Alise Tifentale presenting the talk. Photo: hon Sun Lam.

However, her favorite subject - photographic depiction of everyday life in a country house featuring members of her extended family - was regarded as unsightly and ridiculous, thus most of her work has remained unpublished even now. That’s also where the cottage kitchen in the title of the talk comes from – that’s her parents’ little house in countryside, a village called Iecava in Southern part of Latvia. Even though she was educated in art school in the capital city Riga, and all the art world was happening in Riga, and all the jobs were there, most of the time Dzividzinska resided there and commuted to Riga. The small and cramped kitchen was a makeshift darkroom for her photographic work.

What understood meant by the word “avant-garde” in the title – in this case, I use the term to describe a radical practice, something that is ahead of time, a practice that is still to be understood by the public much later. Despite her being acknowledged as one of the leading fine art photographers in the late 1960s, during this decade Dzividzinska had only one solo-show – in 1965, in an art bookstore in Riga. Her next (and last) solo-show followed in 1999.